{New Article} 1940: Joe Lucky

This 1940 article was in The Saturday Evening Post, whom I’m guessing paid their journalists per word because all their articles are so very bloated. This one is 5,838 words, but who’s counting. Me, the one who typed it, I am the one counting. Anyway.

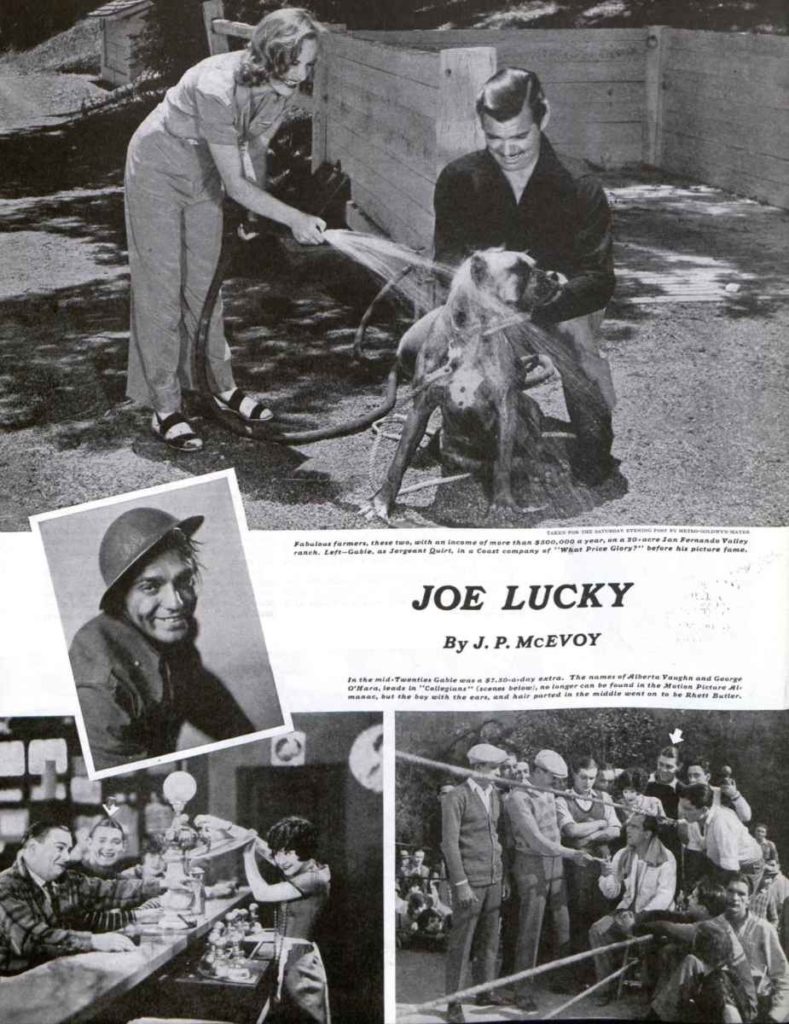

This article is supposed to be about how lucky Clark is and that’s why he is a success. But yet it goes into a rather pointless meandering tale of Clark’s early years working in the oil fields, the lumber camps, as a small time theatre actor–a lot of hard, broke times that eventually led to success. At least the author did indeed interview Clark, so you have quotes from him:

“[I] got a job in the lumber mill. I got a job piling green lumber. All the fellows worked by the foot. They worked hard. They made me work hard too. Probably the toughest work I ever did. The logs were rough, of course, and heavy, and I had no gloves. They all wore leather gloves or a leather palm. I’d tie onto that lumber and it was like grabbing hold of sandpaper. I used to soak my hands; they had cuts in them and would be all stiff and crack open. I’d soak ‘em in salt water and vinegar to toughen ‘em up. Alum, too, that was the stuff. I had hands like a prizefighter until I got my first paycheck and got my gloves, but I didn’t use ‘em before I got my hands all hardened up and toughened. After I’d been there about three months I forgot about the gloves.”

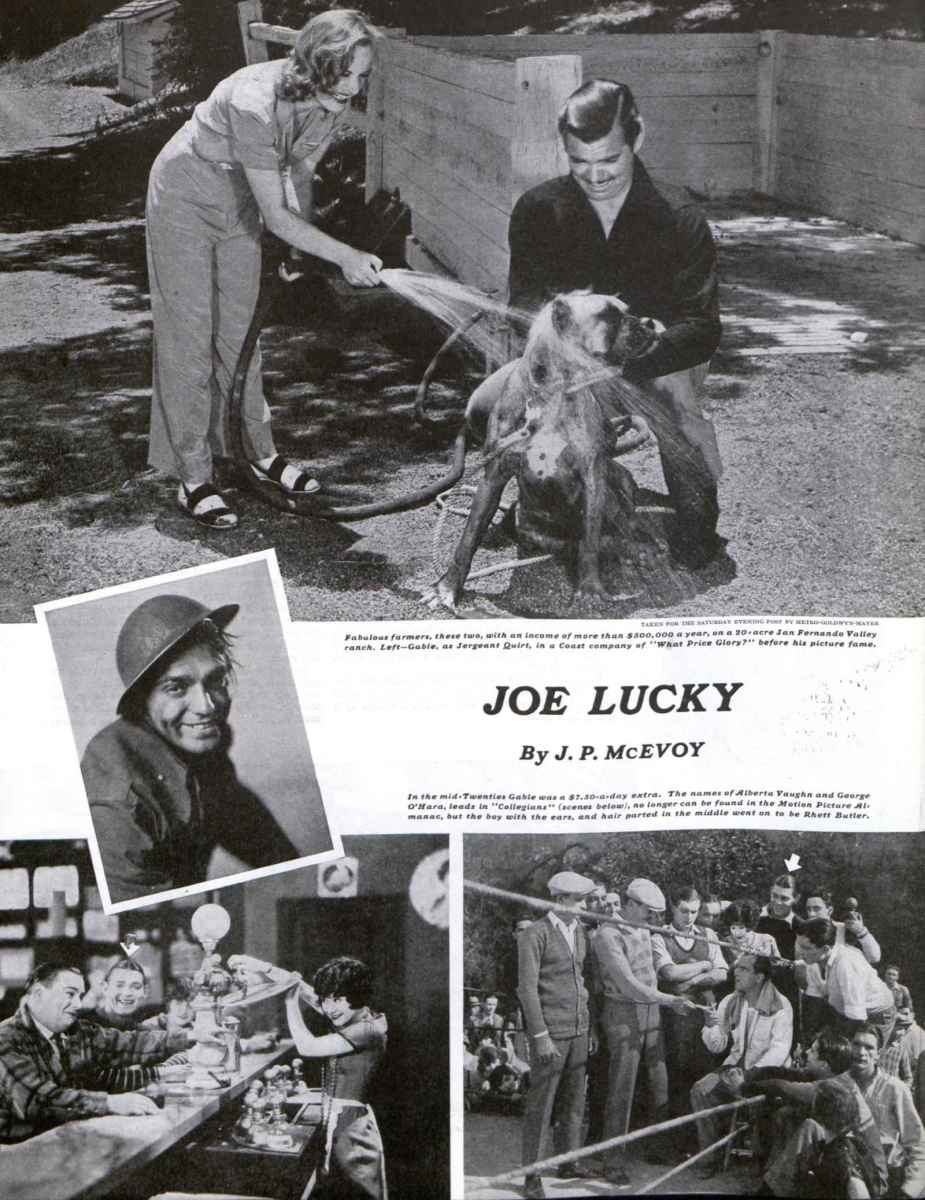

Most interesting part of the article to me is the author getting a tour of the Gables’ Encino ranch:

The ranch house, garages, stables and poultry coops are simple but expensively comfortable. The fruit trees are pruned, sprayed and massaged personally by Clark, who took me around and introduced me to each one separately, referring now and then to the tags identifying them, since all Clark’s farming experience was of the Ohio variety and how should he know from lemons, grapefruit and avocados?

“What do you do with the fruit?” I asked him.

“I give it away,” he said. “You can’t sell it, and even if I could, I wouldn’t get back anything like what it costs to raise. Why, when my farmer brought me the bill for irrigation last month I said to him, ‘What are you using on those orange trees—mineral water?’”

We walked around to the tool shed. Every known gadget for scientific farming was there, slick and shiny.

“This is my pet,” said Clark, and he patted an odd-looking contraption. “Whenever I have a spare moment, I come out and use this.” I wondered what it did. “It whitewashes,” said Clark. “It sprays whitewash on tree trunks, fence posts, anything you like. I’ve whitewashed everything around here but Carole.”

Back in the house we sat in the gun room and Clark rang for drinks. A man staggered in with two of the biggest Scotch highballs I’ve ever seen. “Have a little snort,” said Clark. “Carole will be down in a minute.”

We snorted and chatted. What were his plans for the future? “To keep going until they catch onto me.” How about knocking off sometime and doing a play? “Well, if I found one that was fun and didn’t show me up. I have no illusions about my acting.” Wasn’t he acting now, as Rhett Butler? “I have very little to do, as a matter of fact. Practically a stooge.” How did he happen to go in for farming instead of horse racing, like his neighbor, Bing Crosby, for example? “Because I farmed as a boy, I guess.” Did he like it then? “No. Hated it.”

“’The typical successful American businessman,’ said the late Don Marquis, ‘was born in the country, where he worked like hell so he could live in the city, where he worked like hell so he could live in the country.’”

“That’s about the size of it,” said Clark. “Silly, isn’t it? Except for an occasional hunting or fishing trip, I spend all my time out here. And yet, as much as I enjoy this place, the farmer who works for me gets more good out of it.”

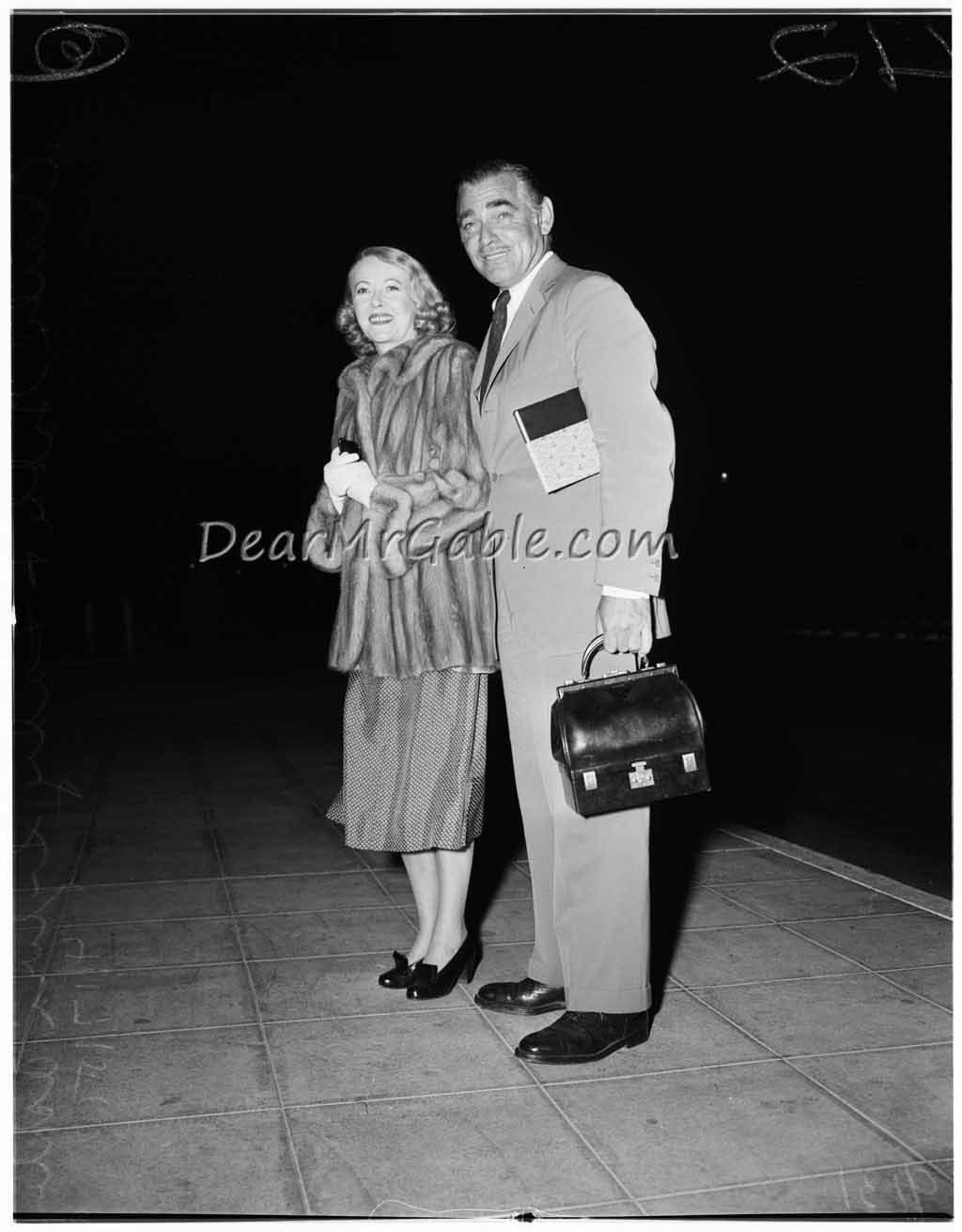

Fabulous farmers, these two—Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, with a total income of more than half a million a year and nothing to do with it but support a small citrus grove with what’s left after Uncle Whiskers takes 60 or 70 percent of it. Entertain? Not in the legendary Hollywood manner. A few intimate friends at home, yes; but the night clubs never see them. What does Clark do with his money? Well, he’s Dutch and thrifty and doesn’t need an elephant’s memory to recall how it feels to be broke and hungry, so he chances are very good that he goes down a hole with it every week, like a chipmunk. It takes a special kind of vigilance, anyway, to hold onto movie money, for it is a kind of cheese which a thousand varieties of Hollywood mice are always nibbling at. The agent takes the first good bite—10 percent of the gross—in Clark’s case, a neat 750 bucks a week. Incidentally, it is interesting to note in this connection that Clark’s present agent, Phil Berg, bought his contract from another agent a few years ago for $15,000, or the equivalent of twenty weeks’ present take. For Gable makes as much in ten weeks as the President of the United States collects in a year, which is decidedly unfair, since Roosevelt is a much better actor. Unfortunately for FDR, he hasn’t got a Hollywood agent.

You can read the article in its entirety in The Article Archive.

One Comment

Dan

Such a pleasure to come here every week to see what you have on offer. This is a bright spot on my Fridays