1960: The Story Behind The Man (Part 1)

The Story Behind the Man

By Adela Rogers St. Johns

The Orlando Sentinel, December 25, 1960

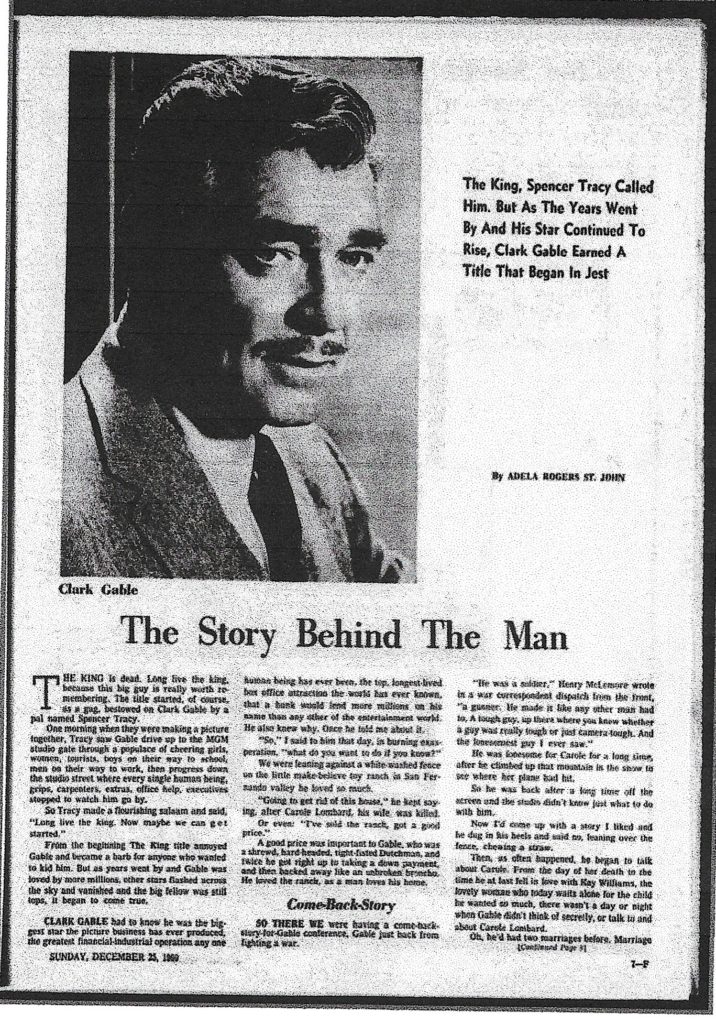

The King, Spencer Tracy called him. But as the years went by and his star continued to rise, Clark Gable earned a title that began in jest

The king is dead. Long live the king, because this big guy is really worth remembering. The title started, or course, as a gag, bestowed on Clark Gable by a pal named Spencer Tracy.

One morning when they were making a picture together, Tracy saw Gable drive up to the MGM studio gate through a populace of cheering girls, women, tourists, boys on their way to school, men on their way to work, then progress down the studio street where every single human being, grips, carpenters, extras, office help, executives, stopped to watch him go by.

So Tracy made a flourishing salaam and said, “Long live the king. Now maybe we can get started.”

From the beginning The King title annoyed Gable and became a barb for anyone who wanted to kid him. But as years went by and Gable was loved by more millions, other stars flashed across the sky and vanished and the big fellow was still tops, it began to come true.

Clark Gable had to know he was the biggest star the picture business ever produced, the greatest financial-industrial operation any one human being had ever been, the top, longest-lived box office attraction the world has ever known, that a bank would lend more millions on his name than any other of the entertainment world. He also knew why. Once he told me about it.

“So,” I said to him that day, in burning exasperation, “what do you want to do if you know?”

We were leaning against a white-washed fence on the little make-believe toy ranch in San Fernando Valley he loved so much.

“Going to get rid of this house,” he kept saying, after Carole Lombard, his wife, was killed.

Or even: “I’ve sold the ranch, got a good price.”

A good price was important to Gable, who was a shrewd, hard-headed, tight-fisted Dutchman, and twice he got right up to taking a down payment, and then backed away like an unbroken bronco. He loved the ranch, as a man loves his home.

Come-Back-Story

So there we were having a come-back-story-for-Gable conference, Gable just back from fighting a war.

“He was a soldier,” Henry McLemore wrote in a war correspondent dispatch from the front, “a gunner. He made it like any other man had to. A tough guy, up there where you knew whether a guy was really tough or just camera-tough. And the lonesomest guy I ever saw.”

He was lonesome for Carole for a long time, after he climbed up that mountain in the snow to see where her plane had hit.

So he was back after a long time off the screen and the studio didn’t know just what to do with him.

Now I’d come up with a story I liked and he dug in his heels and said no, leaning over the fence, chewing a straw.

Then, as often happened, he began to talk about Carole. From the day of her death to the time he at last fell in love with Kay Williams, the lovely woman who today waits alone for the child he wanted so much, there wasn’t a day or night when Gable didn’t think of secretly or talk to and about Carole Lombard.

Oh, he’d had two marriages before. Marriage was his way of life, and of course, there had been other women.

The wild volcano of romance and renunciation with Joan Crawford which rocked Hollywood because they were both married…one silly, too-tired-to-run-any-farther legal ceremony before Kay…but until Kay grew into the empty place in his heart, if he said “wife,” if he said “the woman I love,” he meant Carole Lombard.

“Right here one day,” he said quietly, “I said to her: ‘Mother, we’re lucky people. We’ve got this ranch, and while it’s not going to support us, it feels like a ranch, it smells and looks like a ranch; it’s not just animals and hay. We’ve got that house fixed just to suit us, we both have good jobs and friends and money in the bank and our health. God’s been good to us. Can you think of anything you really want you haven’t got?’”

He turned then to smile at me and he continued:

“You remember how beautiful she was? All shining. She had on overalls and a sweater—and she looked up at me with those laughing eyes and she said: ‘Pa, to tell you the truth, I could use a couple of loads of manure if we’re going to do any good with those fruit trees.’”

No Adonis

Gable let out that big roar of laughter, probably like the one he’d let out on that day when Carole was still beside him, giving him joy with her humor, her understanding of how scared the great lover Gable was of showing emotion, of acting romantic.

I waited and then went back to my job about finding a story for him.

“You won’t do this or that,” I said, “do you know what you ought to do? You know so much I suppose you know why you’re the king.”

“Yes,” he said, “I do.”

“Why?” I said.

“I’m not a bad actor,” he said, apologetically. “I work hard. I’m no Greek Adonis, but men don’t get sore if their wives or sweethearts like me, because I’m the common man and they know that. The reason they come to see me is because I know life is great and they know I know it.

“They take a look at me getting the best of earthquakes and storms at sea and wars and tigers and floods and airplane crackups, and they figure life’s a lot of fun. Life’s worth living even if it gets rough.

“They know that even if I had known what was going to happen to Carole, it was worth it. The price isn’t ever too high if it’s life.

“People don’t want to be depressed. They know life’s good if you stand up to it. That’s the way it’s always been with me and that’s the way it’s going to be. It’s all I’ve got to offer and I’m not going to betray them.”

He had been around.

I caught up with his early life. It comes back to me as a big slice of life, vivid, tender, desperate young, in the words of a girl who knew him very well before he became king of anything but her heart.

I still see her plainly, sitting on the witness stand in a drab, dusty courtroom, a sweet-faced going-on-40 woman. She was testifying in Gable’s behalf in a paternity action. As she told that story of first love, which was designed to show Clark Gable could not have been with someone else, you could see again the wide-apart eyes, the pointed chin, the eager mouth.

This was Franz Doerfer, who’d known Clark Gable, who’d known Clark Gable in a stock company in Portland, Oregon, when he was only 20.

“There wasn’t a day when we weren’t together,” she said on the witness stand, refuting the claim of the complainant. “We were in love. We even talked about getting married, but—” she chuckled, and the crowded courtroom chuckled back. “I was afraid he couldn’t support me,” she smiled at the big fellow with the high black head who now, 15 years later in 1937, was making something like $10,000 a week.

$10,000 A Week

Incidentally, Clark never forgot the amazed look given him by the recruiting sergeant who filled out his army enlistment papers when, opposite the question: What do you earn? Gable wrote “$10,000 a week.”

The case in which Franz was testifying was one of those unpleasant ones, an occupational hazard of movie stars, but it disturbed Gable profoundly.

In typical Gable fashion, for he consumed his own smoke if he could, he had told no one at the studio of the threatening letters from a woman named Violet Norton who said he was the father of her then 13-year-old daughter, and she could prove it. Then one day lawyers and detectives appeared at MGM and told Howard Strickling, head of publicity and Gable’s close friend, that unless $100,000 was coming up for this child’s support they would have to sue.

“You don’t want that, do you?” they said, “on the front pages.”

“Is she your daughter?” Howard asked, when he found Clark, and Clark said, “no she isn’t.”

“Look, you were only a boy, just off the farm, it could happen to anybody,” Howard said, and Gable, furious, roared back at him:

“I wasn’t just off the farm in 1922. I’d spent a lot of time in the oil fields. And anyway, it didn’t happen to me. If it was my kid, don’t you think I’d say so? And take care of her?

“I never was in England where she says this—this thing took place, I never saw her.”

“We’d have to prove that,” Howard said. “Where were you on such and such a night in 1922?”

To prove this Franz was in that courtroom. As she testified, their own romance came to life.

At first, Franz said, she and Gable had fought. They didn’t like each other as unimportant little members of that small stock company.

Then one day they kissed in the dusty shadows back stage and the world was new.

When the court decided Gable was not the father of Violet Norton’s child, and Violet had been sent to a sanitarium, the studio had a terrible time with Gable.

“I’ve got to take care of that 13-year-old girl,” he shouted at them. “She thinks I’m her father. It’ll break her heart if I just ignore her.”

But of course the lawyers wouldn’t let him. Admission, involvement. For years Clark talked about it. Franz, bless her, came to Hollywood, and worked at MGM, a good competent character.

Why Gable, the big tough guy, wanted to be an actor has always interested me. Why not an adventurer, an explorer, or a racing driver?

No man ever had such close men friends. He cared for his friends as much as he cared for woman. The greatest, the man he loved and looked up to, Vic Fleming, who directed Gone with the Wind.

The picture of Gable as the great lover is known round the globe. His story is told in terms of women, the five he married and a good many he didn’t.

The truth is different and more exciting.

Women fell for Gable because he was a man. He kept on being a man, which to him meant taking women in stride, keeping them in a proper but not paramount place, whether they were glamor girls like Loretta Young or society lovelies such as Mildred Huddleston Rogers. Given a comfortable home with a good-looking, kindly dispositioned wife in it, he was not about to go chasing out at night like a drummer full of marijuana.

Even in sex, the big guy had a sense of dignity, value and proportion.

Women were terrific. Fun. Necessary. He said so.

But so were lots of other things in a man’s life. A steady diet of feminine society and conversation would drive a man nuts. Sixty-two percent (his figure) of the time any man in his right mind preferred the company of other men.

Riproaring

This Gable was a two-fisted, two-bottle drinker Full of joie de vivre on one quart. Noisy, riproaring but still on his feet having a wonderful time on two. Slipping once in a while.

Anybody who thought Gable could hit that tree in the circle on Suset Blvd, cold sober, would have forgotten that Gable was the best automobile driver from coast t coast and that long before hotrodders became news he built his own cars.

The friend he spent most time with was Al Menasco, of Menasco Motors, an automotive genius and airplane designer. Hunting—fishing—camping—traveling the country in a station wagon. Ball games were ital. A real rough fighter with a Dempsey crouch and a disconcerting right.

As Clark Gable saw life, three things were paramount.

Love of his country, the great, big, free roaring America that had let him work and fight and starve his way from a midwestern farm to be a king.

Love of home, with his wife and family and children.

Love of his work if a man was lucky enough to love his work and Gable did.

Soon after he married Kay and settled down with her and her two children, he said to me, “I’m old-fashioned. This is what I believe in. Live while you’re young but remember what really counts.”

Women were important in his life. You will see that.

Josephine Dillon, the artistic Stanford graduate with her ideals of acting and the theater—what she taught him he could never have done without.

Ria Langham who showed him how to dress and which fork to use and whom he secretly admired because when she was finally divorced him after three years of separation, she made him come up with a business-like settlement, of some $300,000.

In Joan Crawford he met a woman who was his match in strength, in emotional power, who sept him out of himself for the first time in his life. He owed her a great deal for that. And for saying in the end “no, we can’t, we’d hurt too many people,” for they would have destroyed each other—and there might have been no Carole for Gable.

A great many people were surprised, some of them kicked up considerable rough house, when Clark Gable enlisted as a private in 1943.

He called me that day for news of my son Bill, who was already overseas with the Royal Canadian Air Force.

“Why are you going to enlist as a private?” I said.

“I got a date,” Gable said, “with this man’s army.”

A Capt. Gable

Then I remembered the last wire Carole Lombard has sent the day she took the plane from Indianapolis where she’d been selling war bonds—the plan that didn’t get across the mountains. “Hey, Pappy,” it said, “you better join this man’s army.”

From somewhere in Florida he called me to inquire where he’d find young Bill St. Johns when he got to England.

A letter I still have from my Bill says, “Who do you think rode over in a truck to my place today? A Capt. Gable!” And later Capt. Gable took young Bill St. Johns up to London on a shared leave. When Clark got back from the way he came to see me, to tell me everything Bill had said, how he looked, how much he’d enjoyed flying, what a job he’d done—all the things I wanted to hear about Bill who didn’t come back to tell me himself.

“I guess they are the finest young men this earth has ever seen,” he said. “It was an honor for me to go along with them in the same plane. You’ve got to have reverence for humanity when you see those boys and don’t you ever let anybody tell you different. They’re great.”

Courage.

He loved courage. “Courage and kindness,” he said that night, “these are how you know there has to be a God. Because men have courage and kindness.”

The last time I talked to hi a few weeks before the sudden heart attack, he kept talking about his wife’s courage.

“Kay’s made this such a happy house,” he said, “far more than I deserve. And now—this child. Her courage—with that heart she’s got. Well, we’re out of danger now, we’re past the fifth month.”

He never dreamed the danger zone might be there for him.

The Right Wife

Another things he said in that conversation keeps coming back to me today because I never heard him harder.

He said his last weekly paycheck had been for $48,000. “Because we went overtime,” he said. “Did you ever in your whole life hear anything so absolutely fantastic for an old crock like me when I only got $40,000 for making the whole picture of Gone with the Wind.

“Not but what I’d have made Gone with the Wind for nothing to work with Victor Fleming,” he added. “I know all about Gone with the Wind—once in a lifetime everything comes together at once—a story—a part—a director—a woman like Olivia DeHavilland—”

When Vic died some years ago, Clark said to me:

“The whole world looks different without Victor in it. In all our lives there are a few people—if they go the balance, the arrangement, the color changes. Vic was my number one guy. It’s hard to get my balance without him.”

One day while we were working on a Gable story, Vic said to me, “Clark ought to find a wife. He doesn’t know how to run his life alone. A man who’s always had a wife to run his life has no social sense. He gets lonesome. He gets involved with the wrong women. He needs the right wife.”

I mentioned Jean Garceau—the invaluable housekeeper—secretary—business manager—second mother who had been with him so long but Vic Fleming shook his head. He said, “A man like Gable is always at the mercy of women and women are without mercy. If they would let him alone—he might survive loneliness—but they won’t. We have to understand the background first—Mrs. Dillon—Mrs. Langham—Carole herself. God bless her. You understand what I mean?