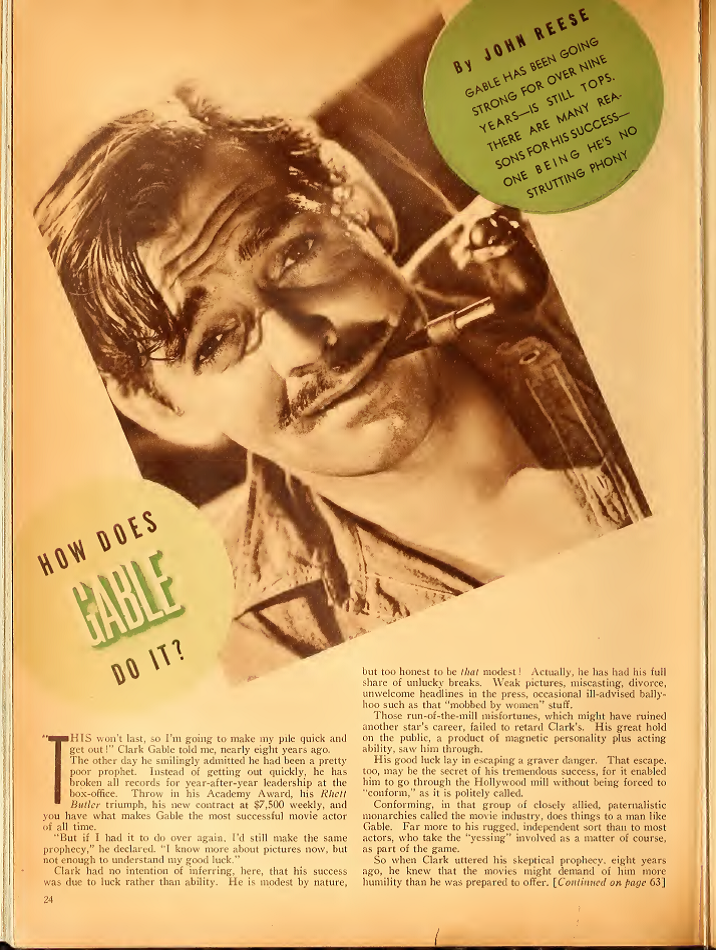

1940: How Does Gable Do It?

By John Reese

Motion Picture, July 1940

Gable has been going strong for over nine years—and is still tops. There are many reasons for his success—one being he’s no strutting phony.

“This won’t last, so I’m going to make my pile quick and get out!” Clark Gable told me, nearly eight years ago.

The other day he smilingly admitted he had been a pretty poor prophet. Instead of getting out quickly, he has broken all records for year-after-year leadership at the box office. Throw in his Academy Award, his Rhett Butler triumph, his new contract at $7,500 weekly, and you have what makes Gable the most successful movie actor of all time.

“But if I had it to do over again, I’d still make the same prophecy,” he declared, “I know more about pictures now, but not enough to understand my good luck.”

Clark had no intention of inferring here, that his success was due to luck rather than ability. He is modest by nature, but too honest to be that modest! Actually, he has had his full share of unlucky breaks. Weak pictures, miscasting, divorce, unwelcome headlines in the press, occasional ill-advised ballyhoo such as that “mobbed by women” stuff.

Those run-of-the-mill misfortunes, which might have ruined another star’s career, failed to retard Clark’s. His great hold on the public, a product of magnetic personality plus acting ability, saw him through.

His good luck lay in escaping a graver danger. That escape, too, may be the secret of his tremendous success, for it enabled him to go through the Hollywood mill without being forced to “conform,” as it is politely called.

Conforming, in that group of closely allied, paternalistic monarchies called the movie industry, does things to a man like Gable. Far more to his rugged, independent sort that to most actors, who take the “yessing” involved as a matter of course, as part of the game.

So when Clark uttered his skeptical prophecy, eight years ago, he knew that the movies might demand of him more humility than he was prepared to offer. More than he dared offer, in fact, for as this friend, Lionel Barrymore, pointed out, Clark’s unique screen appeal was a fearless virility, which no cowed actor could stimulate by phony strutting.

“These big salary checks they hand out every Wednesday aren’t going to make my kiss anyone’s feet,” he announced, “I can make a living anywhere, and I’ll soon have a stake big enough to let me travel, which is what I want to do most of all, anyway.”

Having made this decision and boldly declared it, so all listening stool-pigeons and hidden microphones might hear, he stuck to it. He has kowtowed to none, kissed no feet. And in all these passing years, no movie monarch has cried, “I don’t care if Gable is a gold mine—off with his head!”

In fact, few controversial issues with movie royalty ever confronted Clark, either in the various studios where he worked, or in the dangerous atmosphere of Hollywood social intrigue. When those rare occasions did arise the star, friendly, reasonable but determined, never lost “face.”

His one important rebellion, instead of proving costly, led to his luckiest break. That was some years ago, when he realized that in playing meaningless roles opposite certain female stars, his own box office strength was being sapped in a futile endeavor to increase theirs. He called a halt.

As punishment he was “loaned out” to Columbia to do a “little” picture. The picture was It Happened One Night, and Clark got the Academy Award for his work in it, besides tremendous added prestige and popularity.

While his uncompromising refusal to “conform” the Hollywood way has been a mighty factor in his success and durability, Clark’s whole temperament and philosophy suit him for his job. In his nature are none of those jangling complexes that prey on so many actors.

“Nerves? Some people seem to have ‘em, but what good are they?” he quipped one day. He wouldn’t know, for his never trouble him.

He has too much aggressive courage to worry, too much healthy self-confidence to feel the mean pangs of professional jealousy. And he is a living contradiction to the old-fashioned belief that a fine actor must be high-strung, fragile in sensibility, full of “temperament.” Or that good trouper “on” must be a four-ring circus of exhibitionism “off.”

With all his sensible qualities, Clark has quick intelligence, a keen sense of logic and reason, excellent judgment. You can slip anything over on him. But his humor is double-acting; if the joke is on him, it’s just as funny to him as though it were on someone else.

The humanness and unspoiled “realness” is revealed increasingly, the longer and better you know him. It is not too much to say that his earthiness, in the Hollywood glamour whirl, remains as unaffected as was Lincoln’s in the White House.

Many a time, his huge and lusty enjoyment of simple things has annoyed the film-town show-offs, just as Lincoln’s simple tastes annoyed the pretenders at Washington.

“You’re the oddest chap, Clark!” one noted actor exclaimed in my hearing as he watched Clark blissfully peeling and eating bananas, and gulping down milk directly from the quart bottle.

“How come?” the star asked.

“Instead of that stuff, you could lunch on champagne and caviar…”

“Sure, if I liked ‘em,” replied Gable. Then he added with a chuckle, “Maybe it’s wrong to eat what I like instead of what’s expensive, but I can’t help it—I’m so nuts about bananas!”

His zest for farm life is another enigma to many, including even some stars who pose as “gentlemen farmers.”

“What’s the good of having a farm if you don’t work on it?” Clark asks them. “I’ll admit I didn’t like farm work when I was a kid, because I had to do it then. Now I get fun out of it. The exercise, change and quiet seem to recharge my batteries. I come back to the studio, after a spell out at my place, with a lot more pep.”

That may be true, but I have never seen Clark when he seemed to nee battery recharging, or more abundant energy. His vitality and interest in life are revealed; even during those deadly dull waiting periods between scenes, on some movie sets.

Every time I see Clark on a set, except when he is working or in rehearsal, he’s in the middle of a lively group—most often a group of husky studio electricians, “grips,” and so on. He is not a famous star among them, but by his unaffected geniality and enjoyment, becomes literally one of them. His hand smacks resoundingly on the shoulder of a burly stage carpenter. His guffaw, at someone else’s quip, rings out loud and unrestrained. He gets out of his canvas chair with a spring that is almost feline; sits down again to flow back into easy, tensionless relaxation.

Another famous male star I know spends the between-scenes period in jittery, hectic activity, keeping up his eternal off-stage act of pretended enjoyment, good-fellowship, pep. It rings as false as Gable’s rings true, and one can see that it has worn the actor himself, down to raw nerves.

A third male star I have often watched is dull, taciturn, glum. Between scenes, he mutters something about “taking a nap” or “studying dialogue,” and disappears into his portable dressing room. There he quaffs a quick one.

While both of the other actors are famous, neither is as successful as Gable. If other things were equal, Clark would win superiority by his between-scenes manner.

I am told by directors that Gable’s acting style give him another natural advantage over rivals, in that it is so easy, natural, and unaffected. The studious underplaying of Spencer Tracy, the highly technical work of Paul Muni both take more from their exponents. Yet Gable’s work, at its bets, is preferred by many in Hollywood to that of either of his fellow Academy Award winners.

If he can accomplish at least as much as they do, with less drain on the storehouse of his energy, that is one more “edge” Clark holds over his competitors. Just another factor in his unbelievable-but-true record of eight years: in the first ten, three of them as leader, two are runner-up.

Gable calls himself a “ham,” says his acting isn’t art, and admires the Tracy style, but feels it is not for him.

“The only way I can be convincing is to do my acting in my own funny way,” he remarked on one occasion.

Once I sat in on a casting conference at a certain studio. They wanted a skilled “name” actor to play the part of a typical, successful movie star. Freddie March, Leslie Howard and several others were mentioned favorably. The someone said, “I think we might even get Gable, if you want to lay out the dough for him.”

“Not at all the type!” cried the producer.

That was one occasion when I could “yes” a producer and mean it. Gable, one of the greatest movie actors of all time, certainly isn’t the type I’d choose to play a typical movie actor.

The fact that he isn’t the type has contributed to Gable’s enduring greatness. Too many screen heroes fall into the typical Hollywood mould, or are remade to fit it.