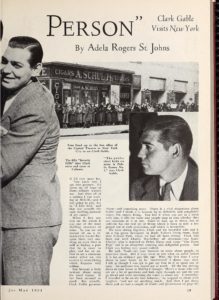

1934: In Person: Clark Gable Visits New York

By Adela Rogers St. Johns

Silver Screen, May 1934

Clark Gable sees so many women

He’s crazy about horses

Wherever I go people say, “Do you know Clark Gable?”

I say, “Sure.”

“What’s he like—really?”

I’ve decided in view of all I owe Clark Gable—who gave me one of the most thrilling moments since I was born—to let you in on a secret. I mean, after all, what’s the use of keeping things to yourself all your life? The truth is that Clark Gable is the most attractive man off the screen that we’ve ever had on the screen—maybe that sounds a little involved, but you know what I mean.

It just happens, because of the way we met and the things that happened, that Clark and I are friends. He is a man capable of friendships—real friendships. That word friend means so much to me that I use it very rarely. Life offers few things more splendid than friendship, as most of us know, and so I’d like to tell you the story of a funny thing that happened because I think it’s rather nice.

Several years ago I wrote a book called “A Free Soul.” It was very close to my heart, that book, and for ten long months I spent a good many hours every day, trying to write it to the very limits of my ability, whatever that may be. Maybe you don’t know it, but sometimes writers pour into their work everything they possess, every feeling they have. And the people in that book become very, very real to them.

The hero of “A Free Soul” was a young man named Ace Wilfong and, though I started out to write a story about a girl and her father, somehow Ace grew more important as the book progressed, until I felt I knew him very well indeed—that he was someone real, and that I wished I had him for a friend. I used to think about him a good deal and wonder if there was anyone like Ace around anywhere.

Well, the book was finished, and it ran in “Cosmopolitan” as a serial, and it was a best seller, and as a play it ran on Broadway for quite a while, and then they decided to make a motion picture of it.

Naturally I wondered a lot about who would play Ave. The young man who had played it on the stage was very good—but he wasn’t my Ace. Oh, not at all. And I somehow felt that it would just break my heart if in the picture I didn’t see the real Ace.

Now, one day I was walking across the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer lot, and upon the flower-bordered walk I came face to face with a tall, dark young man, who swung along with a trace of swagger in his walk—a young man who smiled at me as we passed. He had blue-gray eyes in a dark face, and a crest of black hair, and the figure of a guardsman. And when he had passed, I stopped suddenly on the path and said aloud to myself, “Why—that was Ace.”

I followed him then, quite shamelessly, and discovered that he was a comparatively unknown young actor named Clark Gable. So, it being strictly none of my business, I flew up to Irving Thalberg, the genius of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer, and said, “I’ve just seen a man named Clark Gable—”

Irving twinkled at me. “And you want him to play Ace Wilfong,” he said. “Well, don’t get excited, he’s going to.”

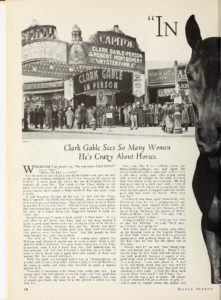

The other night I was dining with Clark in his dressing room at the Capitol Theatre in New York, where he was making personal appearances and packing them in. And, for the first time, he told me the other side of the story.

“Funny, isn’t it?” he said, “how things happen, and people drift together. When I was on the stage in New York and not doing too well—probably because I wasn’t a very good stage actor at best—I read “A Free Soul” in a magazine. I was nuts about it. I used to sit and think about that guy Ace and I’d say to myself, ‘I’d rather play that part than anything I ever read.’ I read the darn book two or three times until I felt I knew Ace—well, like he was a pal of mine. Of course, I never dreamed I’d get a chance to play it—and I used to wonder about the author and if I’d ever meet her.

“You know how I got into pictures. I’d given up all hope of them—nobody wanted me. And then all of a sudden I was working at MGM, and I was going to play Ace in ‘A Free Soul,’ and that was actually the most thrilling moment of my career.”

When I first saw him on the screen it was one of the most thrilling moments of mine. So you can see we started off on a remarkable basis—because there isn’t anything an actor likes as well as finding a part that he is crazy to play, and for an author to see a character come alive on the screen is something which happens very seldom.

You become a little hesitant about using the word charm. It has been misused so much. But actually, Clark Gable possesses charm—and something more. There is a vital magnetism about Gable—and I think it is because he so definitely and completely enjoys life, enjoys living. You feel it when you are in a room with him, it fills the room and people turn to him where they are conscious of it or not. Good or bad, up or down, hot or cold—he has the real joy of living which is born in only a few people out of each generation, and which is irresistible

We were sitting together, Clark and his beautiful wife and I, on a big green davenport in Rudy Vallee’s living room, high over Central Park, where we had all been dining. Clark had been out with Charlie MacArthur all afternoon—you know Charlie, who is married to Helen Hayes and wrote “The Front Page” and is an altogether amusing and delightful person. And Clark was feeling very grand indeed.

He said, “Look—it’s your business to write about people, to interview them. Did it ever occur to you what an awful ordeal it is for an ordinary guy like me? Why, the first time I came down to your house to be ‘interviewed’ I damn near died. I felt as though I was apt to put my foot in it or speak out of turn. No audience ever scared me as much. All the day driving down to your house at Malibu I thought, ‘Here’s a dame who will ask me a lot of questions and look right through me and she can go ahead and write anything she want to about me.’ I remember I intended to be on my best behavior,” he stopped to shout with laughter, “and not say anything much. And then I got down there and we had a couple of drinks and talked about everything but me.”

Let’s see what I can honestly write about Clark Gable now that, after four years, I do know him well.

When we were all on a weekend party at a big California ranch, I noticed one thing about Clark. He was very sociable, and he made everybody laugh, but after about so long he would suddenly vanish and be gone for hours. Being naturally curious, that intrigued me. I soon found out where he went. He took a horse and rose—rode for miles into the hills, rode by himself and came back hot and dusty and tired and very happy.

No one I ever met keeps so boyish a quality. I mean, Clark is not a kid. But he enjoys himself wherever he may be with all the fervor and vitality of a college freshman. It’s a very endearing quality. I have never yet seen Clark bored. I remember one night we were at a rather dull dinner party in Hollywood. Since I name no names I can be honest and say it was one of the dullest dinner parties I have ever attended. There were a lot of important people present, and they were all busy being important, and they didn’t say much that was interesting because evidently they were afraid somebody would steal an idea. That happens in Hollywood. After dinner, Clark was again missing. We found him upstairs in the playroom, running the electric train for the small son of the house and having the time of his life.

On his recent trip to New York—his first in four years, and the first time he has been on Broadway since he made his big hit—he enjoyed himself with the same simplicity that you would expect of an out-of-town buyer from Syracuse. There wasn’t any pretense about it. He got a kick out of the nightclubs. He got a thrill out of every play he saw. Coming out of the Capitol with him one night after the show—he had maneuvered a secret way through the cellar do that he didn’t have to be torn to bits nightly by the girls who waited outside the stage entrance—we were instantly hailed by a taxi driver, whose name, it appeared, was Tony. Tony waited for him in that particular spot every night and took him back to the hotel. The first thing Tony said was, “Well, Clark, how’d the show go today?” And they discussed it all the way back to the Waldorf.

It is literally impossible to make Clark Gable take anything seriously. Anything. He likes his work, but it is impossible for him to regard it as something sacred, as something the world just couldn’t get along without. He thinks it’s fun—especially pictures like “Hell Divers.”

But, in the confidences of his friends, he will comment upon certain of his own performances with ribald and biting criticism. There is one in particular, sometime in the past, which causes him most unseemly mirth. “Probably,” he will say, with his irresistible grin, “the worst performance ever given on stage or screen. But, you must admit I was miscast.”

On the other hand, he will be boyishly proud and pat himself on the back with glee over something he has done which he really thinks is good. “I knocked that one dead,” he will say.

His stay in New York was slightly hectic. Not since the days of Valentino was anyone so besieged by adoring crowds of young ladies. They clustered about the stage door, they waited in the hotel lobby, they followed him wherever he went. He was gracious—he had a lot of fun out of it. Someone said to him one day, “Oh, isn’t it awful—I should think you’d be worn out with it all.”

Clark grinned pleasantly. “Look,” he said, “the day they stop wanting my autograph I’m through. And I know it. It takes a little time but I think I’m pretty lucky. After all, why the deuce should they want my name scrawled on a piece of paper unless they really like me?”

Clark enjoys his fame, enjoys his popularity, as he enjoys most everything. The only thing he really dislikes is being misunderstood.

“Hell, I don’t kid anybody,” he told me, when some paper had printed something about him that was untrue. “I put it right out there on the line. But it’s gotten so that the public press makes everyone think you’re always playing for publicity. That’s hardly fair. Is it? Sure, I go and hunt deer up in the California mountains. I love it. Sure, I buy myself a race horse and see him run down at Caliente. That’s one of the kicks I get out life. But there’s been so much printed that wasn’t true, that the first thing you know they don’t believe anything—they don’t think you’re on the level at all. And do you know, it’s funny—” for a moment his face was quite serious, his eyes that are so amazingly blue under the heavy black brows looked very straight at me, “It’s funny, but I like people to know that what I do is just what I would do if I’d never been on the screen. I’d like them to know I am just what I am. People have been very good to me and I’d hate to have them think I was kidding them about anything.”

As a matter of fact, there is absolutely no pretense about Clark. I would say that the only thing he does, because he is a screen star, which he wouldn’t do otherwise is to keep dressed up occasionally. His ideal costume is a pair of old cords and a sweatshirt and he doesn’t really care much about clothes.

Perhaps one of the most fortunate things in Clark’s life is his marriage. Ria Gable is a woman in a thousand—a lady who knows the world, who is a charming hostess, who understands Clark Gable as no one else ever can. She fits herself into his life, she makes his life a thing of ease and comfort, she takes things as they come. Everyone likes her—there isn’t a more popular woman in Hollywood and, in confidence, that is not always true of the wives of popular actors.

“I wish,” Clark said the other night, “you’d write me another story. And give me a good lusty heavy to play. You know, I like to play heavies—nice, likeable, violent heavies. That’s my ideal.”

He means it, as the studio can tell you.

Do you ever stop to think about the people you know, and wonder, if you were in a bad jam, just which one of them you could turn to? Do you ever wonder which one of them would help you out, without making it too tough, and would know how to do it in the simplest possible way, without hurting you, with good clear common sense—and make you feel you had really done them a favor in asking for help?

I think most of us get in jams now and gain and no matter how many friends we have, we do stop to think of all that.

Well, of all the men I know, and in my job, I have to know a lot of them, I think I’d rather have Clark Gable with me in a pinch than anyone I can think of.

If he liked you, if he was your friend, he wouldn’t ask any questions, he wouldn’t lecture you, and he wouldn’t make any mistakes.

And there is another thing about him as a friend that is rare. If you don’t see him for months, you pick the thing up just where you left it.

I don’t know whether you feel about this as I do or not—but I rather imagine you do. It’s always a real happiness to me to feel that people I admire are worthy of it. I hate having my illusions destroyed. I don’t like to find out that somebody who is thrilling on the screen is a mess off. I hate to think that a man who gives the feeling of strength and manliness and joy of living that Clark Gable does is really pretty much of a weak sister or a nuisance off.

I’ve known Clark Gable pretty well for a long time now.

The secret I wanted to tell you is that I’ve had a chance to prove him—and he is even nicer, he is even more Clark Gable “in person” than he is when he’s playing the most heroic role. I hope you’re as pleased about that as I am.