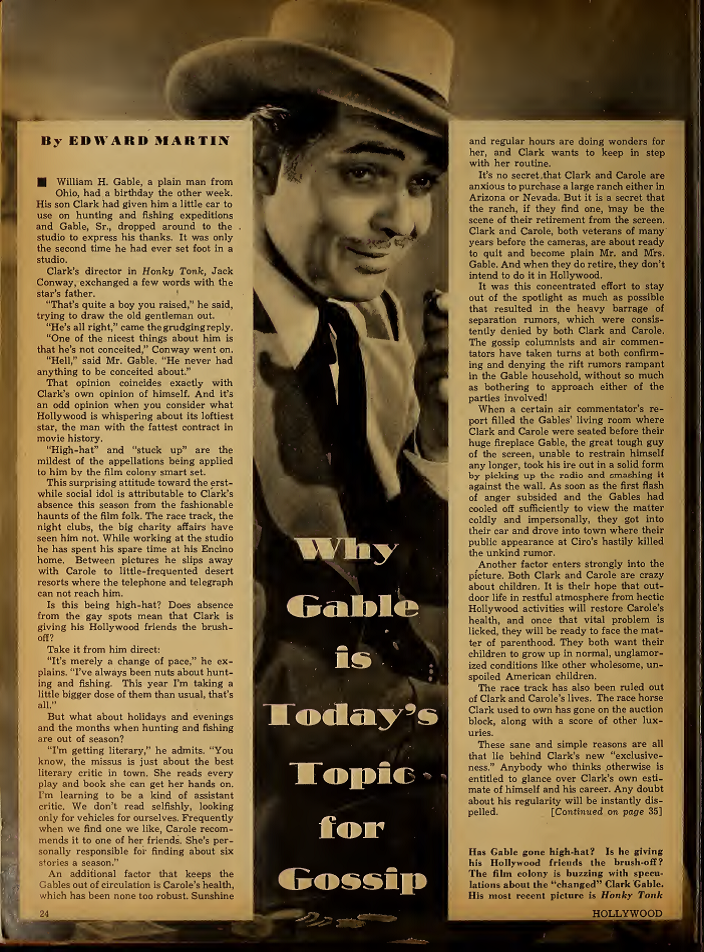

1941: Why Clark Gable is Today’s Topic for Gossip

By Edward Martin

Hollywood magazine, December 1941

William H. Gable, a plain man from Ohio, had a birthday the other week. His son Clark had given him a little car to use on hunting and fishing expeditions and Gable, Sr., dropped around to the studio to express his thanks. It was only the second time he had ever set foot in a studio.

Clark’s director in Honky Tonk, Jack Conway, exchanged a few words with the star’s father.

“That’s quite a boy you raised,” he said, trying to draw the old gentleman out.

“He’s all right,” came the grudging reply.

“One of the nicest things about him is that he’s not conceited,” Conway went on.

“Hell,” said Mr. Gable. “He never had anything to be conceited about.”

That opinion coincides exactly with Clark’s own opinion of himself. And it’s an odd opinion when you consider what Hollywood is whispering about its loftiest star, the man with the fattest contract in movie history.

“High-hat” and “stuck up” are the mildest of the appellations being applied to him by the film colony smart set.

This surprising attitude toward the erstwhile social idol is attributable to Clark’s absence this season from the fashionable haunts of the film folk. The race track, the night clubs, the big charity affairs have seen him not. While working at the studio he has spent his spare time at his Encino home. Between pictures he slips away with Carole to little-frequented desert resorts where the telephone and telegraph cannot reach him.

Is this being high-hat? Does absence from the gay spots mean that Clark is giving his Hollywood friends the brush-off?

Take it from him direct:

“It’s merely a change of pace,” he explains. “I’ve always been nuts about hunting and fishing. This year I’m taking a little bigger dose of them than usual, that’s all.”

But what about holidays and evenings and the months when hunting and fishing are out of season?

“I’m getting literary,” he admits. “You know, the missus is just about the best literary critic in town. She reads every play and book she can get her hands on. I’m learning to be a kind of assistant critic. We don’t read selfishly, looking only for vehicles for ourselves. Frequently when we find one we like, Carole recommends it to one of her friends. She’s personally responsible for finding about six stories a season.”

An additional factor that keeps the Gables out of circulation is Carole’s health, which has been none too robust. Sunshine and regular hours are doing wonders for her, and Clark wants to keep in step with her routine.

It’s no secret that Clark and Carole are anxious to purchase a large ranch either in Arizona or Nevada. But it is a secret that the ranch, if they find one, may be the scene of their retirement from the screen. Clark and Carole, both veterans of many years before the cameras, are about ready to quit and become plain Mr. and Mrs. Gable. And when they do retire, they don’t intend to do it in Hollywood.

It was this concentrated effort to stay out of the spotlight as much as possible that resulted in the heavy barrage of separation rumors, which were consistently denied by both Clark and Carole. The gossip columnists and air commentators have taken turns at both confirming and denying the rift rumors rampant in the Gable household, without so much as bothering to approach either of the parties involved!

When a certain air commentator’s report filled the Gables’ living room where Clark and Carole were seated before their huge fireplace Gable, the great tough guy of the screen, unable to restrain himself any longer, took his ire out in a solid form by picking up the radio and smashing it against the wall. As soon as the first flash of anger subsided and the Gables had cooled off sufficiently to view the matter coldly and impersonally, they got into their car and drove into town where their public appearance at Ciro’s hastily killed off the unkind rumor.

Another fact enters strongly into the picture. Both Clark and Carole are crazy about children. It is their hope that outdoor life in restful atmosphere from hectic Hollywood activities will restore Carole’s health, and once that vital problem is licked, they will be ready to face the matter of parenthood. They both want their children to grow up in normal, unglamorized conditions like other wholesome, unspoiled American children.

The race track has also been ruled out of Clark and Carole’s lives. The race horse Clark used to own has gone on the auction block, along with a score of other luxuries.

These sane and simple reasons are all that lie behind Clark’s new “exclusiveness.” Anybody who thinks otherwise is entitled to glance over Clark’s own estimate of himself and his career. Any doubt about his regularity will be instantly dispelled.

“I landed in Hollywood because I was pushed by cold weather and pulled by Number 7,” he recounts in his down-to-earth manner. “There’s been a lot of Hollywood baloney about lucky numbers. With me Number 7 isn’t a lucky number; it’s a GO signal, and I’m not kidding.

“When I was a kid in Cadiz it was my greatest ambition to get on the neighborhood sandlot baseball team. I was a big, ugly rawboned kid and didn’t look like material for the Cleveland Indians. But the fellows gave me a tryout. They didn’t own a mask so they let me be the catcher, expecting I would get my teeth knocked down my throat. They asked me what position I wanted to bat in and I said seventh, thinking I’d get beaned by the pitcher long before my turn at bat ever arrived. Well, old 7 gave me the Go signal. That day I hit three homers and got a regular job on the team.

“My first salaried job was in a rubber factory in Akron. I told a few fairy tales about my age and experience and went to work at $7 a day. When my Dad and I teamed up to work in the Oklahoma oil fields I made that same magic salary. In those days seven bucks looked magic to me. I still have a good healthy regard for seven bucks because in the intervening years I was so often without any bucks at all.

“On January 7th I joined up with a repertory company touring the West. I’ve been trying to be an actor ever since.

“But there was more cold and more Number 7’s between me and Hollywood. Our company went broke in Butte, Montana, on February 7th. Also, I personally went broke. Blizzards were in season and I had nothing but a cheesy little topcoat to ward off the wind.

“I went into a barroom to get something to eat off the free lunch table. In Butte it’s a hanging offense to enter a café without a silver dollar in your kick. Hunger makes me eloquent, I guess. Anyway, I jawboned the bartender out of a picnic meal. With a full stomach I felt adventurous again.

“I went down to the railroad station and cuddled up to the pot-bellied stove. On the bulletin board I noticed that Train Number 7, going West, was due.

“’That’s for me,’ I said, and went out to the freight yard. When Number 7 pulled out of Butte I and five other hoboes were in a nice coal refrigerator car. That train took me to Portland, a regular job in stock, and eventually to the Lost Mile performance in Los Angeles that landed me in pictures.”

Until he made Honky Tonk Clark had hardly an uncomfortable moment in California.

“A bad moment came at the end of my new picture. I’m supposed to be a tinhorn gambler, run out of every town in the West. One scene shows me running for a freight train. That touch had a little too much autobiography in it, too.”

Is this the guy Hollywood is calling high-hat? If so, Hollywood had better go wash its mouth out with soap.