1947: The Gable I Know

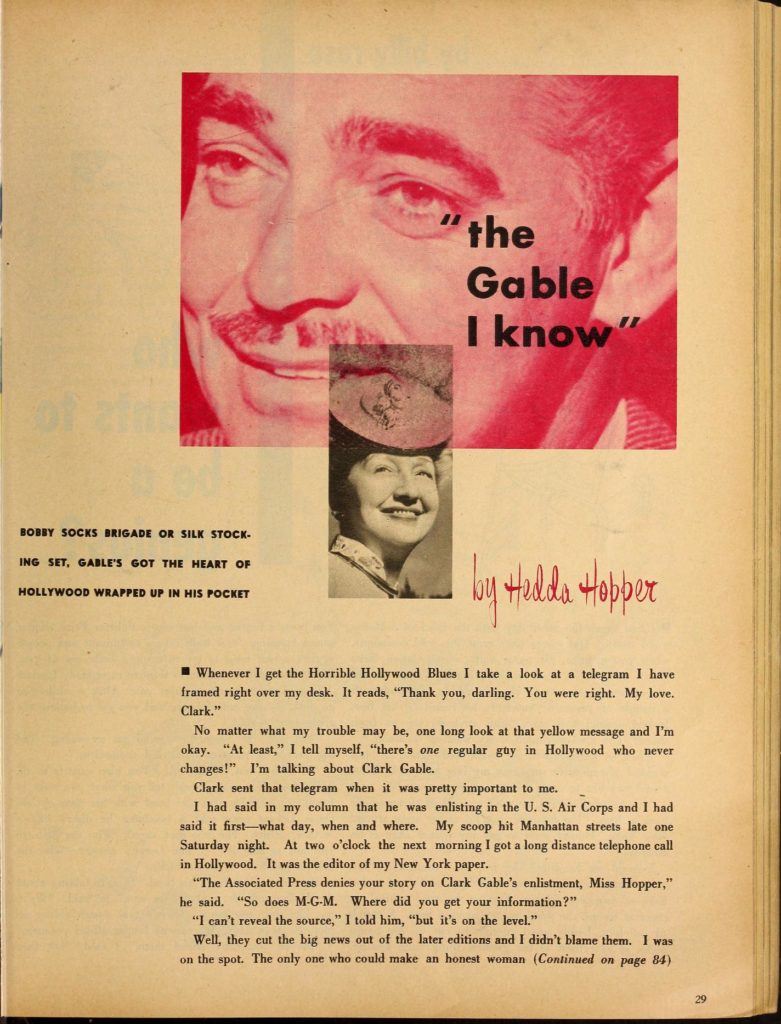

The Gable I Know

By Hedda Hopper

Modern Screen, March 1947

Bobby socks brigade or silk stocking set, Gable’s got the heart of Hollywood wrapped up in his pocket

Whenever I get the Horrible Hollywood Blues I take a look at a telegram I have framed right over my desk. It reads, “Thank you, darling. You were right. My love, Clark.”

No matter what my trouble may be, one long look at that yellow message and I’m okay. “At least,” I tell myself, “there’s one regular guy in Hollywood who never changes!” I’m talking about Clark Gable.

Clark sent that telegram when it was pretty important to me.

I had said in my column that he was enlisting in the US Air Corps and I had said it first—what day, when and where. My scoop hit Manhattan streets late one Saturday night. At two o’clock the next morning I got a long-distance telephone call in Hollywood. It was the editor of my New York paper.

“The Associated Press denies your story on Clark Gable’s enlistment, Miss Hopper,” he said, “So does MGM. Where did you get your information?”

“I can’t reveal my source,” I told him, “but it’s on the level.”

Well, they cut the big news out of the later editions and I didn’t blame them. I was on the spot. The only one who could make an honest woman out of me was Clark Gable.

That’s when I got his telegram, “Thank you, darling. You were right…” No reporter could ask for better backing-up. But I didn’t have to ask Clark—that’s the point. It was his own idea and maybe you think I don’t love him for it!

The first time I fell for Gable all I saw was his back! I was sitting twelfth row center at a Broadway play called “Machinal.” Although I leaned in my seat and craned my neck like a hick I never did see his face. Just his back. But that was enough. It had strength and vigor and the comforting maleness that women adore.

“Who is that?” I whispered to my companion. He peered at his program. “Let’s see—it says, ‘Clark Gable.’ Never heard of him.”

“Neither have I,” I sighed, “but you can wrap him up and send him over!”

Hollywood took care of that. Soon afterwards I was acting on a picture set right beside the glamor-back guy.

Clark played a laundry truck driver in that picture. Me, I was a sassy baggage, as usual. Neither of us was a star. In fact, we were both VUP’s—Very UNimportant People—then. But the star was a VIP—definitely! And did she know it! She didn’t deign to speak to the rest of the cast.

Pretty soon Clark got disgusted. One day when Miss Temperament sashayed by without even a nod, he raised his black eyebrows and then gave him a puzzled knit. “Say,” he asked me, “what’s eating her, anyway?”

“A common Hollywood affliction,” I cracked. “’Big-head’ we called it back in Altoona.”

Clark whistled and shook his head. “If that ever happens to me,” he said, “I hope somebody kicks me right out of town!”

Janet Gaynor told me a story once about Clark that’s typical of another facet of his personality. It happened back in the days when he was an extra.

So was Janet. Janet came to work on the bus, but Clark was slightly grander. He owned an old broken-down, rickety flivver. One night Clark saw Janet trudging along after work, as he rattled his flivver out the gate. “Hop in,” he smiled. “I’ll take you home,” Clark offered gallantly. “Where do you live?” Janet told him, and they chugged away in that direction. Neither said much because they didn’t really know each other. That’s why Janet thought it was so funny when Clark pulled up at the curb, halfway home, said, “Well, see you later,” and ambled off, leaving the jalopy parked there!

It wasn’t until years later that Janet learned why her ride had ended so abruptly. She and Clark were both big stars by then. They met at a party and got to laughing about their hungry extra days. Janet remembered that puzzling ride and asked Clark right out why he’d ditched her half way home.

“I always felt bad about that,” Clark grinned. “I ran out of gas. I didn’t have a dime to buy any more either. And I was just too embarrassed to admit it!”

No one could have been nicer to his coworkers than Clark. One day I was on the set of Jean Harlow’s picture, “Red Headed Woman.” It was just another picture for Clark. He already was Mister Hollywood then, as he is now. Jean had made “Hell’s Angels” and proved a one-picture sensation. She was anxious to come through again and very nervous about it.

When I arrived, Jean was in tears. She’d been blowing take after take in her nervousness. The director was at his wits end. After spoiling another take, Jean finally gave up and ran to her dressing room. Clark followed her, put his arm around her like a big brother and I heard him say: “Listen, honey, that’s just a little bit of film running through a camera. It doesn’t amount to a hill of beans. They’ve got plenty more, so take your time and don’t be nervous. Let’s try it again,” he grinned, “while we’re all worked up, hot and bothered.” Jean laughed and the ice was broken. He’s as comforting as a doctor when he wants to be. On the other hand, if you’re gone on him, Gable in the flesh can be very upsetting.

I’m thinking of Judy Garland, who toted a teenage torch for Clark that was a lulu. Clark was her god. That’s why Judy got such a thrill when Roger Eden wrote that song for her to sing at am MGM exhibitor’s convention in Hollywood. You remember—“Please, Mister Gable?”

I happened to be lunching on the MGM lot with Clark when he got the idea he’d like to meet Judy and hear that song in person. “Come on,” he grinned. “Let’s go over to Judy Garland’s set and say hello.”

Clark walked in, beamed his most charming smile and draped his arm down over the canvas chair that said, “Judy Garland.” Judy was in it and her eyes opened up as wide as saucers.

“Judy,” Clark pleased in his most persuasive voice, “will you sing my song for me?” Judy didn’t answer, she couldn’t. The crew gathered around sensing an occasion and Judy, little trouper that she was, climbed up on a table, a piano player twirled his stool and she went into “Please Mister Gable,” singing right to Clark. She sang it as she never had before because Judy Garland was singing to a very special audience.

When she was through, Clark stepped up, lifted her down and gave her a great big kiss. “Thanks, honey,” he smiled. “That was a real thrill.”

I always admired the way he stuck up for Lew Ayres when all Hollywood was yelling for Lew’s scalp. Most of his old friends turned their backs when Lew turned “Conshie.” Lew’s back now with added stature as a man and an actor. But there weren’t many who cheered him in democracy-prating Hollywood then. One of the few who did was Clark Gable.

In the midst of the hub-bub, Clark went to see Lew, and said: “Remember, this America, and you’ve got a right to your convictions. If I can do anything to back you up, let me know.”

I don’t know anyone in Hollywood who’s ever been a good friend of Clark’s who still isn’t. And that includes both his first two wives. I know them both, Josephine Dillon and Rhea Gable. I’ve never heard them run Clark down in any department; I’ve never heard him say anything but the best about them. Jo Dillon taught Clark how to act and Rhea, a wealthy society woman, gave him polish and social poise. Clark was and still is grateful for both. In both cases he parted friends. Clark was particularly fond of Rhea’s children and they adored him and still do. I’ve always thought it a downright shame that in three marriages Clark Gable never had any children of his own. He’s a frustrated father if I ever saw one.

Even all during the war, when he was in Europe and busy with a dozen duties in a topsy-turvy world, Clark never forgot the birthdays of the Goff kids, children of his best Hollywood pal and fishing companion, “Tuffy” Goff, who comes at you over the radio as “Lum” of “Lum n’ Abner.” For every birthday and Christmas, too, a present came winging across the Atlantic from London, or wherever Clark was.

Clark has always yearned and reached for the realities of life to compensate for his artificial existence as a movie star. That’s the reason he just had to go to war—even though he was over-age.

When Clark enlisted, he wanted to sever all his Hollywood ties. The break in his life, occasioned by the tragic death of Carole Lombard, made him want to leave everything behind.

I recall pleading with him not to sell his ranch. “You’ll regret it,” I warned. “You’ll need a place to come home to, a place to think about while you’re away. Save that for the future.”

Clark gave me a dusty look, as if to say, “What future?” And maybe that’s the way he felt then in his sorrow. But I know he was mighty glad he had a home when he came back to Hollywood and he was glad to get back to Hollywood. Just as Hollywood was mighty glad to have him. The King was still King.

I know how much to heart Clark took his war duty and how hard he tried. If there’s anything, for instance, that makes Clark die inside it’s making a speech. But when they picked him to make the graduation speech at his Officers’ School, he did it. And he came up with one of the best speeches ever made—so good it was circulated through the Air Corps.

I know, too, how hard Clark worked—night and day with his writer pal, John Lee Mahin—to make his Air Force combat movie. It was easily the greatest disappointment in his life that another combat movie beat his to the punch and his labor of love ended up in a film vault.

Clark has always looked more lightly on his Hollywood career.

I remember in one picture, years ago, Clark played a scene where a bulldog chased him and nipped off the seat of his pants. It’s pretty hard for a director to tell a bulldog just how far to go and this one went too far. He took some of Clark’s skin, too, and they sent Clark to the hospital. I sent Clark a note, “What have you got, anyway? Even bulldogs can’t resist you!”

Well, right after that, death, as it must to all dogs, came to this bowser. I’m sure it had nothing to do with the Gable diet, but Clark thought the joke was on him, and it was. He sent me a wire. “The ham was just too tough!”

He still grins at his own romantic screen illusion. He was making a scene in “Adventure” where he chased Greer Garson up a steep hill and caught her just at the top. They’d been having technical trouble with the takes and Clark did it three times. At the end of the third, he puffed like a porpoise and mopped his face. A prop man dragged up a chair. “Here,” he said, “sit down, Clark.”

“Let’s face it,” Clark grinned. “What I need is Lionel Barrymore’s wheelchair!”

He may kid about himself, but he’s a conscientious workman. I popped in on “Adventure” one day around quitting time. I got my usual “Hello, darling, how are you?” and a great big Gable hug. But I got the brush-off, too, after that—until Clark was through with his job.

It was almost five o’clock. The rest of the cast were due to quit anyway in a few minutes. “Go on home, Clark,” said the assistant director, glancing at his watch. “We can kill this set tomorrow.”

“Let’s kill it tonight,” said Clark, “then we can all have a drink.” I had to wait a spell to have my cocktail with him. But I’ve never minded waiting for Gable. Who would?

What Clark wants out of life is about the same as it was before he left Hollywood for the ar. Only now it is the time, he figures, to do it—before, as he grins, “I fall apart at the seams.” He’s got a hunting trip to Wyoming on the sheet, a fishing one, in Oregon. He’s got a Sun Valley trip planned this winter, and another jaunt East to New York for the shows and some city life. He’s been collecting dope on Central America and Alaska, too; object—big game shooting. He’s started digging a swimming pool on his ranch. And now, too, he’s definitely set to do Frederick Wakeman’s “The Hucksters.”

He wants to catch up with himself and follow as much as he can the kind of life he and Carole Lombard had planned before, but by himself.

I don’t think Clark will ever get married again until he finds a girl who can do for him what Carole Lombard did—be his pal.

I was ragging Clark just recently about a romance rumor, and I should have known better. But the Eastern papers were full of Clark and a New York society woman. When he came back to Hollywood, I collared him. “Honey,” I said, “What’s all this about, anyway? Are you going to marry the girl?”

Clark shot me an annoyed “come-off-it-Hopper” look. “Now listen, Hedda,” he said. “I’ll ask you a question: Can you imagine So-and-so (and he named her) leading a pack horse?”

Clark Gable’s happiest days were the short years of his marriage with Carole Lombard. She loved life and she’d want Clark to get all the fun that’s coming to him out of his.

Clark can’t look at a woman without a marriage rumor. I suppose in his Hollywood career, Clark has had his name linked with as many women as Errol Flynn. But there’s a difference. In Clark’s case, there has never been one drop of scandal.

In fact, the only scandal I know about my old friend Clark Gable is an item I doubt if even Clark himself knows. I’ll just have to tell it on him before I let him off the hook, so he won’t look too much like a saint.

There was a little girl in Hollywood, the daughter of a producer, who trotted off to a movie matinee one Saturday afternoon. Her mother thought she was going to see a Walt Disney Silly Symphony—obviously harmless—and when she came home they asked her how she liked it.

“Fine,” said the little girl. “Norma Shearer’s so pretty!”

They didn’t get it. What was Norma Shearer doing in a Disney movie? They questioned the child and found she’d seen the burning adult drama “A Free Soul” with Shearer and Gable instead.

But the kid had another question. “Mother,” she asked, “is Norma Shearer sick?”

They said no—what made her think so?

“She must be,” insisted the tot. “Because in the picture she was lying down all the time!”

That set the producer and his wife to thinking—and talking—and that’s when the Hays office was born. So I guess that makes Clark Gable the first real swoon king whether he knows it or not. For my money, he always will be.