1940: Joe Lucky

By J.P. McEvoy

The Saturday Evening Post

May 4, 1940

When Clark Gable revisited New York in the fall of 1936, a mob of hysterical fans surrounded his taxicab and started to rock it. “Come on out!” they screamed. “Come on out, or we’ll turn it over!” The cops rescued him and dragged him to safety.

Down in New Orleans he wasn’t so lucky. A yelling mob of women and girls tore most of his clothes off and made away with his baggage. In Baltimore, a thousand women, waiting at the station, mobbed him. One girl hung on his neck as he dashed from the station to a waiting auto. In Santiago, Chile, he lost everything, including his pajamas. Last summer he wanted to visit the San Francisco World’s Fair but didn’t dare take the risk. The officials offered to close the fair grounds for an hour and let him wander around without danger of being torn to pieces by the mob, who wouldn’t have hesitated to wreck the exhibit in the process.

It wasn’t always thus. The romantic Rhett Butler, who nightly mauls Scarlett O’Hara in 400 theaters for a world’s record gross of $2,000,000 a week, was an awkward, gangling farmer boy with crooked teeth, flapping ears, big shoulders, a microscopic talent, and a pocketful of luck.

“Joe Lucky” is what Clark calls himself, but suspicion grows, on examination of the record, that the biggest part of Gable’s luck is the stubborn determination he inherited from his Pennsylvania-Dutch ancestors, through his father’s family, originally named Goebel, and his mother’s, named Hershelman. If it’s lucky to be Dutch, it’s twice as lucky to be double-Dutch, and Gable drew heavily on his patrimony before he arrived where he is today.

For Gable is not only Public He-Man No.1 but for eight years has been among the first ten box office champions. Today, after trailing many other male stars for high-salary honors, he has pulled ahead with a new contract for $7500 a week for forty weeks a year, for seven years. That ain’t hay, even in Hollywood, and is respectfully called to the attention of a Miss Doerfer, who testified on the stand in Los Angeles that she refused to marry Clark Gable in 1922 because she didn’t think he could support her. Next time, girls, don’t look a gift horse in the teeth.

What is he like, this Clark Gable? Where did he come from? How did he get that way? Oversimplified, the answer to Gable is personality. He would be the first to admit that he can’t emote for sour apples. But he doesn’t have to emote as long as the studio has sense enough to cast him in roles in which he feels comfortable. In other words, roles in which he can be himself, a natural, likable, two-fisted male animal. Occasionally the brass hats up in the front office get delusions of grandeur about Clark, as they did when the put him in “Parnell.” This was the flop heard round the world—a catastrophe that nearly ruined Clark, for in Hollywood it’s a maxim that no matter how good you are, you are no better than your last picture.

Lumberjack Lothario

But Gable’s personality survived, and Gable’s determination kept him going until “Test Pilot” zoomed him back to those rarefied Olympian regions where the Hollywood gods and goddesses loll beside their swimming pools and wistfully read about doings in New York. Only Gable hasn’t a swimming pool, and up to last year didn’t even own a home—just rented one—and, besides that, is one star who honestly admits that he wouldn’t uplift the drama by lending his presence to a New York play. Which reminds me of my friend John Higgenbotham’s classic reply to the Little Theater entrepreneur who was chiding the public for not supporting his efforts to uplift the stage. “My friend, you are suffering from an optical illusion,” said John. “You think you are uplifting the stage, when you are merely depressing the audience.”

Gable came up the hard way. While he was working in the Oklahoma oil fields and Oregon lumber camps as a day laborer, he was developing the fighter’s hands and the wrestler’s shoulders that muscled the sleek-haired Valentino types off the movie screen. The women of America stopped sighing for the tang-dancing Latins and swooned in the shadow embraces of this new lumberjack Lothario, fresh out of the West. Typed first as a villain and later as a hero, he really didn’t hit his best stride until Frank Capra persuaded him to do comedy in “It Happened One Night.” This, as you will recall, glorified love on a bus, which incidentally increased bus travel 43 per cent. Also, as Gable stripped off his shirt and revealed a bare and undeniably healthy torso, a million American men and boys said, “What’s good enough for Gable is good enough for us,” and the undershirt business has never recovered.

But if men stopped wearing undershirts they stated wearing broad-shouldered coats—reversing the current style trend, still influenced by Valentino—for millions of women were now sighing to share the adventures of this dashing he-man, and millions of men were going to look like he-men, even if they had to pad out their thin, round shoulders to create an illusion of virility. Gable got the Academy Award for this tour de force—and has never got it again—even as Rhett Butler, the prize he-man role of stage or screen.

Everyone agreed that Gable deserved all this kudos—everyone, it seems, except the pastor of a church in a little Ohio town, where Gable spent a good part of his boyhood. The congregation of 300 were asked to pray for the conversion of Gable, who, according to their pastor, “….is not good company for our young people—arch-corrupter of youth by demonstrating the art of lust upon the screen,” referring, possibly, to Gable’s missing undershirt. The minister went on to say that Gable, as a boy, liked church and went to Sunday school neatly dressed and “sang in the children’s day exercises in a voice often heard above the others. He was then shy of girls and in his awkward appearance was nothing especially to be desired.”

Later the same year the minister came to Hollywood. Explaining his visit to the fan-magazine writers, the reverend said: “The good women of my congregation have urged me to come here to make a pastoral call on Clark, to pray with him and to exhort him to turn to evangelism.”

Eerie as that sounds, there must have been something in it, for a few weeks later, when Metro producer Irving G. Thalberg announced, he was considering doing “The Knights of the Round Table,” tons of suggestions came in from all over the country nominating Gable for the part of Galahad.

William Clark Gable—the William got lost in the shuffle—was born in 1901 in Cadiz, Ohio. His mother died when he was seven months old, and he was raised by his stepmother. There are no brothers or sisters. But his father is still very much alive in a Hollywood bungalow, where he keeps to himself, loftily ignoring the activities of his famous son. He has yet to visit the studio to watch Clark act. In fact, though he and his famous son are fond friends, he has never approved or understood those queer, wild, acting folks, and when Clark as a young man insisted upon leaving his job as a tool dresser in the Oklahoma oil fiends to go on the stage, his father prophesied no good would come of it. That was his prophecy and he’s hanging onto it with good old Dutch tenacity.

Clark left high school halfway through. “I was casting around for something to light on,” he told me, “and went to work for the Firestone Company, in Akron, molding treads on rubber tires. It was a hot job for a young kid,” says Gable, “but I learned about some of the things that make the world go around, and that you ate through your own physical efforts. I was about eighteen at that time and up to that time had always been on a farm and had never seen night life, and no theater. Now I was running around with a bunch of fellows and naturally went to all the shows, and the first real one I ever saw was ‘The Bird of Paradise.’ I was very much fascinated and made up my mind then I was going to be an actor, so I hung around the theater nights and go acquainted and that way got small parts. I used to want to play character parts. Funny how young men want a costume and a long gray beard. Every week I was a different character. Walk-on bits. Used to walk on with a mop or something. I was paid nothing, and worth every cent of it.”

About this time the postwar depression hit Akron and a new oil boom was on in Oklahoma. Gable’s father gave up farming, went to Oklahoma, and sent for Clark to come down and learn the business. “I was about twenty at that time,” says Gable, “and I worked twelve hours a day learning to be a tool dresser. You have to heat the things to white-hot heat, then two men on each side with sixteen-pound sledges start hammering the face back. There’s a steel gauge, and you have to hammer that back until it fits the gauge perfectly. Then the hole is always round and you get the proper size.

“So I began to learn what made that go. Out there where you’re wildcatting you have to use wood, and we used to bring in great truckloads to keep the steam up. It kept a fellow humpin’. Every twelve hours the tool dresser goes to the top of the well, sixty-five or eighty feet, and greases the crown block. This was usually about midnight, and you go up with your grease can. I want to do a picture about oil sometime. Like the oil wells were at that time.

“All of those things took a while to learn—a long while—particularly with a kid who was not too excited about it to begin with. I was still smelling that grease paint. Well, pretty soon I had seven strings of tools and got twelve dollars a day and paid my own board. I slept in a tent. It was darn good money. Everything you bought down there was about double price. Three or four bucks for a teak, and that in some joint.”

Sock and Buskin

Later, Clark got a job in a refinery. “I got fired off that one,” he mused. A messenger came into his dressing room and said, “Mr. Mayer would like to have you come over to his office when it’s convenient. About going to Atlanta for the opening of ‘Gone with the Wind.’”

“I’ll be over after a while,” said Clark, relaxing. And then to me, “Where was I?”

“You were fired,” I prompted.

“Oh, yes. Well, next I worked on a labor gang. That was in summer, and hot. And you work around those stills that refine oil, which creates a terrific heat inside the still. Every so often we emptied them. There’s a certain amount of deposit, like asphalt, that settles in the bottom of the stills. You have to go in there and take that out. They let the boilers cool for twelve hours. You can stay in there for about two minutes. They time you. In two minutes, if you don’t come out, they come in and drag you out. Then you sit out in the fresh air. In a gang of eight men you start work every sixteen minutes. We cleaned out storage tanks too. You go in with a pick and a shovel and they tie a rope around you. One man would go in at a time. I don’t know how they work it now, but then we’d work until we’d feel faint: it wasn’t very long before you got hysterical. It was a very small manhole—very small. I’ve seen lots of ‘em in there a little hysterical. They’d start to laugh. Then they’d haul ‘em out.

“That was in ’21 or ’22. So I worked at that until I’d saved up a little dough, and my father and I had a little shack at the lower end of town. So I went home one night and said, ‘I think I’m going to leave this time.’ My father said, ‘Stay here. I’ve got all these strings of tools. It’ll pick right up.’ Then he and I tied right into it. I didn’t want to work in the oil fields. I wanted to be an actor. So we parted, not too friendly.”

Gable left the oil industry to the Rockefellers and went to Kansas City, joined a cheap rep company as a general utility man touring the Middle West in tents during the summer, town halls and opera houses in the winter. There were nine or ten in the company. Gable drove stakes, set up seats, valeted the horses and played cornet in the parades. “I don’t know where the star had been, or whether she’d ever played with Sir Beerbohm Tree,” and the tone of his voice showed that Gable was still impressed. “She was a one-eyed woman—lost her eye fencing in a duel on the stage. But I thought she was a wonderful actress. Terrific. They used to do some Shakespeare things in the town hall if there was a university of a good school. The ended up in Butte, Montana, playing things like Are You a Mason?”

“I suppose you had a chance to play different roles?”

“Well, no, not really.”

“Not even a juvenile?”

“No, they said I was too big to be a juvenile. They liked ‘em rather slender and short. So I ended up with the whiskers and all of those things. I don’t think I ever made over twelve or fourteen a week, and as little as two or three. There was no set salary. I washed all the socks and sewed buttons on the costumes. Well, anyway, we blew up in Butte. I had two suits of clothes, an old, tired kit bag my stepmother had given me, a few sticks of grease paint, ties, and a shirt. I couldn’t get an acting job, so I went working in the mines. The piano player was in the same fix. Well, I had no money, so I hocked the bag. There was nothing to carry in it anyway. Bought a suit of overalls, climbed into a freight train in March, and headed for the coast.” [Ten years later he would be voted by the Merchant Tailors’ Designing Association, “America’s Best Dressed Man.”

Clark was on his way to Hollywood, but he was still a long way off. He worked in lumber camps, bummed around on freight trains, and then headed for Portland, where he had heard there was a theatrical job. This was a road company that played the lumber towns. “We folded in Astoria, Oregon, at the mouth of the Columbia River. They were all fisherman, mostly Finnish. We played a week because we couldn’t get out. So we gave up, and I was good and plenty broke again.”

There is a scene in “Gone with the Wind” that makes the women shudder deliciously. Rhett Butler is holding Scarlett O’Hara’s scheming little head in his huge, hairy paws, and is saying, in effect, “I’d like to crush this just like an eggshell.” It is apparent that he could do just that.

Perhaps, girls, you would like to know how he got that way? “So I ceased to act and got a job in the lumber mill. I got a job piling green lumber. All the fellows worked by the foot. They worked hard. They made me work hard too. Probably the toughest work I ever did. The logs were rough, of course, and heavy, and I had no gloves. They all wore leather gloves or a leather palm. I’d tie onto that lumber and it was like grabbing hold of sandpaper. I used to soak my hands; they had cuts in them and would be all stiff and crack open. I’d soak ‘em in salt water and vinegar to toughen ‘em up. Alum, too, that was the stuff. I had hands like a prizefighter until I got my first paycheck and got my gloves, but I didn’t use ‘em before I got my hands all hardened up and toughened. After I’d been there about three months I forgot about the gloves.”

An Ad That Never Saw Print

As soon as he had saved a little money, Clark was back in Portland trying to get an acting job, but his money ran out and he was back in the woods with a brush hook, cutting paths for the surveyors. “You’re a path-finder. You carry all the tools for the engineers—transits or anything. You put ‘em on your shoulders and take off up the mountain with ‘em. Ten hours a day, six days a week, and on Sundays you wash and darn your socks and do your knitting. You didn’t go fishing or anything; you just sat down in the long house with a stove in the middle, with cots one right after another. Everybody slept in them. Your clothes are wet, soaking and steaming, and you can imagine what that’s like. Well, I stayed at that until it was finished. I had no place to spend my money. I’d saved a hundred and twenty-five dollars. That was a lot of money to me, so I went back to Portland, and started looking for a theatrical job.”

No dice, and Clark’s stake was running low again. And now he figured out a scheme for getting a job which was worthy of Dale Carnegie. He went over to the morning Oregonian and talked the editor into letting him work in the want-ad department. If anybody was advertising for a man, he’d know it first. Clark was, and still is, a patient fisherman. He waited six weeks for his first nibble. The telephone company wanted a timekeeper. “That ad never got in the paper,” says Clark. “I just went up and answered the ad and got the job.”

The Dress-Suit Problem

That ad was the turning point of Gable’s life. He worked a year for the telephone company and joined a Little Theater group, coached by Josephine Dillon, who later became his wife. She went to Hollywood and sent for Clark and got him his first movie job, working on a Lubitsch picture with Pola Negri and Rod La Roque. “I worked a few days at that and couldn’t seem to find out what it was all about. I was in a hot uniform, and I held a sword and got five dollars a day.”

There was no rush by the studios to snap up this unique talent, but Louis MacLoon, who was producing plays out in Hollywood, got him a job carrying a spear in Romeo and Juliet, with Jane Cowl, at thirty-five a week. This was more money than he had ever suspected was in the theater and convinced him that at least he was on his way up. He was overoptimistic, for years passed with long waits between jobs, and these only small bits. During the layoffs he hounded the studios, pounded the streets, chased down every clue, but still the movies were not having any. Finally, he got the role of the reporter in Chicago, with Nancy Carroll, and played fourteen weeks in the Music Box on Hollywood Boulevard, right under the movie producers’ noses. Result: Nancy was snapped up for pictures and went on to stardom. Clark went back on the sidewalks.

Occasionally he picked up a job at seven-fifty a day in mob scenes. If he had had a dress suit, he could have gotten ten. One day he heard about a place where you could rent dress suits. So, he took a job as a dress extra at ten dollars a day and hurried over to rent a suit. “How much?” said Clark.

Clark was stunned. This was high finance with a vengeance. “But I only get two-fifty more a day for having a dress suit,” said Clark.

“So what?” said the philanthropist.

A stock company in Texas was looking for a second lead and Gable talked himself into the job. After a few weeks the leading man walked out and Gable inherited his spot. He was making seventy-five a week, but he had never learned the art of studying, and now he had to get up in a new part every week. “I’d go home to the hotel at eleven-thirty at night and sit till three or four in the morning. I’d count the sides—how many pages—and the divide into how many days—and I wouldn’t go to sleep until I’d learned the quota for that day to equalize it. Boy, that was tough. But after seven weeks it got to be easy. So now I thought I was a pretty good actor. I felt it too much. The company closed in May and I came back out here to Hollywood and took another crack at pictures.”

“Still no dice?”

“No go.”

Even Gable by this time began to get the idea that he wasn’t wanted in the movies, so, fortified by his Texas experience, he stormed New York. In a few weeks he was on Broadway, playing The Young Man, in Arthur Hopkins’ production of Machinal. The Telegraph liked “young Clark Gable as the adventurer. He is young, vigorous, and brutally masculine.” The New Yorker thought he was “excellent as the lover,” and The Time volunteered that “Clark Gable likewise played the casual, good-humored lover with a hackneyed gesture.”

Long years passed and many roles were played by Gable in pictures before he had the opportunity to play a good-humored lover again, and when he did (in It Happened One Night, with Claudette Colbert) it was the most sensational success of his career. For here he was relaxed and casual. In fact, both he and Colbert were agreed that it was a silly story and would be a resounding flop, and both of them tried their best to get out of it. Talked into staying by Capra, they decided to kid their way through it, which was the effect that Capra was hoping for. The result was a romp—and a box-office smash.

Machinal was followed by a succession of flips with Belasco, George Cohan, Al Woods, and others, so back to Hollywood went Gable to take another crack at the movies. The movies resisted manfully, but along came the coast company of The Last Mile, and in went Gable. This time he made an impression. Lionel Barrymore came backstage and said, “I’m going to direct a picture and I think I have a spot for you. Will you come out and take a test?” The test was for The Bird of Paradise, the first play Clark had ever seen.

Going Native

“Lionel told Thalberg he wanted to make a test of me as a native, and Thalberg said, ‘All right, take him away.’ So they took me over to the make-up room and, Lionel supervising them, they put very dark make-up all over my body and they curled my hair.” Gable sneered at the recollection. “Then they stuck a hibiscus behind my ear and put a G-string on me and took me down to the stage to make the test. I felt silly, but Lionel was watching and he said, ‘It’s okay. It’s all right.’ Well, he took the test in to Thalberg, who took one look at it and said, ‘Good Lord, Lionel! No, not that. Take it away. Get out! Get out!’

“So I went back to the stage, and then I made a test for Universal and a test for Warners in some of the characters I’d played in stock. They looked at the tests and I went back to the stage, a road show that was playing up the coast. I had a contract for eight weeks, and MacLoon wanted to close after five weeks, but he had me under option to do pictures so we made a deal. I would let him off his three weeks, and he would let me off the option because I had an offer now from Al Woods to go to New York and go into A Farewell to Arms. I was leaving for the train when an agent called me up. ‘Come on out to Pathe,’ he said. ‘Come running.’

“When I got there the agent whispered, ‘It’s a Western,’ and the director said, ‘Do you ride?’ But he didn’t say what, so I said sure. ‘Well, that’s fine,’ he said. ‘We aren’t quite ready yet, but we’ll start you on salary right now and notify you when we want you.’ That was my first jolt. I’d been used to rehearsing three or four weeks without a salary.

The Man on Horseback

“Outside, the agent asked me, ‘Can you ride a horse?” And I said, ‘I haven’t been on a horse since I was a kid.’ And he said, “How do you think you’re going to play a hero in a Western if you can’t ride a horse? You better get busy and learn.’ So I hunted up a riding academy and found a cowboy and hired him for two hours a day to teach me to ride. It was five weeks before they began the picture. By that time, I could ride, but good. We went to Arizona, and the first day I was on that horse from nine in the morning till lunch, and I got back on him and rode till six. Seventeen weeks at seven hundred and fifty dollars a week. I was a rich man, ready to retire.”

He never got the chance. Metro gave him a part in The Easiest Way in 1930, and, before the picture was finished, put him under contract to the studio and never let him get away. His fame skyrocketed; his salary jumped. A new star was born—a new type of hero who could project through the pink icing of Hollywood glamour the natural devil-may-care- of a Middle West farmer boy, factory hand, oil-well driller, miner, bum, lumberjack and stock actor.

That is the Gable saga as he tells it himself. There are gaps, just as there are in the official biographies handed out by the studio. Only a brief mention of Josephine Dillon, the dramatic coach who married Gable fresh out of a lumber camp and taught him how to sit and stand and walk. Four years of this and the partnership dissolved. Three years later Clark married a Mrs. Langham, ten years his senior. This last eight years, and Clark paid her $286,000 plus taxes for a release. Parting is such sweet sorrow.

Free once more and acting in Gone with the Wind, Clark waited for a day off and then eloped with Carole Lombard (nee Jane Peters) to Kingman, Arizona, just a year ago this March, accompanied only by Otto Winkler, of the Metro publicity staff, who drove them there and back in his own car. Gable gave his age as thirty-eight, Carole, thirty-one. All the press services and newspaper-column gossipers, who had been watching the romance of these two like so many hawks, were completely outfoxed. So was the lone reporter for the Kingman paper. He was crossing the street when the Gable-Lombard car came around the corner and almost nipped him. He turned to tell them off, and for a moment the elopers thought they would be discovered before they could be married and get away. But the reporter didn’t recognize them and missed the biggest scoop he’ll probably ever have in his career.

Driving back the same day, the couple headed for home and filed their honeymoon under Pending. Home is a twenty-acre ranch in the San Fernando Valley, about forty minutes’ drive from the studio. The ranch house, garages, stables and poultry coops are simple but expensively comfortable. The fruit trees are pruned, sprayed and massaged personally by Clark, who took me around and introduced me to each one separately, referring now and then to the tags identifying them, since all Clark’s farming experience was of the Ohio variety and how should he know from lemons, grapefruit and avocados?

“What do you do with the fruit?” I asked him.

“I give it away,” he said. “You can’t sell it, and even if I could, I wouldn’t get back anything like what it costs to raise. Why, when my farmer brought me the bill for irrigation last month I said to him, ‘What are you using on those orange trees—mineral water?’”

We walked around to the tool shed. Every known gadget for scientific farming was there, slick and shiny.

“This is my pet,” said Clark, and he patted an odd-looking contraption. “Whenever I have a spare moment, I come out and use this.” I wondered what it did. “It whitewashes,” said Clark. “It sprays whitewash on tree trunks, fence posts, anything you like. I’ve whitewashed everything around here but Carole.”

Back in the house we sat in the gun room and Clark rang for drinks. A man staggered in with two of the biggest Scotch highballs I’ve ever seen. “Have a little snort,” said Clark. “Carole will be down in a minute.”

We snorted and chatted. What were his plans for the future? “To keep going until they catch onto me.” How about knocking off sometime and doing a play? “Well, if I found one that was fun and didn’t show me up. I have no illusions about my acting.” Wasn’t he acting now, as Rhett Butler? “I have very little to do, as a matter of fact. Practically a stooge.” How did he happen to go in for farming instead of horse racing, like his neighbor, Bing Crosby, for example? “Because I farmed as a boy, I guess.” Did he like it then? “No. Hated it.”

“’The typical successful American businessman,’ said the late Don Marquis, ‘was born in the country, where he worked like hell so he could live in the city, where he worked like hell so he could live in the country.’”

The Fabulous Farmers

“That’s about the size of it,” said Clark. “Silly, isn’t it? Except for an occasional hunting or fishing trip, I spend all my time out here. And yet, as much as I enjoy this place, the farmer who works for me gets more good out of it.”

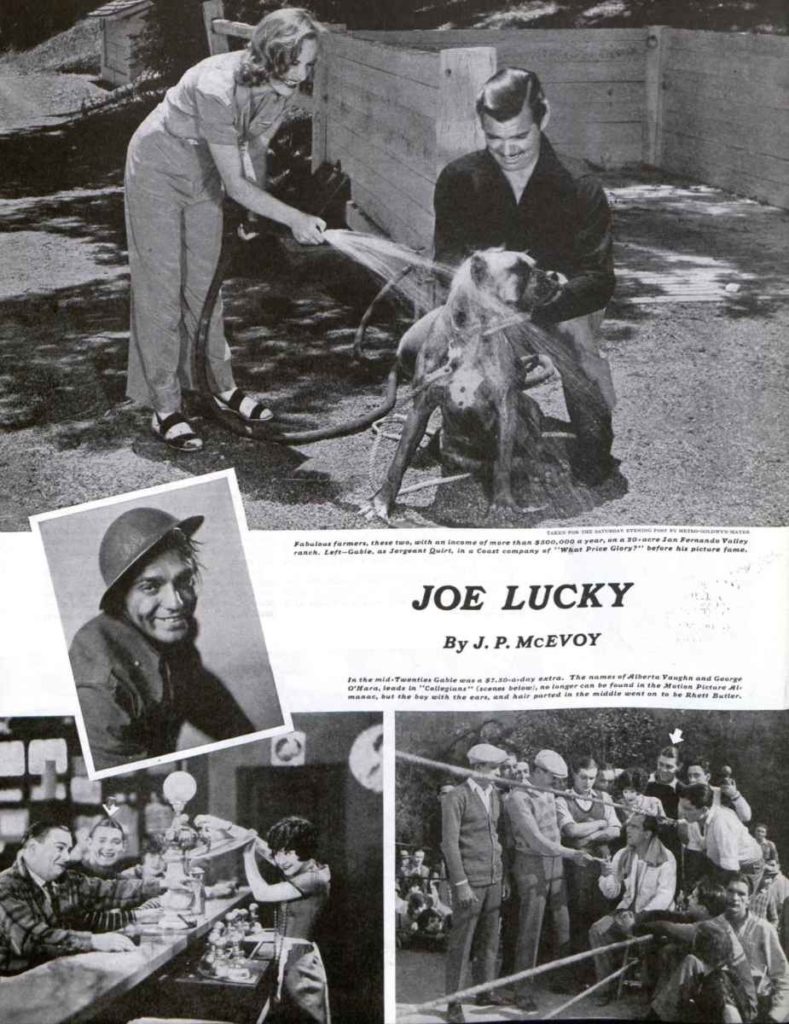

Fabulous farmers, these two—Clark Gable and Carole Lombard, with a total income of more than half a million a year and nothing to do with it but support a small citrus grove with what’s left after Uncle Whiskers takes 60 or 70 percent of it. Entertain? Not in the legendary Hollywood manner. A few intimate friends at home, yes; but the night clubs never see them. What does Clark do with his money? Well, he’s Dutch and thrifty and doesn’t need an elephant’s memory to recall how it feels to be broke and hungry, so he chances are very good that he goes down a hole with it every week, like a chipmunk. It takes a special kind of vigilance, anyway, to hold onto movie money, for it is a kind of cheese which a thousand varieties of Hollywood mice are always nibbling at. The agent takes the first good bite—10 percent of the gross—in Clark’s case, a neat 750 bucks a week. Incidentally, it is interesting to note in this connection that Clark’s present agent, Phil Berg, bought his contract from another agent a few years ago for $15,000, or the equivalent of twenty weeks’ present take. For Gable makes as much in ten weeks as the President of the United States collects in a year, which is decidedly unfair, since Roosevelt is a much better actor. Unfortunately for FDR, he hasn’t got a Hollywood agent.

When “Gabriel” Arrived

Agents, press agents, bodyguards, trainers, chauffeurs, butlers, valets, gardeners, and lawyers—to name only a few. Stars are always paying off rather than be annoyed or injured by adverse publicity, even though undeserved. Occasionally, though, they fight back, as Gable did when Violet Norton came to town, spoke of Gable as her “flymin’ love” and pointed to a buxom lass as the fruit of their grand passion.

Gable got sore and insisted on a court trial.

The lady from Essex stuck to her story: Clark Gable was Frank Billings. He had wooed and won her while he was acting in England. Gable had never been in England, and proved it t everyone’s satisfaction, including the court’s—but that was Violet’s story, and it finally stuck her. Upon being convicted of illegally using the mails in an attempt to defraud, she passed out of the picture in a shower of headlines.

Gable unquestionably is dynamite with the femme trade, as Variety would tastefully put it. When he flew to Atlanta by special plane for the opening of Gone with the Wind, the governor of Georgia declared it a state holiday, and the seven-mile route from the airport to the hotel was packed solid, mostly with hysterical women trying to climb into Gable’s car and take a nose or an ear for a souvenir. The theater had 2,000 seats, but there were 40,000 requests for tickets for the premiere. Metro avoided a new battle of Atlanta by handing the tickets over to the local Community Chest and letting them pass out the troublemaking pasteboards at ten bucks a piece. The local Junior League girls sold 8,000 tickets at ten dollars apiece for a dance, because Clark Gable was appearing in person and might, if luck was with them, dance with one of them. The story that he had graciously agreed to come to Atlanta crowded everything else off the front pages, and one newsboy ran through the streets waving the big black headline and shouting, “Gabriel’s coming!”

Bit the Gable fan who achieved an all-time high for something or other was the quit, middle-aged lady who walked up to the room clerk in the Atlanta hotel where Gable was stopping.

“When is Mr. Gable checking out?” she inquired reverently.

“Saturday midnight,” said the clerk.

“I want to reserve the same suite,” said the lady. “And I want to move in as soon as he leaves.”

“Very well,” said the clerk.

“And I want everything left just the way he left it,” said the lady, with shining eyes.

The clerk hesitated. “But we’ll have to—”

“No,” breathed the lady. “Don’t make the bed!”