1961: The Fabulous Life and Loves of Clark Gable

The Fabulous Life and Loves of Clark Gable

by Maxine Block

Screenland magazine, March 1961

“We can say the King is dead but we can’t cry ‘Long Live The King’ because there is no one to take his place. And the belief is that no one ever will.” Charlton Heston for all of us spoke these words.

For three decades of movie-goers Clark Gable was not only the undisputed King of Hollywood but he also remained that rare combination—a man’s man and a lady’s man, both on and off the screen. He portrayed the hard-muscled, lusty, wise-cracking, masterful man of action. On screen and off, he was uncomfortable in a drawing room, more at ease as the kind of man with whom men could cast a fly in a mountain stream, draw a bead on a flying duck, empty a jug, play poker and use four-letter words. At the same time, to women, the pitcher-eared, six-footer with the natty mustache, quizzical expression and lopsided grin epitomized both brutal and tender masculinity. Even when wrinkles aged his face and crow’s feet etched his eyes, when his hair grayed at the temples, Gable had only to cock his eye at an actress, say “Okay, baby,” in that hoarse, organ-deep voice, and immediately every woman in the audience trembled with delicious anticipation.

For 30 years, come the depression, world war, cold war and television, Clark Gable remained the biggest movie box-office attraction of all time. An estimated two billion people saw his movies in every nation of the world where there are theatres. To the discrimination, some of his 65 pictures have been little short of terrible, but nothing could shake his popularity. He’d become an institution and a legend in his own time. As often happens with those who spend their days in the white heat of fame, the real Gable was lost in the glare. The myth of the tough, self-assured guy who could thrash the villain, resolve every situation with a flick of the hand and bring the heroine to his feet, took over. But it wasn’t Gable.

In reality, he was a self-conscious, basically insecure man who had few intimate friends and who was nervous in crowds. He stayed with one studio a record-breaking 24 years, afraid to strike out on his own, lived for the last 23 years in one house, married two women many years his senior, wooed a woman for many years who was five times a grandmother, only once fell in love with and married a young girl. The ruggedly handsome actor was a quiet, hard-working, publicity-shy guy who came on the set prepared—a business man who in an industry of wildly temperamental creatures, insisted on 9 to 5 hours, did his job and went home.

Once at a party, this reporter overheard a be-ruffled, middle-aged magazine writer coo, “Clark, how does it feel to be the screen’s Great Lover—the most desired man in Hollywood?” The screen’s Great Lover and most desired man squinted down at her to see if she was kidding. Then he flashed his famous grin, tinged with sheepishness, and observed laconically, “Well, it’s been a living.”

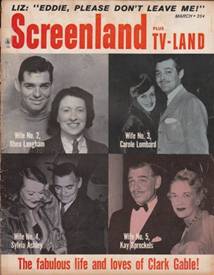

Though his personal romances were formidable in number, and he was five times married, Gable was uncomfortable in his public image as a mythical “he-man” cutting a swath through feminine hearts, swaggering through boudoirs like Don Juan. On screen he made females swoon in the days before anyone ever heard of bobby-soxers. Clark once said he had received some 5,000 marriage proposals by mail. “They almost always enclose a picture with their letters,” he explained, grinning self-consciously. “And let me tell you, the toughest job a man ever had is saying ‘no’—politely—to 5,000 women!”

The man who was a masculine symbol of supercharged virility to several generations of women reached beyond the grave to prevent the curious from turning his funeral into a circus such as occurred at Tyrone Power’s rites. “Clark told me many times of his fear that his funeral might become another macabre Hollywood spectacle and his body a freak for morbid strangers,” sobbed his widow Kay. “He wanted simple and dignified rites with the casket closed during the services and I followed his wishes.”

To Clark Gable’s shocked and grieving fans all over the world there was some consolation that their idol did not suffer during the only serious illness of his life—the heart attack which came in his 59th year. The unbearable sadness of his sudden death on November 16, 1960, is that he was facing the greatest happiness of his life in the baby Mrs. Gable is expecting next March, four months after Clark’s death. A half-year after Clark married Kay in 1955, she suffered a miscarriage. At that time he told a reporter: “You know what I regret most? I’ve been married five times and I have no family of my own. That’s sad. And now it looks like I never will.” To have a child of his own was the one thing denied the romantic star who had the world at his feet. As a final ironic twist, Clark will not be here to welcome his child just as dashing Ty Power was denied seeing his first son when death came to him also from a heart attack.

Clark was jubilant when he announced the expected child. In Reno, working on “The Misfits” with Marilyn Monroe, Clark told reporters: “When I wind up this picture I’m taking off until the baby is born. Isn’t that something—and me 59 years old! But then I always was a late starter. This is a dividend that has come to me late in life. I want to be free to enjoy my son.” (It never occurred to Gable that his firstborn would be anything but a boy.)

When Clark took for his fifth wife, the 37-year-old beautiful blonde actress, Kay William Spreckels, via the highly secret “standard Gable elopement”, he found at last the contentment and home life he has sought so long. She’d been married briefly to a college student, Parker Capps, and again briefly to an Argentine cattle heir, Martin de Alzaga, then to Adolph Spreckels, heir to a sugar fortune and by whom she had two children. The youngsters—Adolph (Bunker), 11, and Joan, 9—gave Gable a ready-made family. “It’s fun raising youngsters at this stage of life,” Gable once declared. “I’ve taught Bunker to ride and fish and I’m very fond of Joan who has her mother’s blonde beauty. I’ve always had a weakness for blondes.”

Clark had met Kay, a ravishingly lovely model, 14 years ago when he was recovering from the tragic death of his great love, Carole Lombard. Physically and in personality Kay bore a striking resemblance to Carole. She was sophisticated, witty, fun-loving and sports-loving. After they’d dated for a year, suddenly, without explanation, Gable terminated their friendship. It was whispered that Kay’s interest in marriage was too obvious to Gable. Hurt and humiliated, she put him out of her heart and mind and later married Spreckels. After Gable’s marriage and divorce from Lady Sylvia Ashley, he again sought out the fun-loving Kay who was estranged from her millionaire husband. At one point Kay and Gable’s friendship became a Hollywood sensation when Spreckels charged in a stormy temporary alimony suit that Gable had intimacies with Miss Williams. The actress denied the allegation and later she and Clark eloped.

“I am a very happy man,” Gable declared of his marriage. He considered Kay the wittiest woman he knew, laughed explosively at her humor and appreciated her social graces and intellect. When she developed heart trouble he cared for her tenderly and they were apart only when he joined his cronies for hunting in his Stockton, California, lodge.

The women in a man’s life help reveal what kind of a person he is. In Gable’s case they provide the real means of understanding this fabulous star—a man with a passion for privacy, one who turned the conversation away from his personal affairs. The big guy could have made a fortune from his autobiography but he never discussed the women in his life and remained to the end a gentleman who refused to kiss and tell.

In love, he was strange and unpredictable. His tremendous success gradually transformed him from the rough oil field hand to a polished “social” lion, fair game for husband-hunting actresses and socialites. But he shied off like a frightened rabbit when he was pursued too boldly. Strangely enough, Gable’s matrimonial record of five wives, like his many really bad pictures, was seldom criticized because of his friendly, honest manner and his healthy he-manliness. He never gained the reputation of such flamboyant contemporaries as Errol Flynn and Ty Power. Yet he had his share of quarrels with each wife expect Kay because of his roving eye and he traveled openly in Europe with assorted ladies between his marriages.

Clark Gable’s first marriage in 1924 to Josephine Dillon, now a frail 76-year-old drama coach who lives in a converted barn and ekes out a living on her old age pension and by teaching a few aspiring actors, was as strange a marriage as that of Marilyn Monroe and Arthur Miller. Why did a 23-year-old handsome and virile ex-old field roustabout marry a woman 18 years older than he, and later, when he was 30, marry a Texas socialite 11 years his elder? Though he was a man of legendary sex appeal and animal magnetism, the answer seems to lie in Gable’s early life. He never knew his mother, who died when he was a year old, and later, lost his stepmother in his early teens. It’s possible that he sought in these older women a security and comfort he had never known, a mother image and the stability of the permanent home he’d lacked in his formative years. In addition to this security, Josephine taught Clark the rudiments of acting, and his second wife, Rhea Langham, taught the former Ohio farm boy many of the social graces lacking in his poverty-stricken childhood.

For many years Clark was fascinated by older women of assured social position. He adored an undemanding, mature companion who had the gift of camaraderie, who was amusing, who liked to drink with him and stay up late and enjoy a bawdy story. But he could not abide the neurotic or possessive or demanding type. While Clark was still married to, but separated from, the motherly Rhea, he fell madly in love with youthful Carole Lombard. By then he was evidently secure enough to forsake his fatal preoccupation for women over 40 but later he returned to them. That was in 1935, though Carole and Clark didn’t marry until 1939 because of legal difficulties with Rhea.

Lusty, fun-loving and beautiful Carole Lombard seemed a perfect match for the quiet, introspective Gable. They’d first met at a party and quarreled; next day, she sent him a cage of doves. That became their way of settling arguments—many based on Carole’s jealousy. An extroverted glamour girl who liked parties and people, Carole drew him out of the shell of his self-conscious semi-seclusion during their brief marriage. Clark’s great love for his third wife overcame his own distaste at participating in the social life of the movie colony. Soon their raucous life together became a legend. To everyone in Hollywood Clark Gable was “The King” and the name clung.

Following Carole’s tragic death in an airplane crash in 1942, the film idol lived almost entirely in seclusion. He never quite got over the loss of Miss Lombard. They’d been pals as well as lovers—had gone hunting in Mexico and shot pheasant in South Dakota.

Many fans have expressed distaste over the fact that Gable was entombed next to Carole Lombard in Forest Lawn mausoleum and that his widow gave consent. But it was the movie idol’s desire and Kay merely followed his wishes. He’d bought the crypt adjoining Carole’s when he made her funeral arrangements. Seven months after her death Gable joined the Army as a private. He rose to the rank of major and flew many combat missions from bases in England.

After the war, The King resumed his social life, sometimes with mature society figures like Dolly O’Brien, grandmother to five, and wealthy Millicent Rogers, sometimes with glamour girls like Kay Williams, Paulette Goddard, Virginia Grey, Anita Colby and Evelyn Keyes. In 1949 Gable took his fourth plunge in marriage (“I like marriage; it’s my way of life”)—a plunge that took his friends by surprise. He eloped with the thrice-wed Lady Sylvia Ashley who also bore a startling resemblance to Carole Lombard. Gable had unexpectedly popped the question at a party the night before the elopement. It proved to be a wrong impulse, a costly one, and led to his shortest and most unhappy marriage. Within a year he told her: “I wish to be free; I don’t want to be married to you or anyone else.” Sylvia had spent a fortune redecorating Clark’s ultra-masculine Encino ranch house, where he and Carole had lived so happily. Clark hated to see his money spent on feminine fripperies for he had inherited a streak of thriftiness from his Dutch ancestors. Nor could he bear Sylvia’s little lap dog and her chi-chi friends.

For a short time another beauteous blonde, Grace Kelly, and Gable made a handsome duo after they finished shooting “Mogambo” in Africa. They were together in London, they dined in Hollywood, she wept buckets of tears after one parting. But nothing came of it. The Hollywood grapevine rumored that the cool beauty was altar-minded and Gable wasn’t. Some years later still another blue-eyed blonde, Kay Williams Spreckels, played it cool and became Mrs. Gable Number Five.

Born February 1, 1901, at Cadiz, Ohio, William Clark Gable, a 12-pound baby, had been a rough and tumble oil field worker, hopped freight trains and spent nights in flea-bag hotels before he turned to acting and dropped the “William”. His father, William Gable, a Pennsylvania Dutchman, was a roustabout in the oil fields, his mother, the former Adeline Hershelman, a farm girl. When Clark was 15, he took a job in a rubber factory in Dayton, Ohio, and it was there he saw his first play. He was so stage-struck he quit his job to become an errand boy in the theatre, at no salary. He ate sparingly on the coins actors offered as tips, slept in the wings. When his stepmother died, Clark accompanies his dad to the Oklahoma oil fields.

The work was discouraging and back breaking—swinging a heavy sledge hammer, climbing rickety wooden towers in a driving wind, chopping wood to keep up steam in the boilers. “I worked like this seven days a week,” Gable once recalled. “Finally, I said to myself, ‘There must be a better way to earn a living,’ and two years later, in 1922, against my dad’s wishes, I found it.” The stage-struck lad landed a $10-a-week job with a touring theatre company, was stranded in Butte, Montana, on a sub-zero night, hopped a freight to Portland, Oregon, and found work as a telephone lineman. It was when he arrived to repair a wire in a little theatre that he met the stage director, Josephine Dillon.

They married in Los Angeles and the gawky, jug-eared six-footer, determined on a theatrical career, tried pictures but made no progress. He turned to local stock companies, even tackled Broadway with no success. Undiscouraged, Gable returned to Hollywood, was seen in a play by Lionel Barrymore who found him some movie bit parts. A director recommended Gable to Darryl Zanuck, then chief of Warner Brothers.

Today Zanuck ruefully remembers: “I took one look at him, liked his engaging but self-conscious smile and told him: ‘Buddy, your ears are too big. You’ll never make it as a leading man.’” The depression ended the reign of the pomade pretty-boy movie lovers and crowned flop-eared, brawny Clark Gable king of the he-man era.

For Gable it all started with a slap in the face. Norma Shearer’s face, that is. The script of “A Free Soul”, filmed in 1930, called for Gable, as a gangster, in a bit part, to slap the heroine and shove her into a chair. Louis B. Mayer, Metro head, fearing women would be repulsed by the scene, decided to cut it after the preview. Other executives talked him into keeping it.

Nationally, the reaction was astounding. Thousands of women sent letters to the studio. All of them wanted to be slapped by Clark Gable. After that he played an auto racer, cowboy, test pilot, globe trotter, big game hunter, soldier, sailor, air force colonel, cavalry scout, pirate, gun smuggler, oil well wildcatter, war correspondent, secret service agent, gambler, financier, international adventurer—well, you name it, Gable played it. Though many of his films have been forgotten, an impressive number of them are enshrined in the Hollywood history books—film classics like “Hell Divers”, “Mutiny on the Bounty”, “Call of the Wind”, “Red Dust”, “Men in White”, “Honky Tonk”, “Test Pilot”, “San Francisco”, “It Happened One Night” and “Gone with the Wind”, the all-time favorite which has grosses over $50,000,000.

When Margaret Mitchell wrote “Gone with the Wind” she had Clark Gable in mind in her creation of Rhett Butler. Everyone knew it but Gable. “I never could see myself in that part,” he once said. “It shot for eight months, but I don’t think I worked more than eight weeks. I even got married (to Carole Lombard) and had a honeymoon during the picture. There were whole stretches I wasn’t in. But when Rhett did make an appearance, I guess you can say, he made it count.” Clark’s portrayal of Rhett Butler was one of the most memorable in screen history even though it was not his favorite role.

The part he liked best was the wisecracking newspaperman in “It Happened One Night”. It won him an Oscar in 1934. Always a big-boy bashful, almost humble, when you brought up his career as an actor, Gable explained once, “Metro had me in a rut playing mostly heavies or brutes. I was having a beef with the studio in those days. I was sick—even went to a hospital with exhaustion—but they threatened me with a suspension. To get even, they exiled me via a loanout to Columbia. In those days Columbia was a little independent on Poverty Row—Siberia for me, so my bosses at MGM thought. But I knew they had guessed wrong as soon as I read the script. The picture was a big turning point in my career…gave me a chance to play comedy, and from then on I was never type cast.”

“I’m no actor and I never have been. What people see on the screen is the real me,” he continued disarmingly. “I’ve been asked about switching from star to director. Hell, I haven’t even learned how to act yet.”

As the last of the true superstars, the dashing celluloid figure of Clark Gable brings down the curtain on an era. He was to the American motion picture what Ernest Hemingway is to American literature. An exponent of the straight-from-the-shoulder school of acting, he was believable as the rugged, handsome hero who downed the “heavy” in a good brawl yet could be tender and convincing in a love scene. Although he was a thorough professional to the end, few critics have bothered to consider Gable an actor. He was simply, “a hero.” The new batch of “Method” actors who portray mixed-up, emotionally unstable weaklings, frequently belittled Gable’s acting ability and called him a “personality performer in unsophisticated Gable-tailored scripts.” But the ladies in the audience who sighed for and the men who admired his uncomplicated masculinity do not agree. They will long mourn The King.

His last film, “The Misfits”, may well stand as a worthy memorial to Clark Gable. Critics believe he gave his best performance in a strenuous picture in which he put up with outrageous delays by Marilyn Monroe, temperamental outbursts from Montgomery Clift and miserable working conditions in blistering heat and dust storms. At a projection room screening of the unfinished picture, Gable turned to Arthur Miller (who did the script) and said, “I haven’t seen myself in anything this good in 20 years.” At Gable’s funeral, Miller summed it all up: “Of all the actors I’ve known, he was the only real man I ever met—the finest and truest gentleman.”

One Comment

Artie Segers

I still watch Clark Gamble movies my most favorite one is & was gone in the wind I’m 62 yrs old & I have a fine respect for Mr Gamble I wish I had of had the opportunity to meet him in person God Bless his kids & the rest of the family etc.