1961: Not One Job–But Many (Part 2)

Not One Job—But Many (Part 2)

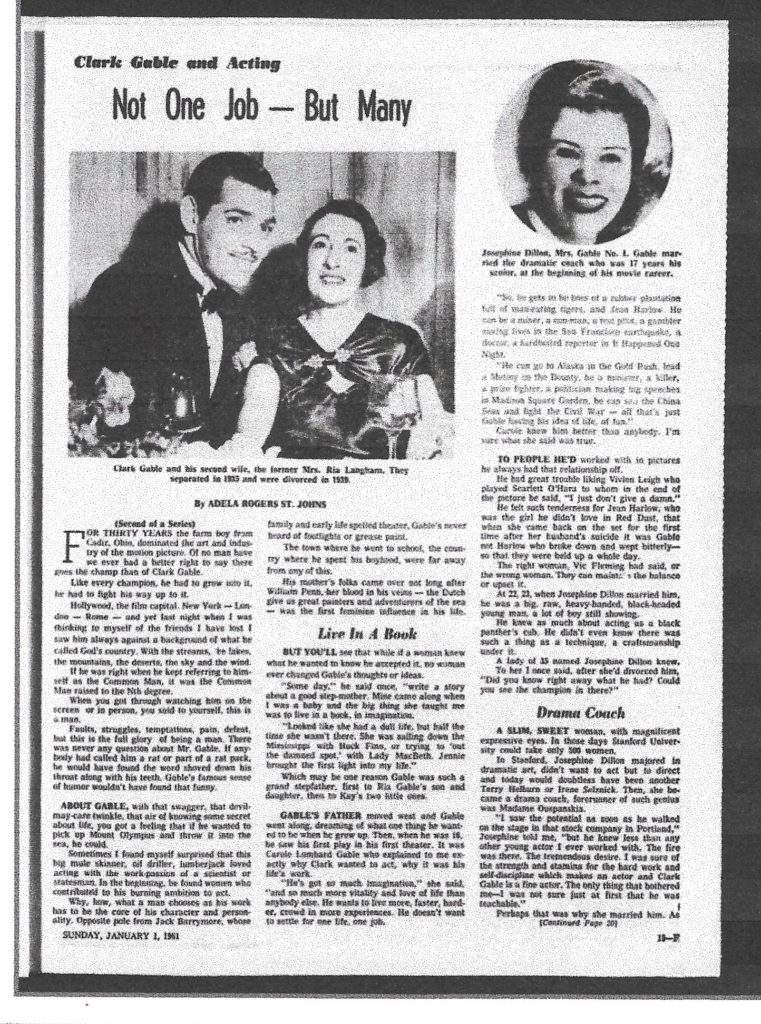

By Adela Rogers St. Johns

The Orlando Sentinel, January 1, 1961

For thirty years the farm boy from Cadiz, Ohio, dominated the art and industry of the motion picture. Of no man have we ever had a better right to say there goes the champ than of Clark Gable.

Like every champion, he had to grow into it, he had to fight his way up to it.

Hollywood, the film capital. New York—London—Rome—and yet last night when I was thinking to myself of the friends I have lost I saw him always against a background of what he called God’s country. With the streams, the lakes, the mountains, the deserts, the sky and the wind.

If he was right when he kept referring to himself as the Common Man, it was the Common Man raised to the Nth degree.

When you got through watching him on the screen or in person, you said to yourself, this is a man.

Faults, struggles, temptations, pain, defeat, but this is the full glory of being a man. There was never any question about Mr. Gable. If anybody had called him a rat or part of a rat pack, he would have found the word shoved down his throat with his teeth. Gable’s famous sense of humor wouldn’t have found that funny.

About Gable, with that swagger, that devil-may-care twinkle, that air of knowing some secret about life, you got a feeling that if he wanted to pick up Mount Olympus and throw it into the sea, he could.

Sometimes I found myself surprised that this big mule skinner, oil driller, lumberjack loved acting with work-passion of a scientist or statesman. In the beginning, he found women who contributed to his burning ambition to act.

Why, how, what a man chooses as his work has to be the core of his character and personality. Opposite pole from Jack Barrymore, whose family and early life spelled theater, Gable’s never heard of footlights or grease paint.

The town where he went to school, the country where he spent his boyhood, were far away from any of this.

His mother’s folks came over not long after William Penn, her blood in his veins—the Dutch give us great painters and adventurers of the sea—was the first feminine influence of his life.

Live In a Book

But you’ll see that while if a woman knew what he wanted to know he accepted it, no woman ever changed Gable’s thoughts or ideas.

“Some day,” he said once, “write a story about a good step-mother. Mine came along when I was a baby and the big thing she taught me was to live in a book, in imagination.

“Looked like she had a dull life, but half the time she wasn’t there. She was sailing down the Mississippi with Huck Finn, or trying to ‘out the damned spot,’ with Lady MacBeth. Jennie brought the first light into my life.”

Which may be one reason Gable was such a grand stepfather, first to Ria Gable’s son and daughter, then to Kay’s two little ones.

Gable’s father moved west and Gable went along, dreaming of what one thing he wanted to be when he grew up. Then, when he was 16, he saw his first play in his first theater. It was Carole Lombard Gable who explained to me exactly why Clark wanted to act, why it was his life’s work.

“He’s got so much imagination,” she said, “and so much more vitality and love of life than anybody else. He wants to live more, faster, harder, crowd in more experiences. He doesn’t want to settle for one life, one job.

“So, he gets to be boss of a rubber plantation full of man-eating tigers, and Jean Harlow. He can be a miner, a con-man, a test pilot, a gambler saving lives in the San Francisco earthquake, a doctor, a hardboiled reporter in IT HAPPENED ONE NIGHT.

“He can go to Alaska in the Gold Rush, lead a mutiny on the Bounty, be a minster, a killer, a prize fighter, a politician making big speeches in Madison Square Garden, he can sail the China Seas and fight the Civil War—all that’s just Gable having his idea of life, fun.”

Carole knew him better than anybody. I’m sure what she said was true.

To people he’d worked with in pictures he always had that relationship off.

He had great trouble liking Vivien Leigh who played Scarlett O’Hara to whom in the end of the picture he said, “I just don’t give a damn.”

He felt such tenderness for Jean Harlow, who was the girl he didn’t love in RED DUST, that when she came back on the set for the first time after her husband’s suicide it was Gable not Harlow who broke down and wept bitterly—so that they were held up a whole day.

The right woman, Vic Fleming had said, or the wrong woman. They can maintain the balance or upset it.

At 22, 23, when Josephine Dillon married him, he was a big, raw, heavy-handed, black-headed young man, a lot of boy still showing.

He knew as much about acting as a black panther’s cub. He didn’t even know there was such a thing as a technique, a craftsmanship under it.

A lady of 35 named Josephine Dillon knew. To her I once said, after she’d divorced him, “Did you know right away what he had? Could you see the champion in there?”

Drama Coach

A slim, sweet woman, with magnificent expressive eyes. In those days Stanford University could take only 500 women.

In Stanford, Josephine Dillon majored in dramatic art, didn’t want to act but to direct and today would doubtless have been another Terry Helburn or Irene Selznick. Then, she became a drama coach, forerunner of such genius was Madame Ouspanskia.

“I saw the potential as soon as he walked on the stage in that stock company in Portland,” Josephine told me, “but he knew less than any other actor I ever worked with. The fire was there. The tremendous desire. I was sure of the strength and stamina for the hard work and self-discipline which makes an actor and Clark Gable is a fine actor. The only thing that bothered me—I was not sure just at first that he was teachable.”

Perhaps that was why she married him. As his wife, living with him, being with him night and say, she could work with him with more closeness, more persuasion.

Of course, she was in love with him and he loved her, too. A starstruck boy, his whole heart turned to the work that came so slowly, where he was beginning to see how much there was to know and learn and how little of it he knew.

For four or five years, this elegant lady, this intellectual artistic highly educated woman, worked with the volcanic lava of Clark Gable as a sculptress might work with clay.

Then–suddenly—it was over. Had to be. The age difference caught up. With quiet dignity, she let him go. Friends? I don’t think so. Josephine Dillon Gable wanted acknowledgement of king-making. Yet to be the first wife and teacher of the man who became idol of all women and the greatest movie star of all time is still the glory of her life and work.

Ria Langham, the second Mrs. Gable, was something else. Like many Texas women, she kept the vitality of the West, added the worldly polish and glitter of New York.

Eleven years older, she fell in love with him across floodlights and, as she herself said with a shrug, decided to marry him. “It is always the women who marry the men,” she said, “isn’t it?”

She took on a handsome, unsuccessful young actor fighting a desperate battle for a chance on Broadway. Or in Hollywood, which he knew already was for him.

Nobody noticed him up to now. He did not know how to order a dinner, had never owned a tailor-made suit, nor a custom-made shirt. All these the beautiful, exciting, wealthy divorcee Ria Langham taught him before and after their marriage. She also set up and ran the first home of his own he ever had.

“He knows I rate it,” Ria Gable said to me at lunch in 21 on a day when the headlines screamed that she wouldn’t divorce Gable so he could marry Carole Lombard, “his best girl,” until she, Ria, received a settlement of $300,000.

“I’ve always told him he could have a divorce any day he asked me for it. And he can. Today or tomorrow. But he’s a businessman as well as a movie star. A great guy, Mr. Gable. He knows one must be business-like about these things. It’s only fair. I gave him a good many years of my life and taught him a good deal.

The second act curtain of the Clark Gable life fell upon the death of his third wife, Carole Lombard.

The story of Carole’s death as it happened to Clark Gable has never been told, but I think it should be now. Because now his life is over and you can never know him, nor know what he was unless you realize that he had to become another man when Carole was gone. What kind of a man that would be was, for a time, in doubt.

The first, his boyhood, his 12-year struggle when nobody on the road, Broadway, in stock or Hollywood saw anything but a big guy with ears. Up to the moment when with his smash hit in “A Free Soul” the public made him a star and kept him a star until he died a few days after finishing his last starring role with the only woman star of our day, Marilyn Monroe.

In the second act he and his wife Ria lived in a beautiful home in Brentwood, didn’t get along too well, separated. The two great peaks of “Gone with the Wind,” to me the all-time great actor’s performance of movie history, and his meeting with “my girl” Carole and their marriage.

Not quite three years they had together in what, you must believe me, was a glowing, riotously happy love such as I have never seen anywhere else.

I always like to think of a great love scene that happened between Clark and Carole Gable the very day after they moved into the new house, the dream house they’d built and furnished on the little ranch. Carole told me about it herself.

As everybody in Hollywood knows, Carole had a vocabulary. Knowing Carole as a girl with deep spiritual convictions, a real student of comparative religions and philosophy, I couldn’t reconcile this with her famous profanity. I asked her about it.

“Smoke screen,” Carole said, “protective coloration and camouflage. If you’re a young blonde around this man’s town, you have to keep the wolf pack off somehow and if you know all them words, they figure you know your way around and they don’t act quite so rough.”

Brimstone Words

Just after they’d moved in Carole got annoyed about a plumber who hadn’t done whatever it was he said he’d do. She let loose with words that smelled of brimstone.

All of a sudden, she felt strong fingers on her wrists. She was jerked around brutally and found herself looking into the kind of cold eyes with which Gable usually stared over a drawn gun.

“Listen, Baby,” he said in a when-you-call-me-that-smile voice, “if there is any cussing in this family, I’m man enough to do it myself.”

The screen’s famous comedienne of that day tilted her head sideways so that the shining curtain of her blonde hair swung free. She stared up at him and then fell on his chest, flung her arms around his neck and began to weep wildly.

“Hi, Honey,” Clark said, and through her sobs his bride said, “I’ve waited a long time for somebody to do that. Oh Clark I am glad I love you. I’m glad I married you.”

They meant to love happily ever after. They loved each other. They suited each other, which is another matter.

“It’s an extra dividend,” Clark said, “when you like the girl you’re in love with.” Carole was herself a country girl. She didn’t learn to hunt and fish, she’d always known how and loved it. Their long trips into the mountains were rough, rugged, honest camping trips and Carole, a very big star in her own right, loved it.

Then came World War II.

The president of the U.S. Franklin Delano Roosevelt, asked for stars to travel around the country selling war bonds and the first to volunteer was Carole Lombard Gable.

“I wish you could come too, Pappy,” she said a little wistfully as she packed. But Clark was working. He said, “Take Otto, then I won’t worry about you.”

Otto Winker was her personal press agent. Otto and Jill lived just down the hill and they were always coming up the hill to the Gables. The four of them were fast friends.

So Carole sold millions and millions of war bonds. People cheered her wildly in a dozen cities, and finally on a January day she could turn homeward. She sent the wire which announced the time of the plane’s arrival and added, “Hey, Pappy, you better join this man’s army.” She didn’t add even if you are 41, though they’d talked about it often before.

Mob Scene

Gable never went anywhere to meet her. It meant a mob scene. Carole pulled to pieces, himself mauled and smothered by crowds. The king had hit an all-time high about then.

So he didn’t go that afternoon either.

He asked the studio to send a car and chauffeur and a couple of men from the publicity department to handle her arrival. And he stayed home to prepare a welcome, such, he thought to himself, as no wife and sweetheart ever had before.

He and Martin, the Negro who’d been with him so long, set the table. Carole’s maid, who worshipped her, and Jean Garceau arranged such flowers as were never seen, and put fresh candles everywhere. Clark built a big fire with pine cones on top and then sent Martin down to bring up Jill Winkler, to be there to meet her husband.

“It’ll sure be nice to have mother back,” he said to Jill when she came in, “life without her around ain’t hardly worth living.”

A boy named Larry Barbier was waiting at the airport, Howard Strickling was away. Keeping the car ready, hoping to slip Carole through. Larry thought the time began to drag beyond normal.

After a while he called Ralph Wheelwright, Howard’s right hand and said: “The plane’s late but you can’t find out anything. You’d think the war was being fought next door. Carole and Otto and Carole’s mother are the only civilians on the plane.”

Ralph said, “I’ll call Clark and tell him and it’s late. Stick around and let me know.”

The next time Larry called he said, “The plane’s down.”

They moved fast then, thinking of Carole, thinking most of all of Clark, waiting. They plugged any calls through the studio to the Gable house. Eddie Mannix, the producer who was Clark’s close friend, said he’d meet them and go out to Clark’s with them.

To him, when they met, Ralph said, “They’ve seen it. It’s on fire!”

Gable opened the for them. Behind him they could see the table with the candles all alight, the heaps of presents, the glorious red roses that were Carole’s favorite flowers, the snapping fragrant fire, the slim tiptoe figure of Jill Winkler, waiting.

The moment he saw the two men, Clark’s face went still and green.

Eddie said, “Carole’s plane is down, in the mountains. We’re going. You ready?”

Plane’s On Fire

Quietly, Clark said, “In the mountains? Yes, I’m ready.” He went into the gun room and came back loaded with sweaters. He said, “You fellows may need these, it’ll be cold in the mountains.” Then he put an arm around Jill. He said: “You stay here, Jill, your mother’ll come. Maybe—it’s all right. You start praying, will you?”

They got in the plane and flew to Las Vegas.

Nobody in the plane said much. They were flying through a late afternoon, brilliant and glittering and clear as diamonds. In Las Vegas they went to the sheriff’s office and walked right into a posse that was being formed to go up into the mountains to search for the wreckage.

Somebody said, “How we going to know where we’re at—” and the sheriff said, “Hell, you can see the flames, plane’s on fire—”

A sound—the posse turned, and they saw Gable. Uncertainly, the sheriff said, “Well now—you got anybody on this plane you’re interested in, Clark?”

And Clark Gable said, in a perfectly natural voice, “Yes, my wife.”

Only then dd they know that there was anyone except soldiers on that plane. When Franklin Delano Roosevelt wired Gable that “your wife died upon the battlefield in service of her country as much as any soldier,” he spoke the truth. Sixteen of them died with her.

It was too dark for it to be possible to find anything that night. Afterward nobody could detail the strength and kindness of the big guy, as the long, terrible hours crawled by. Only, they said, he seemed to be the one taking care of everybody else, reassuring them, seeing everybody had sandwiches and coffee, remembering to phone Jill. A great rock in a dark, desperate hour.

At the first before-dawn gleam, they said, “We can go now,” and Gable stood up. After a moment, the sheriff said, “It’s a mean trip, Mr. Gable and—we don’t know what we’re going to find. Lots easier for us if you’d stay here. We’ll do our best and be back as quick as we can.”

A wave of fury passed over Gable’s face and left it white. Then, slowly, he said, “Yes. That’s right,” and sat down with Spencer Tracy, who’d flown up, to wait some more. Eddie Mannix, who’d never climbed a mountain and was in no condition to walk a mile, went with them all the way.

When they came down it was Eddie who went to Clark. He said, “We found the plane. There aren’t any survivors.”

“I—knew,” Clark said, “I’m glad you were there, Eddie.”

No Tears

The bravest thing Clark Gable did for his love was later, when they brought her down on horseback and he started forward like a madman.

“No,” Eddie said, “You owe her that. For her sake—you mustn’t.”

“I have to see her,” Clark said, and then, after a long time, he buried his face in his hands and turned away. No tears came even then.

“Life without her isn’t much worth living,” Gable had said to Jill.

What kind of a life would he make, what kind of a man would he be without her? What Clark Gable would come forth from this?

For a while, after the war, and before he found Kay, it looked like he’d gone to hell and the Gable we had known had died with Carole. His soul had certainly went down into fiery furnace.