1948: Still King Gable

Still King Gable

By Dorothy O’Leary

Movieland magazine, February 1948

Every time Clark Gable starts a new motion picture, the reporters, syndicate writers and magazine scriveners who want to interview “The King” if stood in line would queue from Culver City to Hollywood and Vine. Well, nearly that far. There are about 500 accredited writers covering Hollywood, all of whom scramble to be first to see Gable when production starts.

Just before cameras rolled on “Homecoming,” one of these scribes who has known Gable for several years saw him in a restaurant and asked to have the very first interview, adding, “I’d like the cream of the Gable news.”

“Chum,” replied Gable, “no matter how much you skim it, there will be no cream.”

Which is typical of Gable. He regards himself as an average guy; he doesn’t think he’s newsworthy. He knows he’s till “The King” on the MGM lot, but doesn’t understand why people are so curious about what he does, eats, thinks and says.

During interviews he is charming, amiable, and chatty, unless one makes the mistake of asking a very personal question, at which he will raise an eyebrow, calmly ask “Are you kidding?” and change the subject. He can get away with this, without rancor from the press, because he is that rarely-found character—a rugged, regular guy who possesses a great personal dignity.

Gable never permits fans, associates, even friends or super-snoopers of the Fourth Estate to break down the personal privacy to which he believes he is entitled. Yet with his camaraderie counter-balancing his dignity, everyone agrees he’s tops among swell guys. You’ll never hear a gripe about Gable.

A few months ago after Gable had been to Indianapolis for the auto races he went to Detroit, picked up a new car and drove back to California. Alone. He likes to take trips alone. He likes to stop at motels when and where the fancy strikes him, without fuss.

One of his stops was in Amarillo, Texas, where someone informed the press that Mr. G was at a local motor court. Reporters broke speed records to get there. Gable was hot, dusty and tired after a long day’s drive and wanted a shower.

“I don’t think I said much more than hello, told them where I’d been and where I was going and yes, I preferred stopping in motels,” Gable recalled. “They probably said I was an unfriendly cuss and blasted me in the papers.” He never saw those papers, because he was off before dawn the next morning.

According to his new contract at MGM, Gable has four months off between pictures. And that means off. He doesn’t do anything with movies in that time.

“After seventeen years in pictures I’ve just managed to get things set about the way I like them. It took a long time, but I guess I’m lucky at that,” he grinned.

We were chatting in his pine-paneled dressing room, with its big, comfortable red leather couch and chairs, on the set of “Homecoming.” Gable had been doing an intensely dramatic scene in which he was severely wounded, in a hospital bed, with bandages and dirt on his face and Lana Turner as an adoring nurse at his elbow.

During our conversation he was repeatedly called back to the set for different angle shots of the action. But never a second was Gable worried about the “mood” of his acting. He’d stop telling is about his ski trip with the Gary Coopers, walk into the set, do his scene, come back and pick up the conversation about skiing. No histrionics. No artiness.

Gable treats acting as a job, to be as well done as possible. He’s bored to distraction with people who go into the artiness of the thing. He makes no pretense of being an arty actor. Yet he has consistently remained one of the best and most efficient—along with tops in popularity—in Hollywood. He always knows his lines, is never late, is amenable to direction, takes things in stride and does not get temperamental. He reminds one of a successful business executive following through on a well-planned business campaign.

Away from work, however, he doesn’t plan his activities.

“I like to do things spontaneously,” he answered to our question of what he planned doing during his vacation after “Homecoming.” “They’re more fun that way. Last vacation I did practically nothing.”

“Nothing,” he admitted, included the trip to Indianapolis and the drive back, two trips to Oregon for fishing on the Rogue River, a lot of golf—which he shoots in the high 70’s–and pottering around his 20-acre ranch in Encino.

“Pottering” was another typically Gablesque understatement.

“The ranch was run down when I came back from the Army, but it wasn’t my caretaker’s fault. He’s a good man,” Gable hastened to defend. “He couldn’t get materials or men to help during the war. The fences were falling down. The trees needed pruning, spraying, and cultivating. Deer that came in had eaten the shrubs and flowers. I needed a sprinkling system before planting more.

“As soon as I was back, I went into Adventure.’ Maybe I shouldn’t even mention that! When that was finished materials still were unavailable but after ‘The Hucksters’ I had better luck. I got some lumber—although the best I could buy was second grade—and built the fences.

“Then I located some pipe—secondhand of course—and laid out the irrigating system. Then I planted shrubs and fixed the trees, shade as well as citrus, and they take work,” explained Squire Gable, who, as you note, has just as much trouble getting building material as Joe Doakes.

“I like to potter around. It’s good exercise.”

That it is, if one builds fences, installs irrigation systems, cultivates, prunes trees and such. But what about the deer?

“They just sail right over the new fence. They eat everything and are really quite destructive. The county sent me a notice I could shoot five, but I just can’t do it,” said Great Hunter Gable.

“You mean you don’t shoot deer on all those hunting trips of yours?” We challenged.

“Naw. Haven’t in years. I like to shoot and I’m a fairly good shot. I see how close I can get and then feel satisfied that I could have bagged one. But I can’t shoot ‘em; they’re too graceful and gentle. I used to like hunting mountain lion, but that’s awfully rugged. You spend days on pack trips in spots like Arizona’s Kaibab Plateau or the High Sierra. I’d rather play gold or ski,” he grinned.

Somehow that grin, his aforementioned dignity and, when needed, his equally famous frown have accomplished for him something no other Great Lover of the Screen has known: the ability to keep his fans from literally pulling him apart. Don’t think he’s any less popular than others.

Gable has held his old fans and has a whole new generation swooning over his virile sex appeal. His fan mail still measures in the bushels, including scores of proposals every month. His pictures break box office records, even clucks like “Adventure.” Men like him, as well as women.

But his fans do their swooning from a distance.

When Gable first gained fame he started a policy of never giving autographs to “mobs,” on the theory that those were not real fans, although he never refused them to individuals or a small group. Word got around and this fact is still known. The autograph hounds, even in New York where they have nearly killed some movie stars, know that Gable does not tolerate being mobbed and they leave him alone.

Sure, they stare and wave. Gable grins at them, and they open a path for him. They don’t pull buttons from his suits or sleeves from his coats. That’s why when he goes to New York he doesn’t need a studio representative along for protection. He wouldn’t have one. He likes to travel alone.

Gable is unable to explain just what he does which inspires respect from fans. He says simply, “People are bothered by autographed hounds who let themselves be bothered. I don’t. I’ve never underestimated the importance of fans. I love ‘em. But some of those kids in big cities, particularly New York, aren’t real fans. The same ones have been around for years. They should be studying or working. Last Winter I saw one young man in that crowd that I remembered from seven years ago. I asked him, ‘Weren’t you hanging around for autographs in 1940?’ He admitted he had been and I told him it was high time he had a job. All he said was, ‘Yes, Mr. Gable.’ I don’t think he was insulted.”

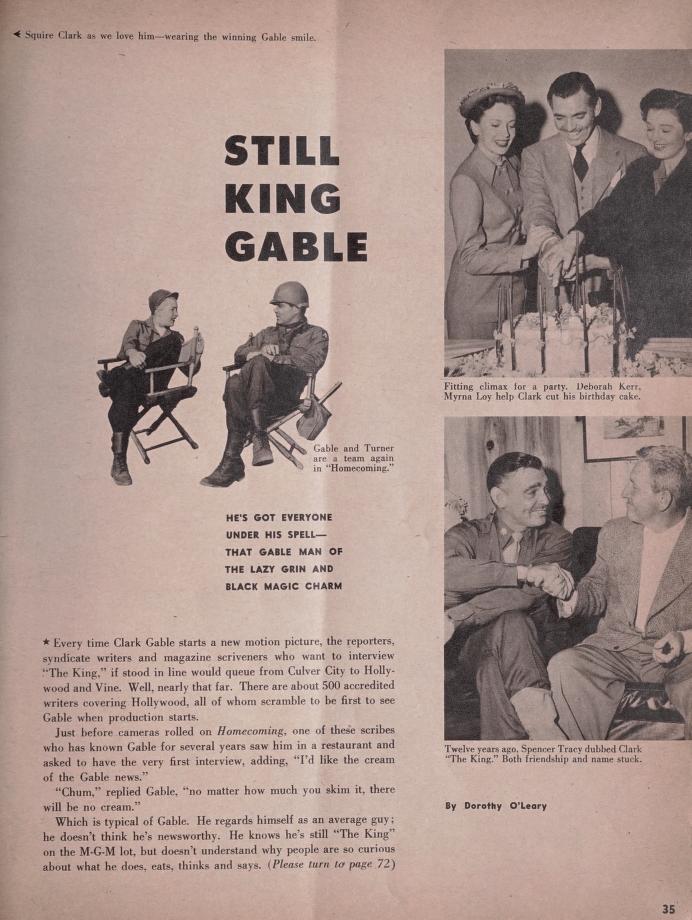

Gable has the faculty of arousing respect along with attention, as befits a “king.” And in case you don’t know how he acquired that nickname; it was about twelve years ago when he was elected “King of the Box Office.” His friend Spencer Tracy had a huge gilt throne complete with purple canopy installed in Gable’s dressing room and started calling him The King. The name has stuck. His only other nickname is Pappu, used only by a few of his best friends who remember it as the pet name bestowed on him by his late wife, Carole Lombard.

Flattery and fawning adulation make him sick; he dismisses them with a well-turned phrase or a simple “Are you kidding?” He has equal contempt for conceited people and poseurs. He looks for loyalty in friends, and gets it.

He likes women who are good sports and gay companions; who are chic and well-groomed on proper occasions, but who can be informal, too. He has dates with long-time-friend Mrs. Dolly O’Brien, with Ava Gardner, with Anita Colby and Virginia Grey but denies any romance.

Gable likes to laugh, is an amusing conversationalist, an excellent listener and good raconteur, if not exactly a crisp wit of the Noel Coward school.

He dislikes buffet dinners. He likes to sit down to a sturdy, well-cooked meal, served on time. He still likes turtleneck sweaters, but still dislikes dancing. He hates overheated rooms, gossip, backseat drivers.

The people he works with are the ones who really tell you what a great guy Gable is. There’s Hal Rosson, who has been his cameraman for fifteen years; Lou Smith, who has been his stand-in for eleven; and Chet Davis, head electrician on his pictures for an equal time. They all agree that he is “the sweetest guy in the world.”

Some stars are perfectly willing to have their benefactions, charities and kind deeds known to the public. Gable is affronted if anyone tells of his. The only occasion on record of Gable bawling out a fellow worker was once several years ago when he thoroughly dressed down a publicity man for disclosing one of his benefactions.

A few are known, however. There was the time during the filming of “Idiot’s Delight” when Gable learned that some dancers working with him were short of money. To “save face” with them, instead of giving or lending it to them, which he would gladly have done, he arranged for them to earn it, without their knowledge. He told the studio he needed extra rehearsals with them for several days—which he didn’t–for which they were paid more than needed.

As one of his friends, who insisted on remaining anonymous lest Gable think he were disclosing a state secret, said,

“If you were to ask the average star for a loan of twenty bucks he’d pull out a roll that would choke a horse, make sure that everyone saw it and peel off the bills, like a Secretary of the Treasury. If you asked Gable, he’d take you off in a corner so that nobody would see him doing you a favor or you wouldn’t be embarrassed. Then he’d just take the money from his pocket. He never flashes a roll. And he’d ask, ‘Is that enough?’”

The King, certainly, is regal, rugged and regular. Long live King Clark I.