1935: Into a White Hell for You

By Jack Smalley

Hollywood, June 1935

Loretta Young and Clark Gable had never faced such hardships as they endured upon this amazing journey

As you movie goers sit back in a comfortable seat in your favorite theatre, do you ever think of the hardships—sometimes almost incredible hardships—that a group of film workers suffered to make your possible entertainment?

When 20th Century’s Call of the Wild company left the studio, they planned to be gone ten days or two weeks. But they reckoned without the frigid grasp of a northern winter. Held by the icy blasts of blizzard after blizzard, the weeks lengthened into more than a month of privations from cold and threatened starvation.

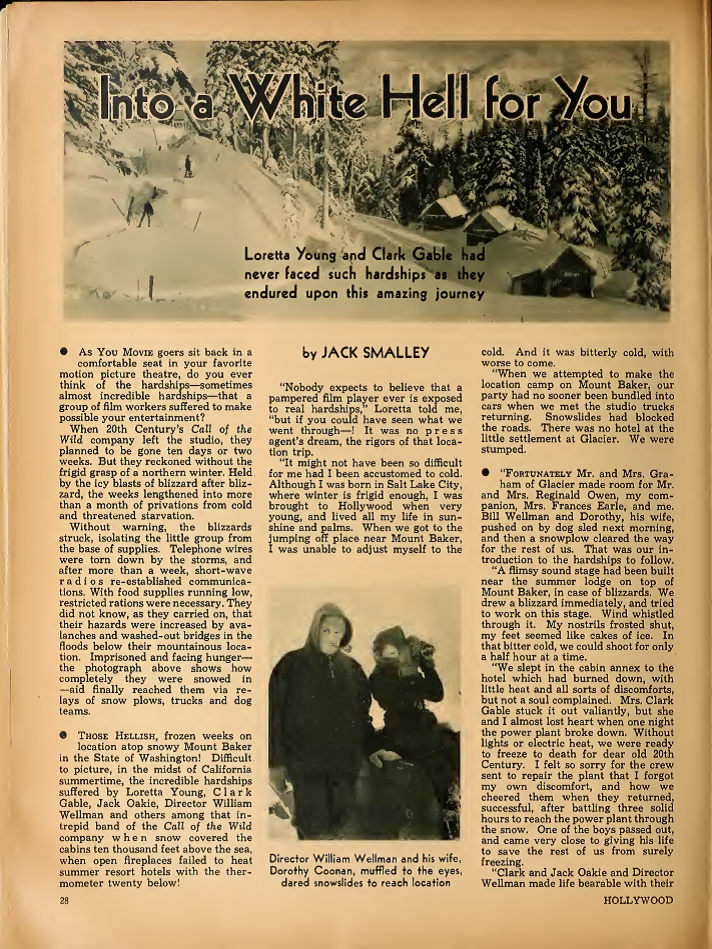

Without warning, the blizzards struck, isolating the little group from the base of supplies. Telephone wires were torn down by the storms, and after more than a week, short-wave radios re-established communications. With food supplies running low, restricted rations were necessary. They did not know, as they carried on, that their hazards were increased by avalanches and washed-out bridges in the floods below their mountainous location. Imprisoned and facing hunger—the photograph above shows how completely they were snowed in—aid finally reached them via relays of snow plows, trucks and dog teams.

Those hellish, frozen weeks on location atop snowy Mount Baker in the State of Washington! Difficult to picture, in the midst of California summertime, the incredible hardships suffered by Loretta Young, Clark Gable, Jack Oakie, Director William Wellman and others among that intrepid band of the Call of the Wild company when snow covered the cabins ten thousand feet above the sea, when open fireplaces failed to heat summer resort hotels with the thermometer twenty below!

“Nobody expects to believe that a pampered film player ever is exposed to real hardships,” Loretta told me, “but if you could have seen what we went through–! It was no press agent’s dream, the rigors of that location trip.

“It might not have been so difficult for me had I been accustomed to cold. Although I was born in Salt Lake City, where winter is frigid enough, I was brought to Hollywood when very young, and lived all my life in sunshine and palms. When we got to the jumping off place near Mount Baker, I was unable to adjust myself to the cold. And it was bitterly cold, with worse to come.

“When we attempted to make the location camp on Mount Baker, our part had no sooner been bundled into cars when we met the studio trucks returning. Snowslides had blocked the roads. There was no hotel at the little settlement at Glacier. We were stumped.

“Fortunately Mr. and Mrs. Graham of Glacier made room for Mr. and Mrs. Reginald Owen, my companion, Mrs. Frances Earle, and me. Bill Wellman and Dorothy, his wife, pushed on by dog sled the next morning, and then a snowplow cleared the way for the rest of us. That was our introduction to the hardships to follow.

“A flimsy sound stage had been built near the summer lodge on top of Mount Baker, in case of blizzards. We drew a blizzard immediately, and tried to work on this stage. Wind whistled through it. My nostrils frosted shut, my feet seemed like cakes of ice. In that bitter cold, we could shoot for only a half hour at a time.

“We slept in the cabin annex to the hotel which had burned down, with little heat and all sorts of discomforts, but not a soul complained. Mrs. Clark Gable stuck it out valiantly, but she and I almost lost heart when one night the power plant broke down. Without lights or electric heat, we were ready to freeze to death for dear old 20th Century. I felt so sorry for the crew sent to repair the plant that I forgot my own discomfort and how we cheered them when they returned, successful, after battling three solid hours to reach the power plant through the snow. One of the boys passed out, and came very close to giving his life to save the rest of us from surely freezing.

“Clark and Jack Oakie and Director Wellman made life bearable with their unfailing good humor—though sometimes Jack also made life almost unbearable with his gags. But you have to forgive him—he is so contrite and innocent looking when he confesses a prank.

“We had plenty of frozen meat, but we were soon starved for fresh vegetables. I developed a tremendous hankering for a stick of celery—just one little piece of celery would have made me happy. For five days, we couldn’t even leave our cramped quarters, with the snow over the tops of windows and a howling blizzard raging. The partitions that divided our chicken-coop rooms where as thin as paper and afforded only visual privacy.

“Mrs. Earle had a birthday, and the chef stirred up a cake. We had speeches and celebrated grandly. Then Clark announced his birthday, and we celebrated again. I regretted that my own birthday, on January sixth, had arrived before our location trip. These little parties were a god-send to keep our minds off the privations.

“Making our way about camp required a guide to get us through the maze of deep cut snow paths. They seemed to lead everywhere. One night, we tried to find our way to the mess shack without our guide, Harvey, and became lost. Finally, we saw a light and got back to the cabins, but we were as frightened as we were frozen.

“There was real danger—avalanches for one thing—all about is, as we all knew, but the players and crew never became discouraged nor lost heart. Wellman kept things in an uproar. There was never a dull moment if he could help it.

“After Mrs. Earle sprained her ankle and another member if the party crushed a knee cap on the slippery paths, we went around with ski sticks to keep from falling. It was a thrilling experience, but I’d hate to repeat it!”

Their supplies had to brought in over sixty miles of mountain road from Bellingham, with the constant danger of snow slides blocking the way. All the males in the cast bristled with beards, which collected icicles in that brittle cold weather. Cabin roofs groaned under the weight of 30-foot drifts, windows glowed feebly from what light filtered through the snow.

The power plant episode described by Loretta nearly ended the location trip. A break occurred in the power line sometime after midnight, and the suffering community knew that all pine lines would soon freeze and burst. The work of the crew was truly heroic in repairing the damaged line which was found by frantically digging through drifts. No less real was the danger of food shortage when a Chinook (warm wind) melted drifts, flooded lower roads, washed out bridges, and no supplies could be brought in. Dog sleds finally got through with provisions in the nick of time.

The picture, all agree, is worth it. Call of the Wild, most famous of Jack London’s tales, is another triumph for youthful Darryl Zanuck.

Loretta Young, delight of directors and cameramen, is Cecil B. deMille’s The Crusaders, in which she now finds herself in other difficulties. But the hazards of such a picture will be nothing compared with the incredible hardships she suffered on location in white hell for you.