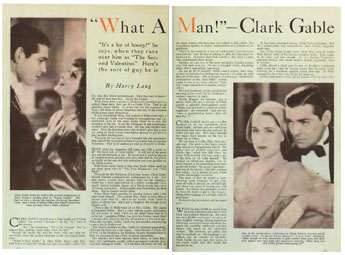

1931: What a Man!–Clark Gable

By Harry Lang

Photoplay, October 1931

“It’s a lot of hooey!” he says, when they rave over him as “The Second Valentino.” Here’s the sort of guy he is

Clark Gable himself gets a huge laugh out of being called “the second Valentino”—or the “It” man of the movies.

“Aw,” he comments, “It’s a lot o’hooey! But as long as they spell my name right, what the hell?”

Around the studio the men he works with razz him unmercifully about his sudden eminence as the sex appeal champion.

“What-A-Man Gable” is what Wally Beery calls him. Cliff Edwards calls him things, too, but you couldn’t print ‘em!

But they like Gable tremendously. He’s that sort of man—the sort of man men like. As for the women…

Well, every time a group of Hollywood’s prettiest get together these days, they say it’s a Gable Club. They’re all gabbling about Gable. It seems the lad has captured the fancy, not alone the screen fannettes, but also of the loveliest of the screen stars themselves.

It is a remarkable thing, but typical of Hollywood, that a few years ago Gable was working in inconspicuous and unpublicized parts at the same studio where he is now the sensation of the lot. Even the waitresses in the commissary wouldn’t give him a tumble then. He was just another ham actor. Now the feminine stars who wouldn’t give him a nod are using their coyest come-hither glances to get him to play as their leading man.

The parts he has played have brought him the popularity that caused the hysterical writers to proclaim him as another Valentino. That is all applause and no discredit to Gable.

Soon some fan magazine will come out with a story on “The Love Life of Clark Gable.” It will tell of his great lure and all that sort of rot. He never had it until he played sex-appeal parts in pictures, and up to that time he was about as deadly as the nice lad who measures out your gasoline at the filling station.

Hollywood never made a fuss over Rudy either until he got those great roles in “The Four Horsemen” and “The Sheik.”

Through all this fluttering of feminine hearts, Clark Gable himself remains comparatively unimpressed by it all. Not that pretty women don’t interest him—on the contrary, Gable has a keen appreciation of a pretty young girl—of a neatly turned feminine figure—of a lithely lovely leg—of a vivacious young face. Impersonally and objectively, he liked them. But he doesn’t marry him.

When Clark Gable marries, he marries women quite a bit older than himself. The current Mrs. Gable is more than a decade older than he. She’s in her forties, while Gable is thirty or thirty-one. She’s got a daughter old enough to be Gable’s wife.

There’s also in Hollywood an ex-Mrs. Gable. Her name is Josephine Dillon. She’s a voice culture expert, and insists she did much to train Clark for the talkie fame that he’s achieved. Josephine Dillon, too, is in her forties—more than a decade older than the lad who divorced her a few years ago. When she was Mrs. Gable, Clark was just another actor trying to get a job in Hollywood.

And there’s another ex-Mrs. Gable in existence somewhere, although the facts are a bit vague. Close friends of Clark tell of how, on his birthdays, for instance, he gets telegrams from a nine or ten year old son of his, in school somewhere.

But whether he’s been married three times, or three hundred, that indefinable quality called sex appeal certainly does currently belong to Gable. It’s manifest off-screen as well as on, those women who have met and talked to him admit. It’s as synthetic quality in Gable, compounded by a number of ingredients.

There is, for instance, a sort of confidential “just-between-you-and-me” way he has of talking to girls he’s just been introduced to. It makes them feel, somehow, that here’s a man who understands them deeply.

Besides, he’s got two of the most intriguing dimples women ever laid their eyes on. He has a strangely frank, disarming smile, that’s appealingly ingenuous.

He has an air of sincerity which women suspect isn’t true, so they’re interested in finding out what he’s covering up with that air of sincerity. His personality is a strangely paradoxical combination of the “lady-killer” women ought to run away from, and the “little boy” type women love to mother, as they call it.

He’s not handsome, in the conventional meaning of the word, but he challenges a woman’s interest at sight.

Hedda Hopper, for instance, put it neatly when she saw a photo of Gable astride a splendid thoroughbred steed. “When you can look at a man on a thoroughbred,” she remarked, “and not say ‘what a good-looking horse,’ then the man has ‘It!’”

Clark Gable hasn’t got a swelled head by all this excitement about Clark Gable. At least, not yet—and those who think they know the man feel sure he won’t ever get one. He’s been through too many hard knocks on his way to where he is today.

He was born in Cadiz, Ohio, three decades ago. His stock is that lusty, sturdy clan known as Pennsylvania Dutch. His father was an oil-field contractor, and Clark—they called him Bill then, because William is his real first name—put in his licks at oil wells himself. He worked on Oklahoma derricks, but always wanted to be something more than an oil well worker. He says it’s just luck—just one of the breaks—that he’s a screen star today. As a matter of fact, Gable worked unceasingly toward it.

The story of how he joined a barn-storming stock company to get away from oil fields is already an oft-told tale, and there’s no sense in boring you with it here. You know, too, probably of how he froze his hand to get to the Coast—riding blind baggage on a freight train in midwinter.

He knew what he wanted, and he aimed at it.

With the first $2,000 he saved from his stock experience, he went to New York and polished himself up. He spent the whole $2,000—and more—on voice culture, English training, diction correction. Gable has never had much schooling, beneath his carefully cultivated exterior, there’s still much of the oil-derrick worker. His manners are polite, but they’re studiedly so. His language is excellent, but he watches it carefully. Clark Gable, as you meet him today, is the Clark Gable that Bill Gable has learned to be.

As has been remarked before, Gable isn’t handsome. But he’s considerably less unhandsome than Nature originally made him.

One of the things people notice about him when he smiles that dimply smile of his are his exquisite teeth. They ought to be—they cost him enough. It was Pauline Frederick’s personal dentist who made Gable’s dental equipment what it is today.

Gable played a small part in one of Pauline’s companies some years ago, when he became aware that his teeth would certainly be a handicap against screen close-ups.; So Polly arranged to have her own dentist fix them up.

Gable’s ears used to stick out a great deal more than they do today—like Eddie Cantor’s. But that’s been overcome, too. It was easy. Gable may not be handsome—but he’s a beauty compared with the Gable as was. He’s a worthwhile lesson to any man or woman who is ambitious enough to overcome facial defects.

He has a noticeable measure of self-consciousness. His hands, for example, are rather large. He is patently worried about what to do with them. He is keenly clothes-conscious, and always dresses well. He liked to dress up. The biggest surprise that ever hit one of his acquaintances who “knew him when” came on Broadway one evening when Gable had just gotten out of the press-your-suit-while-you-wait ranks. The acquaintance beheld Gable resplendent in full evening dress—not tuxedo, but tails—with all the trimmings; high silk hat, white gloves, silver flask (filled) and even a cane. The acquaintance will never be the same.

Now that he’s making his money, Gable buys clothes in quantities. He’s fair game for the haberdashers of Hollywood. Clark may go unto a store with the intention of buying nothing but a necktie; when the salesmen get done with him, he’s probably bought three or four hundred dollars’ worth of clothes.

On the other hand, when things weren’t breaking well for Gable, he paid no attention to his appearance. It’s a manifestation of a chameleon-like trait in the man—he fits his mood and his self to circumstances.

By reason of that, he appears at home in whatever gathering he finds himself. When he’s shooting craps with a gang of studio juicers and grips, you couldn’t pick him out of the crowd, he’s so much one of them. Set him down in a society drawing room, and he can bow and scrape and broad-A with any of them. He always reflects, in his apparent personality, the group of which he’s currently a part.

He’s childlike in his reactions and enthusiasms. He has no definite hobby, but goes through a steady and rapid succession of passing fancies—like a kid with toys. He may be crazy about this game, or some new possession, for a week or two, say. Then, like a kid grown tired of a new plaything, he forgets it completely.

He sticks to golf, though. He loves it. And he rides a lot—but, more to keep his figure than because he likes it. He really has a splendid body—broad-shouldered, narrow-waisted. He’s an inch better than six feet tall, weighs 190, and is as healthy as a young steer.

He smokes, and drinks, but neither to any excessive extent. Food is no problem—there’s nothing in the line of foods he won’t eat. He drinks great quantities of coffee. And late at night, he likes to go into a restaurant and order eggs and bacon and hashed-brown potatoes.

He has all the usual actor-superstitions—won’t light three smokes on one match, won’t let people whistle in his dressing room, and goes crazy when a mirror is broken.

He wants to own an airplane now. The first time he flew—it was from New York to California—he climbed out of the plane pretty sick and vowed he’d never like airplanes. Then he went to the San Diego naval flying base on a picture went up with some of the navy’s best flyers, did all the stunts they could think of, and came down wanting to own an airplane.

His big ambition is to stay on top of the heap, now, for about ten years and make a lot of money. Then he wants to quit working and spend the rest of his life traveling.

You’re a grand guy, Clark. Good luck to you.

One Comment

steve

Did anyone notice that during this time the article says close friends of his say that he gets a letter from a 9 or 10 year old son. What ever became of this story and if it is true that would be something else.