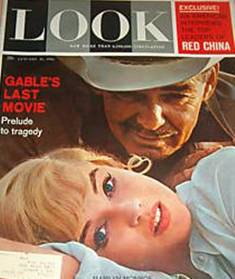

1961: Gable: Last Look at a King

Gable: Last Look at a King

by Stanley Gordon

Look magazine, January 31, 1961

Thirty years ago, Clark Gable slapped Norma Shearer’s aristocratic face in A Free Soul and launched his own personal era of heroes who take no nonsense from women. In his heyday, he was lusty, challenging, unsophisticated. He grew more stolid and thoughtful after the war years, but a glint of hell-raising humor remained. The millions of people who paid $500,000,000 to see his 60 or more movies never wavered in their affection. Wives took their husbands to see Gable pictures, and fathers took their sons, because they admired him as a man.

There was no one anywhere who ever looked quite like Gable, or who could approach the cumulative dignity and glamour of his life and career. “He’s not a man—he’s an institution,” a Hollywood producer once said. As with royalty, Gable was regarded by many people as a personal friend, but few in the crowds that always surged around him dared touch him or call him anything but “Mr. Gable.”

Millions of words were written about him throughout the world. Everybody knew the vital statistics of his life: his beginnings as a farm boy, his roustabout years before getting established, the vicissitudes of his five marriages, his war record, the enormous sums of money he earned (for his last picture, United Artists’ The Misfits, he got more than $800,000). But Gable was never an easy man to know or understand. In the early days, he talked freely about himself. As the years went on, when questions turned to his private life, he would make little comment.

What kind of man was the “institution” Gable?

“Originally, I thought he was a simple, forthright man who sailed through things triumphantly,” his last director, John Huston, says. “I discovered he was a very complicated person who took everything with much seriousness. The Misfits is not superficial, but a profound statement of human values. Gable respected this, and his handling of the role shows his innate profundity as a man. I could never get to the set ahead of him. He was always there ready to work when I arrived. Sometimes, we had to wait several hours for Marilyn Monroe to show up, but there was never a single complaint from gable. It took me a while to find out that these delays outraged him. He had an exaggerated sense of responsibility, but curbed it by his calm self-control.”

His first wife, Josephine Dillon, remembering him as a young man, said he was “deep, quiet and thoughtful, a gloomy, dead-pan Dutchman with 300 years of Pennsylvania Dutch behind him.” What most people remember about him, from casual meetings, was his genuine warmth and charm. When Gable was talking to you, he gave you the feeling that you were, at that moment, the most important person he knew,” says a veteran Hollywood correspondent.

Basically, Gable was neat, methodical, stubborn, punctual and cautious. Although he was worth $2,000,000 and could have lived in a Beverly Hills mansion, he preferred his secluded ranch in the San Fernando Valley. He lived with his fifth wife in a white-brick farmhouse that he and Carole Lombard had remodeled shortly after their marriage in 1939. 9Carole had all the chairs built oversized to accommodate his big frame.)

Gable’s father, until his death some years ago, lived close by, raised chickens and spent time at his son’s ranch puttering around. “The relationship between the two men was fascinating,” says a friend. “Both were big, rugged men, strongly disciplined; there was never any show of sentiment between them. I doubt if either ever out his arm around the other, and they never wrote letters. But each always knew where the other one was.”

Gable was mostly self-educated. As a youth, he received only a sketchy high-school education. After he became a success, he discovered the value of reading. He read everything: biographies, historical novels, farm pamphlets, sports books, particularly everything on golf. He was an actor who worked diligently on the role he was to play. His seriousness about acting astonished many of the bright, young, “dedicated” actors from New York. He once said his tombstone should read: “He was lucky—and he knew it.” But he never ceased working for the “luck” that stayed with him.

There was always a woman in Gable’s life. His matrimonial record was the most unconventional thing about him and didn’t seem to fit the Gable pattern. In his movies, he mockingly challenged the dames to hook him; in life, he was always hooked. In every romance, gable was boss, and he never had a scandal. His first two wives—one an intellectual and the other a gay, worldly divorcee—were older than he. His fourth wife was a British socialite whose party-going tastes did not agree with his quiet way of life. Between these marriages, he kept company with a number of beautiful and prominent women. After a parting of the ways, however, every one of them, whether wife or girl friend either kept silent or sang his praises. As a Gable intimate explains, “He was honest—and lucky, and he never hurt anybody. The women respected him for this, and there were never any public scenes.”

His third marriage, to Carole Lombard, is one of the legendary Hollywood love stories. His final marriage was to a woman of remarkably similar temperament—Kay Williams Spreckels of Erie, Pa., onetime model, bit actress, former socialite wife of two millionaire husbands, now in her 40’s and expecting his first child. Kay was the happy culmination of a lifetime devoted to the love of the unusual and fascinating women who were either as brainy as he or just as rich.

Gable had a mixed strain of melancholy and conviviality in him. On occasion, particularly before his last happy marriage, he was a two-fisted drinking man, in private. He drank anything offered to him. But more than once, after a warm day on his ranch, he would say, “Do you know what I’d really like to drink? A big stein of root beer with ice floating in it.” “We consumed a lot of root beer sitting in the shade of the pepper trees at his ranch,” says his oldest friend, Al Menasco, a former automobile dealer. “He was never a daytime drinker, and it never interfered with his work.” In his work, he was always a lone operator. Some stars willingly surround themselves with worshiping retinues, but Gable drive his car to and from work alone. He did like to have familiar faces around him at work—the same make-up man, wardrobe man, stand-in—his most trusted friends. He did not subscribe to the old Hollywood custom of seeking friendships by gibing expensive gifts to the crews on his pictures. True to his youthful small-town standards, he believed a man should be paid only wages for his work. But he won crews’ loyalty by praising their work to producers and directors when occasion arose. Many studio workers have better jobs because of a quiet recommendation from Gable.

A frugal man, he gave no big Hollywood parties. He kept his home inviolate to all intruders/ He didn’t throw his money away and hated to waste other people’s. he never went in for coproducing films or got into outside businesses. He invested his earnings in Government bonds and securities, where he felt they would be safe. In his first flush days in Hollywood, he was taken for sums of gambling money by “high rollers.” But it never happened again. He did not frequent Las Vegas and limited his gambling to a friendly poker game with his cronies—50 cent limit. If he won or lost $20 in a game, he considered he had had a big night. For a time, he engaged in a continuous floating gin-rummy game with Adolphe Menjou on movie sets, but no great sum of money changed hands.

His presence on a movie set had a calming influence. Even the toughest directors and the most difficult actresses changed when they worked on a Gable picture. “If they came in like lions, they went out like lambs,” says a Gable co-worker. “He was always the biggest man on the set.”

He was also the most approachable. His dressing room door was always open. Between scenes, he would visit with anybody there, often looking over a gun or fishing rod that some member of the crew had brought in for his expert appraisal. He had unfailing courtesy with strangers and suffered bores and boobs like a gentleman. But he could freeze like an iceberg when anybody became too personal. “He was a great ribber,” recalls Lew Smith, his stand-in for 20 years, “but he only ribbed people he liked, and in a non-sarcastic way. He never hurt anybody. His philosophy was live and let live. His favorite expression, when he heard an exaggeration voiced by someone near him was, ‘Yeah, that’s what the girl said to the sailor!’ He knew it was corny, but he got a kick out of it.”

His closest friends among actors were Gary Cooper and Ward Bond, both outdoorsmen like himself, and David Niven, whose wit delighted him. Gable loved jokes, but shyly felt he couldn’t tell them well. Whenever he brought a new joke to the studio, he passed it on privately to the best raconteur in the cast and listened appreciatively to him tell it. He carried on a friendly rivalry with Spencer Tracy, who liked to rib him about being ‘King”. A close friend of both men says, “Tracy would have given his right arm to be as popular as Gable was, while Gable always wanted to be as fine an actor as Tracy. It bothered him that he couldn’t play great character parts. He tried it once in Parnell, but the fans didn’t like it. The public wanted him to stay forever and uniquely Clark Gable.”

He was a hero to his entire profession, and he himself was a hero worshiper. In sports, he had special pedestals for Bobby Jones and Joe DiMaggio. He considered Marlon Brando, whom he never met, as the actor with the greatest talent in the generation that was to succeed him. Actors and actresses liked to work with him, because he became excited and enthusiastic about their performances if they were goof. “Boy, can that fellow act!” he would exclaim over some actor whose work he admired. Often, it was that of a newcomer whose talent he hadn’t noticed before, because he usually only went to movies in which he or his friends appeared. Through the years, actresses like Lana Turner, Ava Gardner and Grace Kelly had reason to thank him for giving unselfish boosts to their early careers by insisting on costar billing.

His father was a Methodist, but Gable had no particular religion and never talked of faith or philosophy. These, he felt, were personal affairs. Yet he had great respect for others’ religions. One Sunday last summer, at St. Cyril’s Roman Catholic Church in Encino, California, communicants at an early Mass saw Gable, dressed in a dark-blue suit, walk in with his wife and her two children. He was there to witness the first communion of Kay’s son Bunker, who is being reared a Roman Catholic.

To the end, his home life was the most important part of his existence. He was sentimental about birthdays, anniversaries and holidays and always celebrated them in the grand manner. Kay and her two children—who called him “Pa”—were always with him.

Kay has the chic and salty humor that pleased Gable in a woman. During their long stay in Reno, Nevada, while The Misfits was being filmed, living away from home in intense heat with two small children and a hard-working husband absorbed in his role, Kay had the usual upsets of any American housewife. One evening, she exploded in jest, “God, what a day! All morning, trouble with the kids. A fight with the cook in the afternoon. Clark, cranky after work. And all day long, I spray, spray, spray these old hairs of mine!”

Gable laughed and said that reminded him that one of the children had wondered why Gable’s hair had suddenly gone from gray to black during the filming of The Misfits. “Why is Pa’s comb such a funny color?” Gable was always immaculate in dress and appearance, but never made any pretense of trying to be younger than he was.

“All he wanted every day was to do the best he could at work,” says director Huston, “and then go right home to his wife. He liked being with Kay best of all. Their joy over the expected baby, which was to be his first child, was shared by every one of us. That he couldn’t have lived to see the child is the greatest tragedy of all.”

At his funeral, all the stars of Hollywood gathered silently to pay tribute. Among the honored guests was the egg man, who delivered two dozen eggs every Saturday morning to the Gable home and had always stopped in to chat. Even his funeral followed the Gable pattern of brevity and simplicity. He used to say, “If anything ever happens to me, don’t let them make a circus out of it.” He had underestimated his world of fans. As in his lifetime, no one would have dared to mar his final dignity and privacy.