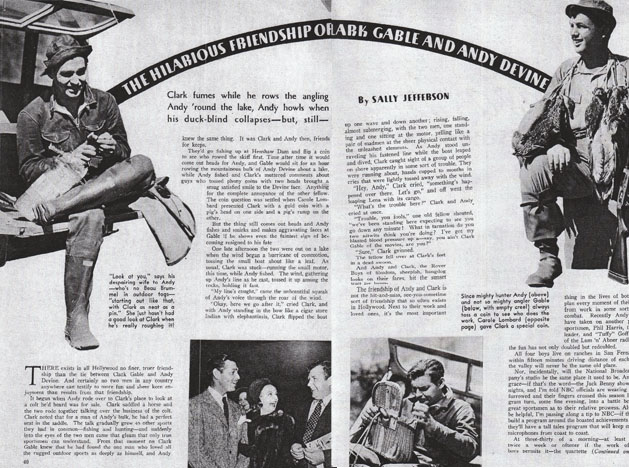

1939: The Hilarious Friendship of Clark Gable and Andy Devine

By Sally Jefferson

Movie Mirror, February 1939

Clark fumes while he rows the angling Andy ‘round the lake, and Andy howls when his duck blind collapses—but, still—

There exists in all Hollywood no finer, truer friendship than the tie between Clark Gable and Andy Devine. And certainly no two men in any country anywhere can testify to more fun and sheer keen enjoyment than results from that friendship.

It began when Andy rode over to Clark’s place to look at a colt he’d heard was for sale. Clark saddled a horse and the two rode together talking over business of the colt. Clark noted that for a man of Andy’s bulk, he had a perfect seat in the saddle. The talk gradually grew to other sports they had in common—fishing and hunting—and suddenly into the eyes of the two men came that gleam that only true sportsmen can understand. From that moment on Clark Gable knew that he had found the one man who loved all the rugged outdoor sports as deeply as himself, and Andy knew the same thing. It was Clark and Andy then, friends for keeps.

They’d go fishing at Henshaw Dam and flip a coin to see who rowed the skiff first. Time after time it would come out heads for Andy, and Gable would sit for an hour rowing the mountainous bulk of Andy Devine about a lake, while Andy fished and Clark’s muttered comments about guys who tossed phony coins with two heads brought a satisfied smile to the Devine face. Anything for the complete annoyance of the other fellow. The coin question was settled when Carole Lombard presented Clark with a gold coin with a pig’s head on one side and a pig’s rump on the other.

But the thing that still comes out heads and Andy fishes and smirks and makes aggravating faces at Gable if he shows even the faintest sign of becoming resigned to his fate.

One late afternoon the two were out on a lake when the wind began a hurricane of commotion, tossing the small boat about like a leaf. As usual, Clark was stuck—running the small motor, this time, while Andy fished. The wind, gathering up Andy’s line as he cast, tossed it up among the rocks, holding it fast.

“My line’s caught,” came the unbeautiful squeak of Andy’s voice through the roar of the wind.

“Okay, here we go after it,” cried Clark, and with Andy standing in the bow like a cigar store Indian with elephantiasis, Clark flipped the boat up one wave and down another; rising, falling, almost submerging, with the two men, one standing and one sitting at the motor, yelling like a pair of madmen at the sheer physical contact with the unleashed elements. As Andy stood unraveling his fastened line while the boat leaped and dived, Clark caught sight of a group of people on shore apparently in some kind of trouble. They were running about, hands cupped to mouths in cries that were lightly tossed away with the wind.

“Hey, Andy,” Clark cried, “something’s happened over there. Let’s go,” and off went the leaping Lena with its cargo.

“What’s the trouble here?” Clark and Andy cried at once.

“Trouble, you fools,” one old fellow shouted, “we’ve been standing here expecting to see you go down any minute! What in tarnation do you two nitwits think you’re doing? I’ve got my blasted blood pressure up a—say, you ain’t Clark Gable of the movies, are you?”

“Sure,” Clark grinned.

The fellow fell over at Clark’s feet in a dead swoon.

And Andy and Clark, the Rover Boys of filmdom, sheepish, hangdog looks on their faces, hit the sunset trail for home.

The friendship of Andy and Clark is not the hit-and-miss, see-you-sometime sort of friendship that so often exists in Hollywood. Next to their work and loved ones, it’s the most important thing in the lives of both men, who plan every moment of their time away from work in some sort of friendly combat. Recently Andy and Gable have taken on another pair of true sportsmen, Phil Harris, the orchestra leader, and “Tuffy” Goff, the Abner of the Lum ‘n’ Abner radio show, and the fun has not only doubled but redoubled.

All four boys live on ranches in the San Fernando Valley within fifteen minutes driving distance of each other, and the valley will never be the same old place.

Nor, incidentally, will the National Broadcasting Company’s studio be the same place it used to be. Andy and Phil grace—if that’s the word—the Jack Benny show on Sunday nights, and I’m told NBC officials are wearing their brows furrowed and their fingers crossed this season lest the program turn, some fine evening, into a battle between these great sportsmen as to their relative prowess. Always one t be helpful, I’m passing along a tip to NBC—if they will just build a program around the boasted achievements of this pair, they’ll have a tall tales program that will keep ears glued to microphones from coast to coast.

At three-thirty of a morning—at least once, and twice a week or oftener if the work of the four boys permits it—the quartette will meet at Clark’s or Andy’s and they’re off for their duck blinds in Andy’s trailer. Lies, the likes of which no professional liar at his best has yet topped, will then solemnly occupy their time on the way to the blinds. Andy will swear the bass he lost under a rock yesterday was not only bigger than Joe Penner, but looked like him. Phil will sneer and tell about the fish he and Tuffy threw back into the lake just before it threw them in. Gable will vow that he sneaked away yesterday for a bit of fishing (although the other three know darned well he never left the “Idiot’s Delight” set) and brought home a fish that took two Chinese cooks and Jack Benny’s Rochester to prepare.

And then, each well satisfied that he has outdone the others, they’ll arrive at their duck blinds for their sport. Gable and Andy teamed together in one blind (a sort of sunken barrel in the earth) until the awful day when, due to Andy’s bulk, they got stuck and it took Tuffy, Phil and a farmer named Eb—who talked just like Tuffy on the radio—to pry them out. It was then the boys built for Andy a blind eight feet wide. The talk of its furnishings among Gable, Tuffy and Phil—whether the color scheme should be apple green or a lavenderish orchid, the draperies of two-toned beige with openwork fringe—set Andy wild, and the boys loved it. Because of its size they call it “The Queen Mary Blind.” “I’m going over to the Queen Mary,” Gable will call.

The lies and kidding over, the boys settle down for a long, dreary wait that only a real sports’ lover could endure. And then out of the daybreak will come the whirr of wings, and the bark of guns, and the howls of insults from Phil and Tuffy’s blind across the marsh if Gable and Andy miss. And back will go the insults if Phil and Tuffy miss…and then the hours of waiting again.

Andy, who surprises Clark with the ease which he handles his bulk in riding, hiking or running, never seeming to be tired or winded, occasionally comes to a cropper that positively rolls Gable on the ground.

There was the day Andy, from his own blind, walked over to Gable’s blind to talk about a gun, and without noticing sank slowly into the mire up to his ankles. As he turned to leave, he fell headlong into the mud and lay there, face down, unable to move an inch.

“”I’d have given anything I have,” Andy told me, “if it hasn’t happened before Gab (his nickname for Gable) for now I’ll never live it down. All the lies Gab told about having to rent a derrick to get me up were false. It wasn’t a derrick at all. It was only a plow horse.”

One day Andy and Clark, clad in the rubber waders that come up around their chests, their hunting hats pulled into peaks in the front, were parading in a duck marsh. “I wish,” Andy told me, “you could have seen glamour boy Gab in that rig. Anyway, we were walking along when suddenly a man and a boy came along and stopped dead at the sight of us. ‘Gee look, Pop,’ the boy cried, ‘there goes a couple of the biggest penguins I ever saw.’”

The paying off of the fishing bets and the nightly game of pitch before the campfire are the two most feverish activities of the day. After long patient hours—maybe twelve at a stretch—under a hot sun or in stormy gales on a lake as they indulge in the game they love, the nightly paying off becomes the panic of the day. The bets are one dollar for the first fish caught, one for the biggest and one for the greatest number caught by one person that day. You would think, I swear it, from the struggle that goes on to outdo the one another, the arguing and shouts across the campfire over who won what, that life or death depends on these bets. The arguments over and the bets paid off to the accompaniment of squawks and groans, the game of pitch begins, to end with the dawn’s warning that another day of beloved fishing is about to begin.

When Clark, because of work, can’t join the rest, Andy, with Phil or Tuffy, will parade grandly up and down before Gable’s house, waving guns or fishing tackle, and talking loudly of the wonderful time in store. And maybe the very next day it will be Gable’s turn gleefully to taunt Andy or Tuffy.

But once, just once, let the boys get wind of a country auction of guns or saddles or other stable equipment and nothing can prevent a gathering of the clan. There they’ll sit—Andy, Clark, Tuffy and Phil—on a rail fence watching with avid interest the sale of a second-hand horse blanket. A famous orchestra leader, associated with tails and white ties and soft music and lights and night life; a young man thirty years old conceded to be one of radio’s greatest impersonators of country characters; a monstrous comedian of the movies and Clark Gable, the greatest hero on the screen today.

“All of us were small town or country boys,” Phil told me, “and we just naturally never got over it. We were born and raised in the sticks, and it’s right down inside us and that’s the way we’ll always be, I guess.”

And there sit this odd assortment on a countryside rail fence listening eagerly to the sale of a badly used saddle. And maybe buying it.

“I wonder,” Clark will sometimes murmur when fishing on a cool, clear lake, “what those actors are doing under the hot lights on stage three today. Hot dog!”

The sudden acquiring of bird dogs by Andy and Tuffy left Clark in a blue funk. “You said I could have your other dog,” Clark keeps reminding Tuffy, who swears he did no such thing. In fact the day Andy and Tuffy left to pick up their dogs, Gable was deep in a scene with Norma Shearer for “Idiot’s Delight.” But Andy hasn’t forgotten his friend. He hired an extra to parade up and down before Gable’s dressing room door between scenes and act like a bird dog.

In order to hunt in peace the four chipped in and bought property together high in the Northridge section. They promptly named it “The Hardrock Land Company” and voted Tuffy the president. One would have to see Tuffy, a mere five feet two or three in height, among the other three six-footers, to appreciate the hilariousness of Tuffy’s job as the president who runs and bosses the affairs of the “Hardrock Land Company” and the Hardrock boys. And no monkey business.

It’s poor Andy who comes in for lectures on neatness and tidiness by Mrs. Devine who tried hard, heaven knows. “Look at you,” she’ll say, “starting out like that with Clark neat as a pin.” So Clark and Andy have worked out a scheme. Andy wears what he calls his “going away” clothes to please Mrs. Devine, but in another bag he sneaks the things he really loves to fish in, so Clark will always stop a safe distance away from the house and say, “All right, Andy, it’s safe to change your ‘going away’ clothes now.”

A pair of old moccasins with leather soles are the love of Andy’s life for fishing and no matter where Mrs. Devine hides these beauties, Andy manages to unearth them.

“They’re demoralizing, Andy,” Mrs. Devine was scolding one morning when suddenly Clark stood in the doorway, and as one their eyes riveted on his feet. He wore a pair of moccasins identical with Andy’s.

“Gee,” Clark said, “I had to hunt all over town to get a pair like yours, Andy.”

Sometimes Carole Lombard, Clark and the Devines will hie off to a picnic and take in a fair as they did at Pomona, or go to a special preview of Clark’s or Andy’s or Carole’s pictures. Clark is always right there to help Mrs. Devine pull a surprise party on Andy as he did last week by keeping him out on a lake all day, or maybe the two boys will sit of an evening just listening and cleaning their guns, while Carole and Mrs. Devine discuss the advisability of new dining room curtains.

“You’d think,” Andy said, “all the adulation and flattery and all the long years of it might in just some little way affect Clark. It hasn’t. I’m closer to him I guess than any fellow in town and I’ve never known a plainer, more honest, down-to-earth guy. Sometimes when we stop in some little eating joint along the way a crowd of people will gather to see Clark and it never bothers or fazes him. He has a ‘How are you’ and ‘Hello’ for everyone, and that’s the end of it. It just doesn’t penetrate to his vanity. Sometimes passing motorists recognize him and darned near wreck their cars looking back, so Phil and Tuffy and I take the bows for him, standing up and bowing all over the place.

“You’d think he’d have the most expensive fishing and hunting equipment in the world, wouldn’t you? Clark’s is just the same as the other boys’, just a plain old kit with every necessity, but no silver plated geegaws. Not for Gab!”

Yes, it’s a grand friendship of two men who know how to have a good time while the rest of Hollywood is feverishly trying to find the way to happiness. And they’re probably the two greatest friends in all moviedom, hilarious for their contrasts and pranks, but true down to the farmer-hearts of both of them.

One Comment

Wayne Hartlich

I’m pretty sure that both Clark & Andy got some of their dogs from a kennel in Wisconsin owned by my dad’s cousin. I believe they also would go to Canada & other places duck hunting with “Kurt” & his champion field dogs.