1934: Clark Gable Cuts the Apron Strings

By William F. French

Photoplay, April 1934

A pawn for glittering women stars suddenly blossoms as an actor

The Clark Gable who played second fiddle to so many glittering female stars is no more. And, we might add, he was practically buried in “Dancing Lady.”

Clark Gable, the actor—a new thrill for the ladies and a pleasant surprise for the men—comes to life.

And all Hollywood is mighty well pleased.

Hollywood didn’t hold it against Clark Gable that he was popular with the fair sex. It even forgot that he did a minimum amount of acting per picture, while he was playing foil to Garbo and Shearer and Crawford and Harlow. In fact, it actually forgave him for demonstrating how the rough and tough, hard –to-get hero finally succumbs to the relentless heroine in boudoir, grass hut, or what else.

Everyone on the lot from director to grip’s helper, would tell you, on the slightest provocation, that it wasn’t Clark’s fault. The girls fought to have him play opposite them, and the executives regularly sacrificed him to make a maiden’s heyday.

Besides, Clark was there to reflect the glory of the girls, and to thrill feminine enthusiasts in Dubuque and New York City. His job was to inspire tired shop girls with aching feet and console weary spinsters—and he did it uncomplainingly. Quite willingly, in fact.

Now Clark is a little sorry he was so uncomplaining—but, after all, you can take his word for it that his was a soft berth. “Like going to fame in a wheel chair,” to use his own expression.

“It’s all crazy,” he had said, “but it sure is a lazy man’s job. Little work, plenty of money, and lots of time to enjoy yourself. Just luck for me, that’s all—just a big apple of luck dropped in my lap.”

And, after the bitter struggle Clark had known, it was an apple of luck in his lap.

Clark harbored no illusions of grandeur. He knew he was just a pawn, put there to reflect the glory of the women stars, and to bring a few “ahs” and “ohs” from the more susceptible femmes in the audiences.

Occasionally he would say, almost timidly, “Gee, I wish they’d give me a chance to do some comedy. That’s what I was best at in the stock company back in Houston.”

But Gable had too much box office value as the heavy menace to the purity of the lady stars on the MGM lot, to be allowed to go fooling around with comedy. And as the he-man who repulsed the alluring girls, Clark was just too sweet. So bang! went his prospects for a real chance to show his wares.

It was more or less Clark’s own fault, of course—and he admitted it. He didn’t fight executives, casting directors, writers and directors all over the lot, trying to get better parts. Unlike Crawford, and the other women stars, he didn’t battle incessantly to reach the top.

Clark was never aggressive—and none knew it better than he. Life was a shoe that Clark liked to wear easy.

So, after the girls got what they wanted Clark’s parts were made up from what was left.

Consider “Red Dust,” for example. That story was built for a woman, fitted to a woman, directed for a woman, and cut for a woman.

Originally it was bought for Garbo. When Harlow was cast for it, it was re-shaped for her. Then Gable was put in for Harlow to sharpen her teeth on, so to speak.

In the past he has been cast so that the women in the pictures could fight over him, supplying an attractive background to set off the feminine lead.

Clark never kidded himself. No one knew these facts better than he; but his contract was long and his salary continued, week after week—freeing him from old worries and old fears. If his parts were not to his liking, the checks were, and he was willing to play second fiddle for the security he felt.

Some said Clark wasn’t fair to himself, or to his public, in not demanding a chance to do the things of which he felt capable—while others marked him as smart for not bumping his head against a stone wall.

Perhaps the hard knocks of the past had been bad for Gable’s confidence in himself—but, at any rate, he did string along, taking what was given him with that boyish smile that won so many friends—and fighting for nothing at all.

All that, however, is a memory now.

Clark Gable has been shaken out of the arms of the glamorous stars and put on his own feet. He has cut the apron strings that for years had bound him to minor parts, and has pushed out into the sea of performance where he will have to swim or sink. And, so far, he has done a grand job of swimming.

Whether Clark would have dived in on his own initiative is problematical. Many times he has said that he prefers to play second to stars, letting them bear the responsibility of the picture’s success, and often he has confessed that the thought of carrying a picture alone scares him. He always claimed he didn’t want to be a star; that he just wanted to play good parts.

But Clark is likely to find it is too late to turn back now—that his screen admirers won’t let him, since they’ve had a sample of what he can do.

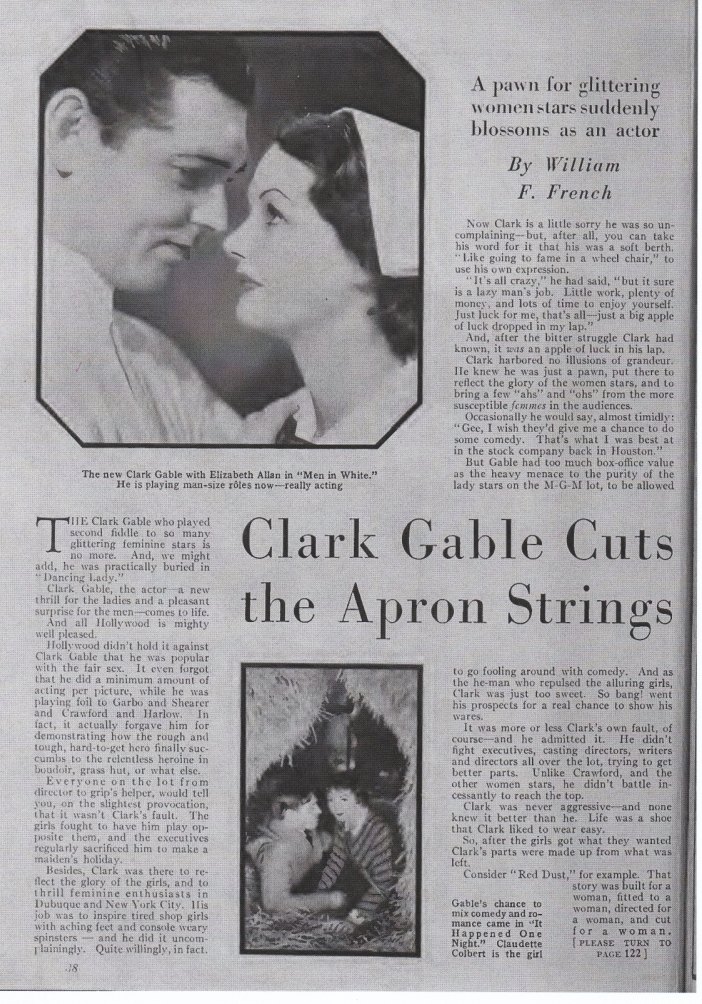

And his studio’s response to this demand is “Men in White,” with Gable starring, supported by Myrna Loy, Jean Hersholt and Elizabeth Allan—and the bringing in of Frank Capra to direct Gable in “Soviet.”

For Capra is largely responsible for the new Gable—the Gable that will have as many men, as he has women, followers.

It all happened this way:

Columbia decided they would like to make a picture with Robert Montgomery, and had a story written for him—a story made to order for his particular type of humor.

Then it came about that Columbia had its choice of using Montgomery or Gable.

“Well,” they debated, “Gable has done nothing of late to rave about—but there’s no denying he has a way of drawing the women into the theaters. Maybe it would be a good idea to do a picture with him. Only if we do, we’ll have to write something with a good part for a heavy lover in it—because he could never handle the humor in the picture we’ve just had written for Bob Montgomery.”

Frank Capra had never heard Clark’s plaintive little “Gee, I wish they’d let me do a comedy,” but, as he told me, he had often been struck by the strong human character of Gable.

“You could see it sticking out all over him,” Capra said, “and I’d been playing with the notion that I’d like to give him a chance to be his real self, and to forget the heavy parts that has been wished on him. So I said: “Don’t change a line of that story and Gable will surprise you.”

That is the inside story of how Gable was cast to the lead with Claudette Colbert in “It Happened One Night.” How fully he justified Capra’s confidence in him, all of you who have seen the picture know.

His performance in that is rated as “top.” His handling of the comedy hitch-hiking scene is classed as a “natural.”

Only the other day, Clark said to me, “I hope my work in ‘It Happened One Night’ makes the picture-goers feel I ought to be taken off the heavy lover roles and given some good parts. I’m not asking to be starred. I don’t want that. I just want to get some good parts, and not always have to play heavy opposite a woman star.”

So, men readers, playing hot love scenes with Jean Harlow, Joan Crawford, et al., apparently isn’t all plum pudding, after all. At least one man in America would rather do something else.

Being “typed” in Hollywood is a serious business—and it has handcuffed more than more competent actor to subordinate parts.

“I knew I was ‘typed’ as the heavy lover,” explains Clark, “but everybody seemed to think I was so lucky being cast opposite stars like Garbo and Shearer and Davies and Crawford, I didn’t have the nerve to complain. I would have been crazy to expect the studio to write down the parts of such stars in order to give me a chance to do something—so I just went along.”

And how Clark just “went along” is evident in his part as stage manager in “Dancing Lady,” a part which even the studio itself admitted had been milked white by Warner Baxter in “42nd Street.” After Baxter was done with it there wasn’t enough nourishment left there to support a healthy extra.

But a stage manager was needed to build up Joan Crawford’s part, and Clark’s “type” was desirable for her to work on. So Gable it was.

If the feminine star needed a lover in the form of a gambler, as did Norma Shearer in “A Free Soul;” or in the garb of a minister as did Marion Davies in “Polly of the Circus;” or in the stripes of a jailbird, as did Jean Harlow in “Hold Your Man,” it was up to the heavy sheik to fit in. And Clark Gable was getting to be the “fittingest in” actor in all Hollywood.

In casting him, no one ever said, “Now, let’s see, what sort of part should we get for Clark Gable?” Far from it. What he played depended upon what type of character was needed to round off the star’s background.

But now, with other studios realizing this natural “threat” (so far as the women are concerned) has real acting ability,, you can expect to see parts fitted to Gable, instead of seeing Gable whittled down to fit parts.

And how does Clark feel about this sudden about face of Hollywood’s attitude regarding him?

We told you he was as natural and unassuming and boyish as anybody you could ever hope to meet. To use an expression of one of his friends: “There’s not a swelled bone in Clark’s head.” So you probably won’t be surprised to learn that when a day or two after seeing the preview of “It Happened One Night,” Clark took the first opportunity to thank Frank Capra. They chanced to meet on one of Hollywood’s main thoroughfares. Both were in their cars—and the traffic was moving.

Leaving far over the edge of his own car, Gable called his appreciation to the director—and he didn’t care if all Hollywood knew how much gratitude he felt for the opportunity that had been given him.

Clark has always believed that Hollywood has been more than kind to him, and right now he’s like a kid with a new car. Just plain tickled, and eager for another chance to show his stuff.

That night at the preview, when “It Happened One Night” ran fourteen reels till midnight–with the audience so thoroughly enjoying the new Gable and so heartily sharing his adventures that they never realized the picture was some four reels over length–a new confidence and a new ambition were born in Clark. Not that he sees himself as a great star now–far be that from one of Gable’s modesty–but he does feel pictures have more to offer him than ever before.