1961: After Tragedy, A Rising Star (Part 3)

After Tragedy, A Rising Star

By Adela Rogers St. Johns

The Orlando Sentinel, January 8, 1961

When he came back from the war, things ganged up on The King. This led him into a way of life utterly foreign to the Clark Gable his friends had known and to his only miserable marriage—Lady Sylvia Ashley, who had married her title.

She was the daughter of a footman, had been a London showgirl, and was the widow of Douglas Fairbanks Sr.

In the first shock of wild grief after his wife Carole was killed in an airplane crash, Gable enlisted and went overseas. While he was away fighting he was, as all the men around him were, separated from the women he loved.

He once told me that he used to forget that Carole was dead, he couldn’t believe she wouldn’t be waiting for him when he got back.

But—she wasn’t. He came back to the first cold realization of his loss.

Work is every man’s greatest panacea and right then for quite a while Gable had none. After Gone with the Wind, its producer, David Selznick didn’t make a picture for years. With what could you follow that epic of the Civil War? In a measure, Gable had that same problem.

To his horror he found that the top guys at the studio, even his old pal Eddie Mannix, wanted him to remain young. He himself had felt that first breath of autumn. He knew that middle-age was upon him. He was 43, and looked it.

He was grim, battered, all the boy gone, even the grin.

So for months after he got out of uniform, he couldn’t sink himself in the blessed forgetfulness of work. They did finally settle on a dilly—in exhaustion I always thought, because this tale had been bought for Freddy Bartholomew, rewritten first for Spencer Tracy and then for Mickey Rooney before Johnny Lee Mahin and Laurence Stallings tried to tailor it to Gable.

It was a dismal affair. Gable’s Back and Garson’s Got Him. It was as near a flop as Gable could have and he decided he was through as a movie star as well as a soldier. His work was gone as well as his wife. All he had left was money, and he couldn’t see anything he wanted to buy with it.

Fors the first time since he and little Franz Doerfer slept on the deck of that steamer crossing the Puget Sound, he was without a woman. Not only his heart and his house and his arms were empty; so was his daily life.

He quite literally didn’t know how to get through or arrange the hours.

All his social, practical life had been run in every detail. First Ria, in a beautiful house with exquisite order ad charm.

I remember being there one night with Frank Capra and his wife. When Clark came home and found we were all supposed to go out to a party he gave Ria the I-know-you’ve-been-in-the-house-all-day-but-I-don’t-want-to-go-out look, and Ria smiled and broke the date and miraculously a fine dinner appeared right there.

Among her other gifts, Carole had run the house always with a slap-dash we-love-you-all sort of hospitality that kept a light in the window and their friends running back and forth.

Now, everybody did their best but nobody knew just how. Gable was used to a wife, he couldn’t bear the thought of another woman in Carole’s place. So like a bear with a sore head, he retired into his cave to nurse his wounds.

I had a chance here. As his story representative at the studio, working with Mannix and Vic Fleming to get stories for him, I had to see him. I went to his house.

Driving over in the studio car, I had a feeling that Carole was shoving me.

I could almost hear that lovely husky laughing voice saying, “Look, chum, the only way to handle this big pig-headed Dutchman is to let him have it. Don’t let him get the bit in his teeth.”

He came out on the terrace wearing one of those white turtleneck sweaters he made famous when I saw how much weight he’d let himself put on. I said, to my own surprise, “I know a real fine story called Haunch, Paunch and Jowl. You’d certainly be perfect casting for the title role. That bourbon isn’t doing you any good.”

He glowered. Then he laughed. “On target,” he said, “I’ll start digging post holes in the morning.”

He did, too. But I knew he was drinking alone and that’s disaster for any man.

Sometime during that story discussion, I went to Carole’s room for a book. It’s not true that her dressing gown was still on the bed, her powder and perfume spilled on the dressing table. Gable had none of that morbid sentimentality.

The simple early American furniture and the chintzes were the same. Her books were where they’d always been. I got to looking at them.

I heard Gable coming up the stairs. He picked up a book of Eliot poetry, turning t in his big hands, staring down at the scrawled comments, the heavy underlining.

“She loved poetry,” he said, “ I don’t know much about it.”

“She loved God, too,” I said, indicating the crowded shelves.

“She wanted so much to find Him,” Clark said. “Then He hit her with a mountain. I don’t know anything about that any more either.”

“No, no,” I said, but I saw by his face he couldn’t talk about it yet.

We’d finished dinner when the phone rang. It was for me. The war was still on in the Pacific then. I listened, when I hung up and tried to put it back on the table, I missed. Clark picked it up and said, “Bad news?”

“My brother Thornwell has been killed with the marines,” I said, “his wife is at my house.”

Clark said, “I’ll take you home,” and I said, “Oh no, the car’s waiting,” but he said, “I’ll feel better if I drive you myself.”

Over the pass, he talked naturally about Thorny, whom he’d known as a young lawyer in Jerry Geisler’s office. At my house he gave me a pat on the back and I ran on in.

A couple of hours later my son Dick said, “Ma, do you want Mr. Gable to wait any longer? He’s still sitting out front in his car.”

I went out and Clark said gruffly, “Just want to tell you, be proud of him. Boy died for his country.”

“Yes,” I said, “so did Carole.”

The look he gave me was blazing honest. I thought he’d made it.

Then, unexpectedly, it seemed to his friends he went off the track altogether. He went to Hollywood parties of the type he and Carole had shunned.

Gable, who’d never gone to nightclubs, was seen in them, and he lost his temper at the studio. He couldn’t get up any steam for his work and from not good stories he made worse pictures.

For the only time in his career the clouds gathered about his fame and about him.

The charm society beauties had for him was that they were so different from Carole Lombard and the other hardworking, hard-playing women of the theater and the movies who earned their own living and saw life as a need to create, to work.

“You sure you want to go through with this?” Howard Strickling asked, when he’d been summoned by Lady Sylvia Ashley to arrange details of her marriage to Clark Gable.

“Of course he does,” Lady Sylvia said with her best British accent.

“I’m not asking you,” Howard said.

Gable said, “Might as well. Don’t worry, Howard.”

A week later he came out of whatever it was and faced his mistake. He’d have had more in common with an Eskimo. But it was his mistake, so he lived with it.

Then he began the long climb back to reality, to the man he had to be. Chagrined, unhappy, he had to prove himself worthy of the name they’d given him in love! The King. He’d never respected a king who could abdicate.

As a reward for this lonely effort, Kay Williams came back into his life once more. He’d survived the wrong woman so the powers that he sent him the right one with whom to live out his days.

She was a mature, experienced woman, with two small children, ready to take on being the wife of The King, which again as Carole used to say is quite a job. You have to put it first always, Carole said.

Now Kay could—and did. During those 10 years since they had met and separated they had both made unhappy marriages.

In all fairness to Lady Sylvia, perhaps she absorbed the shock of Gable finding he was married to and living with a blonde woman who wasn’t Carole.

Kay had married a millionaire, young Adolph Spreckels of San Francisco’s famous sugar-fortune first family.

They splashed their money and houses and quarrels and his jealousies across front pages until she left him.

Marriage to Clark Gable, now well past 50, a strong, lonely, determined man set in his ways was a specific job, like running a big business or overseeing a big research laboratory. I think she always knew that he could never love her with the abandon and glory he’d given Carole when they were in the prime of life together.

She loved him enough to devote her life to making him happy.

To Howard Strickling she said, “I will make him a home. I will learn to do whatever he wants me to do as a companion and to stay home when he doesn’t. This house he’s building in Palm Springs will be his house.

“My children are little, they are darlings, a boy and a girl. They need a father as badly as he needs a family. I will try to be to him what Carole would have bee now if she had lived.”

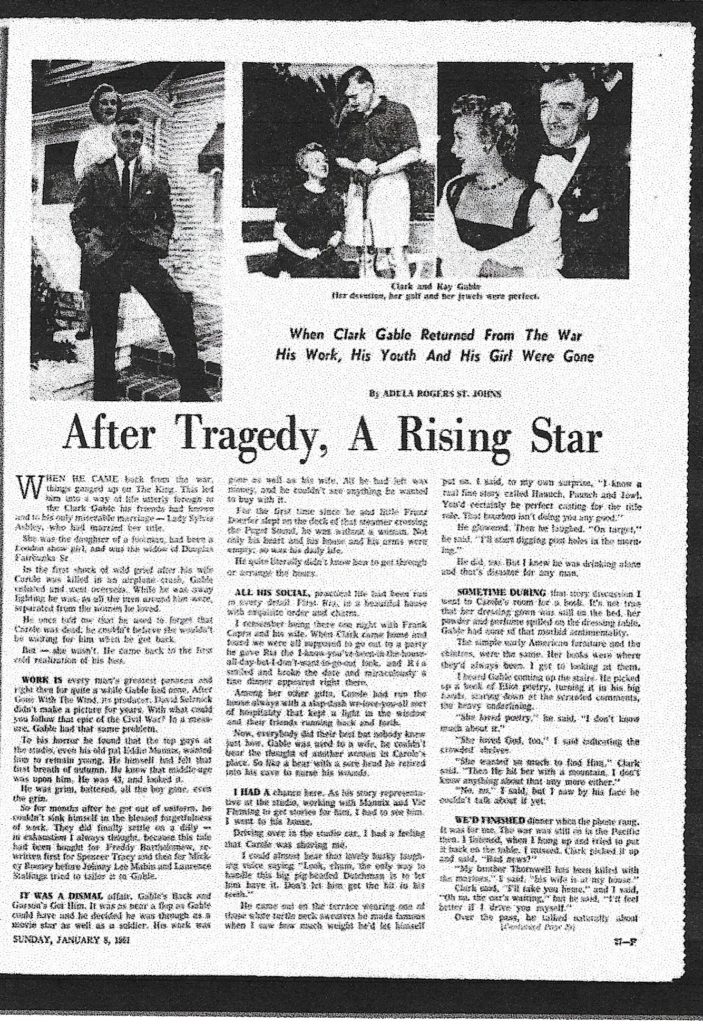

With care, constant thought, selfless devotion, Kay made Gable the perfect wife.

She learned to cook on the barbecue he had built at the Palm Springs house and the boys tell me nobody on earth can cook the things Clark liked best—beef stew, steak, roasted potatoes, corn, Spanish dishes—the way the beautiful Kay can cook ‘em.

Her golf score was exactly right when he wanted her to go around with him.

When they went out in public, she was the beauty, groomed, elegant, perfectly gowned, her jewels in exquisite taste. He liked a woman to be lovely when she appeared on his arm.

Above all, she did give him a family for the first time. Ria’s children had been almost grown up at the time of their marriage. He hadn’t been able to become pops to them as he did to Kay’s Joan and Bunkie who were 4 and 6.

Within a year the Gables were a family, at the desert house in Palm Springs, in the villa Kay set up when he made a picture in Italy where he took his kids to the historical sights and put them to bed every night.

Kay knew the movies, too. She was able to take part in the vital difficult changes in Gable’s career when after 23 years he left Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

In the ‘50’s, control of the motion pictures passed from the big studios to the independent producers and to the stars, taxes had made it necessary for them to own percentages of their pictures.

Catapulted by all this into a new career in a new art and industry, after a faltering start, Gable swept back to the top again. His popularity was reactivated as the younger generation saw The King, the magnificent Gable in his smash hit picture released to television.

Kay had succeeded 100 percent in her job.

The measure of her devotion is that he is buried now where he always felt he must be—wanted to be. Beside Carole.

But there is a place beside them for Kay. If this seems dramatic and unconventional, it is hardly reasonable to expect the king of the world of drama, the man millions loved for his outside personality to be bound by conventions.

Where there is no temptation, there isn’t perhaps a big virtue. If the measure of a man is in how he handles temptation, probably Gable had more than any other man I ever knew and he never fell for the bad ones.

Often I feel sorry for the young people who sometimes have to settle for the rat pack.

It’s really not so important that they called Gable The King.

What is important is that everyone who knew him from the US Army to the fan in the street, from the woman who loved him to the top brass and the grips and carpenters at the studio called him a man. That was a man. God bless him!

We shall not see his like again.