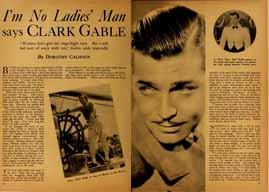

1935: I’m No Ladies Man, says Clark Gable

By Dorothy Calhoun

Motion Picture, October 1935

“Women don’t give me stage-fright now. But I still feel sort of wary with ‘em,” adds Gable reservedly

By the last exhibitor’s census, Clark Gable is Public Lover Number One of the Screen. And yet—out in Culver City—they have a hard time getting him into a dress suit in order to hold a girl against his starched shirt front while he looks down into her eyes and murmurs sweet nothings. It makes him—Clark explains—feel foolish. He isn’t—he insists—the Great Lover type. He doesn’t—he confesses—understand women, and he never will to the end of his days.

“Most boys learn about women from their mothers,” he says. “They unconsciously form their image of the girl they hope to marry someday by patterning their ideal after the one woman they know best. However, my mother died when I was only seven months old.”

The tough captain of a coolie ship in “China Seas” or the unshaven, unwashed castaway of “Mutiny on the Bounty”—these are the parts into which Clark really gets his teeth. “I know men like them,” he says. “I’ve been men like them!” he adds forcefully.

In the strangest life story of any screen star (which is Clark’s), every other chapter has been an episode, built upon raw realities—men pitting their strength against circumstances, men without comforts, or homes. Men without women. Between theatrical engagements, William Gable’s boy who ran away from home to be an actor could have been found in a brass foundry, laboring in the inferno of furnaces with men from the fields of Lithuania, or the coal-pits of Poland, sharing the slum-gullian of other brothers of the road in hobo jungles, or answering the welcome yell of “Come and Get It” with Oregon lumberjacks, out in the wilds.

“I’ve lived with lonely men most of my life,” Clark told me, pushing back one straggling black lock (his unruly hair, strong and straight is the despair of make-up men but it would be a brave director who would suggest to Clark Gable that he get a permanent). He continued speaking.

“Most fellows of my age were taking girls to the Hopedale high school dances when I was mucking in the oil fields,” he remarked. “Those years when boys are being educated in the ways of the world—and especially the ways of women—I was traveling with some one-horse road show, learning a new play every week, helping with the scenery, and acting everything from a butler in “Romeo”, or else I was stranded in some God-forsaken place where I had to get whatever work there was to be had. No time for calling on a girl in the evening with a box of chocolates. No dances! No girls! I skipped that part of my life. Why, don’t you know, when I began to get into the better theatrical companies, and Broadway shows, I look lessons in the things most men of my age had known for years!

“I learned how to come into a drawing room gracefully, how to hold a tea cup, how to bow and how to sit and talk the patter of polite society. In other words I had to learn my manners. Lumberjacks aren’t in the habit of taking afternoon tea. Telegraph lineman are more at home in a one-arm lunchroom than at a formal dinner party. Hoboes aren’t finicky about forks.

“Naturally, after such a life as mine, I’m more at home with men than I am with women. But I think most men are. They talk the same language. When a man says anything, no matter whether he’s a millionaire or a truck-driver, he means just one thing. But I’ve learned that when a woman makes a remark, she may mean a dozen things! I can pretty nearly figure out how any man I’ve ever met will act under certain circumstances, but I can never tell what a woman will do!

“I’ve met more women in the five years since I’ve been in Hollywood, than I ever knew in the other twenty-nine, and I’ve learned something of course. I’ve learned that all women have a quality of the mother in them. This makes them heavenly kind in trying to help a fellow along. I’d never be where I am today, if it hadn’t been for six women who were willing to take time from successful lives to encourage and comfort and teach a struggling young actor. I’ve learned how to talk to women, too, and say—more or less—what I’m expected to say. I believe they call it ‘making conversation.’ Men alone don’t feel the necessity of talking unless they have something real to say. I’ve worked for days in a factory, shoulder to shoulder with other fellows, without exchanging a word. Evenings in the mountains—where I go between pictures for shooting and camping—I can spend around a fire with a guide and a couple of other natives—whittling, cleaning guns, and speaking only now and then with long silences between.

“Women don’t give me stage fright as much as they did once. Women in general, I mean, but I still feel self-conscious and sort of wary with ‘em. I guess I’m just not a ladies man!”

Clark Gable is the one screen star who can talk to a woman as though she were a man, an intimate friend at the studio once told me. After that, I watched him—and eavesdropped—while he conversed with a lady-interviewer, a script girl, a beautiful screen star, a publicity woman. He told the interviewer—who was trying to get him to talk about “Marriage”—the correct way to play a trout. He and the script girl got into a discussion about skeet shooting at which they both practiced every lunch hour. The star, noted for her silken boudoir appeal, was regaled with a dissertation on the cleaning of a carburetor—with pencil illustrations on the back of one of her new photographs! To the publicity woman, who had been sent to get his vote on the Ten Most Attractive Women Stars of the Screen fir a newspaper syndicate, he told a long anecdote about a duck-shooting trip from which he had just returned.

“I tell you frankly,” Clark grinned, “I haven’t the hang of this interview business yet. I still feel sort of silly talking about my feelings, and giving my ideas on every subject, but I know it’s part of the business—the strangest business in the world for a man to be in. Nothing will make me a social light, I guess. I’d rather sit around a garage discussing motors with the mechanics than get into a white tie and tails and spend an evening making conversation as the dinner partner of some beautiful woman star!

“I go to a few parties, to the polo games, the fights and to the races at Santa Anita. But my idea of a grand time is—now and always—to pile camping equipment and guns into my car and start out.”

On the evening of the first Mayfair dance of the past season—the occasion for which all the crown jewels of Hollywood are taken out of safe deposit boxes and the night when every star tries to out-dazzle every other star—a publicity man, driving down from San Francisco, overtook the sturdy figure of a wayfarer, tramping toward the Mojave Desert, pack on back, gun slung over his shoulder. Fifty miles away from where the Hollywood stars were dancing at the movie colony’s most festive occasion, with news cameras clicking, Clark Gable was happily walking the dusty roads, beneath bright desert stars.

Last year, Clark allowed himself to be talked into making a personal appearance tour (he wakes up even now in the middle of the night in a cold sweat dreaming of that tour, he tells me). He has been more woman-shy than ever since his return. When, recently, he went down to Texas to see his step-daughter, Georgiana, married, somebody saw him getting into the plane to leave from Hollywood. As he sailed peacefully through the blue of the Arizona sky, automobiles began to roar up to the airport that he would soon reach, while their occupants, mostly feminine, surged out on the field, applying lipstick as they ran. With the buildings of the Texas city in sight beneath them, the pilot told the unsuspecting Clark the news that he had just received by radio. “There’s a crowd of ten thousand women waiting for us on the field,” he said. “Get the dimple working, bo!”

To Clark Gable’s horrified eyes the land, which they were approaching rapidly, swarmed with feminine hats. A million (more or less) upturned faces seemed to watch the plane’s descent hungrily.

“Listen,” Clark told the pilot desperately, “Have a heart! Couldn’t we land somewhere else? I can’t get out into that mob! How would I act? What would I say? What could I do?”

A low roar, reminiscent of that of hungry lions at a zoo, came to their ears above the hum of the motors. The pilot looked at the movie star. A few moments before, he had been envying him. Now, from his heart, he pitied him.

Clark Gable had faced cornered mountain lions in Wyoming wilds. He once pursued a bear to his den. Once he helped cap an oil well that was on fire. But he knew enough by sad experience to pale and tremble at the sight of a mob of women movie fans with their scissors drawn!

“Okay,” said the pilot, pushing his stick forward and zooming up into the skies, “We land at Miles Field, Mister.”

“They were grand to want to meet me,” Clark said when I brought up the subject. “Of course, I’m not the man they wanted to see, not me—Clark Gable from a small town in Ohio, the fellow who hasn’t any pretty parlor talk and would rather toss a flapjack over a sagebrush fire than eat something under glass at a Hollywood night club. They expect to see the Gable they know on the screen—whoever he is. And I’m always afraid of disappointing them. I never have learned what to say when women flatter me because of my acting.”

“But praise is one of the biggest rewards for being a movie hero,” I protested. “You don’t mean to tell me that you don’t want it?

“Of course not,” said Clark, “What man would?”

He may be Public Lover Number One to the fans but he doesn’t belong in Hollywood. The temptations of the most publicized town in the world are not for him. Fame? He doesn’t know what to do with it. Money? He has no need or desire for most of the luxuries that his earnings could buy for him. Good times? The Hollywood definition of pleasure isn’t in Clark’s dictionary. Romance? He is happily married and doesn’t care who knows it. Wherever he goes in society, Ria Gable, his wife, charming and suave, is at his side.

With the beautiful and famous women stars of the films begging for him as a screen lover, his name has never been connected with theirs in this most gossipy of all towns.

“It’s a job,” he says briefly. “I like it better than any other job I’ve ever had. But it won’t break my heart when it’s over. There’s always something interesting to do in this world. Hollywood won’t be a habit hard to break for me. I never have dug in here particularly. It’s only this last year that I’ve had a house. Before that, I always felt so temporary that my wife and I have lived in apartments so that—when the movies were through with me—we could pick up and go. I don’t know so many people here. Most of my intimate friends are trappers and guides in the Arizona hills where I go between pictures. I haven’t even built a bar into my house. Nor invested in a swimming pool!

“I haven’t been in the big salary class very long, and so I won’t miss it so much when it stops coming. A man who’s chivvied huge logs down flumes for his living has a different notion of money from that of most actors. To me the money you earn by the sweat of your brow is more real somehow than Hollywood salaries. I’ve had to gauge my spending by that sort of earning so long that I haven’t acquired expensive tastes. And, I guess, now it’s too late to begin. I don’t suppose that I’d want to live again the way I’ve been forced to live at times, but my ideas of a good income are ridiculously far below Hollywood’s.

“And, among the things I won’t miss when I leave Hollywood (as all screen stars do sooner or later) is the necessity of living up to the public’s idea of how a movie actor should look and act—and talk!”

That’s the way Clark put it. And that was just what he meant!