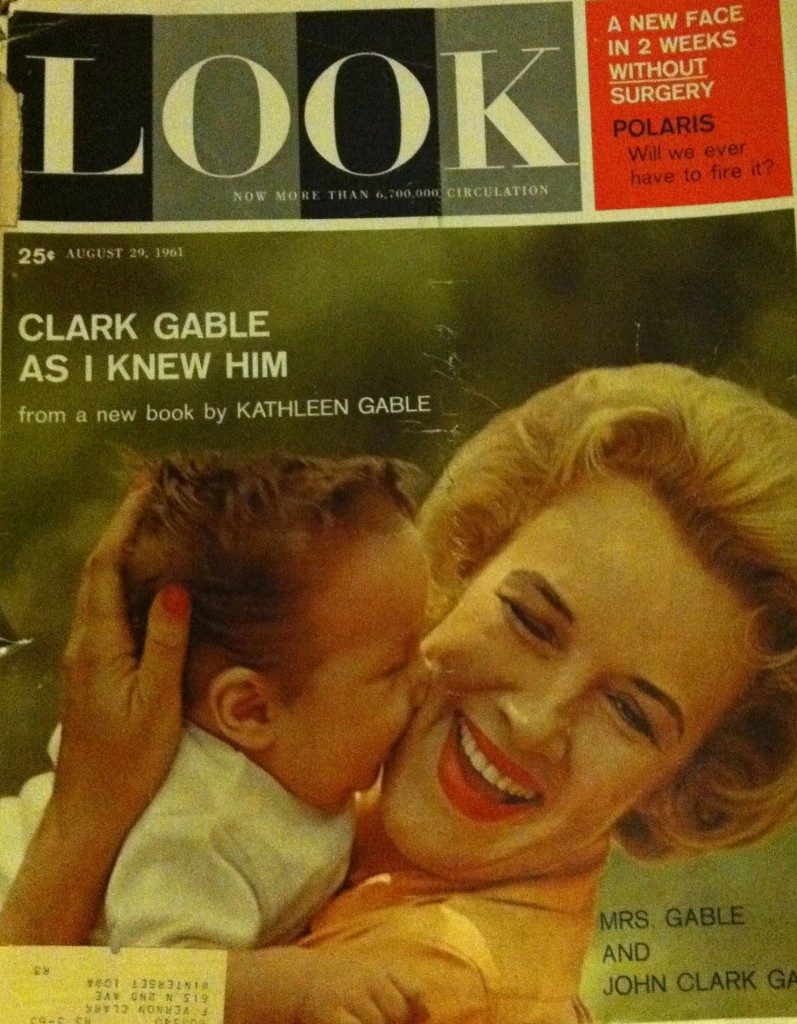

1961: Clark Gable as I Knew Him

By Kathleen Gable

By Kathleen Gable

Look, August 29, 1961

(Excerpts from her book, Clark Gable: A Personal Portrait)

Clark Gable’s widow tells about their life together and the son he never saw

One night shortly after my husband’s death, filled with an overpowering sense of sorrow, I went into his study and knelt beside his favorite chair. I prayed for him, and I wept. Then I felt the soft hands of my young son on my shoulder.

“Mother,” Bunker said, “crying isn’t going to bring Pa back, but if it helps you, go ahead. In the meantime, you’re sort of ruining Pa’s good leather chair with all that salt.”

There will be very little salt on these pages.

Clark Gable and I were married for only five years and four months. But we were ready for them, and we used them wisely. What we had in that time together was so beautiful that at first I —words to describe it. Then I realized it was really very simple—we had love.

Looking back over that period, I wonder if there are many people who, even in 25 or 50 years of marriage, find the happiness that Clark and I had. He loved me, and I loved him. Once that was established, we made no bones about it. We didn’t play silly games, like trying to make each other jealous. We were too busy trying to make each other happy. One way we did this was to listen to each other. We enjoyed talking together. There was a general communication between us. I think there are too many couples who talk AT each other.

I turned down the first invitation I received to meet Clark Gable. This was in 1942, shortly after I arrived in Hollywood. I had a stock contract at MGM, where he was the reigning star, and one day I received a call from Benny Thau, an MGM executive.

“We’re giving a little going-away party tomorrow night for Clark Gable—he’s leaving for overseas service,” Mr. Thau said. “I’d like to invite you as Clark’s dinner partner.”

This sounded like a command performance. I told Mr. Thau I was terribly sorry, but I had another engagement I couldn’t break.

Shortly after I hung up, another executive telephoned. He repeated the invitation. Politely, I declined again. Then came a third call. Mr. Thau was back. He thought perhaps I had changed my mind. I hadn’t. Apparently, they just couldn’t believe an unknown young contract player named Kathleen Gretchen Williams would turn down a chance for a date with Clark Gable. “I’m sorry,” I repeated firmly, “I’ll just have to wait and meet him some other time.”

That time came about six months later. There were no intermediaries on the phone this time. “Miss Williams, this is Clark Gable. I’m home on leave,” he said. “I wonder if you’d have dinner with me tomorrow night.”

“I’m afraid I’m busy,” I answered.

“What day aren’t you busy?” he inquired, sounding just a little amused. I informed him that Wednesday was open, and he promptly replied that Wednesday was fine with him.

“How would you like to have dinner at my house?” Clark asked and added, “The ranch is really beautiful at this time of the year.” I said that sounded lovely. “I’ll call for you at 7:30,” promised Captain Gable.

He rang my bell at exactly 7:30. (I don’t think he was ever late in his life.)

We headed towards Clark’s Encino ranch. The big electric gate which guards the entrance opened for only a few of his closest friends in 23 years. Unlike many of his colleagues, he never invited the press into his house. His innate shyness, his reserve and natural dignity precluded any such wide-open door policy.

I’ll never forget my reaction as we drove the quarter mile of winding road to the house. It was not just what I saw, it was also what I sensed—an air of peacefulness. Solid hedges of oleander trees bordered the drive. Clark cherished the half-mile stretch of Etoile de Hollande climbing roses that he and Carole Lombard had planted during the early days of their marriage. So do I.

I should mention that we weren’t entirely alone on our first date. Clark had a Siamese cat named Simon, a dachshund named Commission and a beautiful hunting dog named Bobby. The whole troupe escorted us to the dining room. A few moments later, Jessie, the cook, came through the swinging door, bearing a large Spode platter with a tremendous roast of beef, surrounded by Yorkshire pudding and gravy. That platter was balanced on one hand, held high over her head.

Just as she approached the table, the cook tripped over the braided rug. She went down with a great crash. Yorkshire pudding plopped onto the table. Hot gravy splattered over everything. And that great big beautiful roast landed on the floor along with Jessie. But not for long.

Bobby, a hunter to the core, made the fastest retrieve in history. With jaws clamped firmly around the meat, the dog tore out of the room before anyone could recover. Meanwhile, the dachshund was attacking slices of beef, and the cat quickly grabbed a big hunk of Yorkshire pudding.

My dress was soaked through with gravy. Clark looked over. “Well,” he said, flashing me that grin, “the first date you have with me, you end up in the gravy. I imagine I’ve made quite an impression on you.”

We ended up our first date at the kitchen table, laughing and talking over bacon and eggs.

Later, rumors had it that I fell madly in love with Clark at first sight and desperately wanted to marry him, but that he was executing a characteristic Gable defense maneuver. When we stopped seeing each other, about a year after we met, it was duly reported that I had overplayed my hand and had frightened Gable off.

The rumors didn’t particularly upset me. The reason was very simple—Clark and I were not deeply in love that first year. There was no great, great romance, just gaiety and amusing times together. When we stopped seeing each other, it was without any difficult scenes of parting. Clark phoned me to say good-by before he left for New York. As we were winding up our pleasant conversation, Clark remarked lightly, “Please, Kathleen, don’t get married again.” I replied, “May I say the same to you, my dear—and bon voyage.”

Clark didn’t write or telephone for the next ten years. Nor did I make any attempt to contact him.

I think the tragedy of losing Carole Lombard, whom he loved so devotedly, had left Clark with deep restlessness. He needed time to repair his own emotional bridges—time to travel, to be free of responsibilities.

I, too, needed time to develop and grow. I was 25 when I first met Clark, and I needed time to get to know myself. I don’t think either of us was ready for a mature, meaningful marriage at that point in our lives. But Clark disagreed.

Often, after we were married, during those long, happy evenings we spent relaxing, he’d turn to me and say, “Ma, we should have gotten married years ago.” But today, sitting alone, I’m still not so sure.

In the ten busy years that Clark and I went our separate ways, we each had our troubles and our triumphs.

After he was discharged from the Air Force, MGM welcomed him back with open arms, but the wrong kind of scripts.

I was busy handling my own troubles. I really had no burning desire for a film career. After playing a number of bit parts, I turned in my grease paint.

When Clark and I first started dating, it always amused him that my mother was so strict with me. Though I was going on 26 and had been married twice, she still refused to give me my own house key.

Clark would bring me home at 2:00am after some big party and stand there grinning while Mother let me in. Years later, the day after he brought me home to the ranch as his wife, Clark handed me a tiny, beautifully wrapped box. “Your first present,” he said. It was a gold door key. We both laughed, remembering.

Neither Clark nor I took the joking advice we so cheerfully gave each other during that last phone conversation—“don’t get married again.” Late in 1945, I married again. It was not a happy union, but for the sake of our two children, Bunker and Joan, we tried to make it work. After eight years, I sued for divorce. Clark’s marriage to Sylvia Ashley in December of 1949 ended in divorce.

After my divorce, I sold our large Bel Air home and bought a smaller one in Beverly Hills. I had my future all planned. I was going to keep the Beverly Hills house until the children were old enough to go away to school. I don’t recall even thinking about finding happiness—all I asked or sought was an absence of turmoil.

Meanwhile, Clark made his last picture for MGM, Betrayed. He returned to Encino to get another divorce—this one from the studio. After 24 years, Clark and MGM called it quits.

A telephone call brought Clark Gable back into my life. I don’t know what prompted him to dial my number that rainy afternoon in 1954, but when I answered the phone, it seemed as if ten years had suddenly disappeared. “Would you like to have dinner with me?” he asked casually/

Just as lightly I replied, “Maybe you’d find it cheaper to send me the money than take me to dinner. Remember the first time, you had hospital bills for the cook and rugs to be cleaned, and I ended up with china in my knee.”

Clark laughed, then said, “Well old girl, I’ll take a chance if you will.”

We made the date. It was like old times and still it was different. Clark had changed, and I had changed. We had both been matured by trouble and time. At 36 and 53, we were equally determined not to make any more mistakes.

With the exception of the periods when he was away on location, we saw each other every single day for the next year. This time, the excitement and fun were based on a solid foundation. At long last, we were deeply in love.

Often, in discussing some future project, Clark would casually say, “We’ll do this” or “We’ll do that.” But I never once asked him exactly what he meant by that word “we.”

Then, one lovely spring afternoon, Clark and I were sitting beside his pool. “Kathleen,” he said quietly, “don’t you think we’ve known each other long enough—we’ve really been in love so many years. Don’t you think we should get this little job ober with and become Mr. and Mrs.?”

I answered, “I don’t know, darling. I’ll have to think it over. Will you give me five seconds?” he said, “Yes.” And then I said, “Yes.”

We smiled at each other. “Now please propose to me again, darling.” I said. Clark reached for my hand. “Kathleen, will you marry me?”

“Yes,” I repeated.

Clark was a man of great tenderness and understanding. The day we returned to his ranch from our honeymoon, he said, “Kathleen, you don’t have to live here if you don’t want to. We can sell the ranch and buy a house in Bel Air or Beverly Hills or wherever you choose. It doesn’t matter to me—all I want is for you to be happy.”

I looked around the comfortable room, still furnished with pieces Clark and Carole Lombard had selected many years ago. I felt no rivalry with the past. I said, “No, Pa, I want to live right here. We both love the ranch. It’s an ideal place to bring up children. Let’s not ever think of moving.”

I keyed my life entirely to his needs. In the beginning I didn’t really enjoy tramping through some damp field all day, wiggling under barbed wire fences and lugging a gun. But I believe an important part of marriage for a woman is in doing what her husband wants. So I stocked up on hunting clothes, long, warm underwear, slickers and boots, and wherever he went, I went. I learned to shoot and fish and play golf.

During all the time we were married, we got up at 5am. He was never late on the set, and he always knew his lines. Each night, he’d prepare for the next day, going over his script until he was satisfied. Some mornings, he’d still be concerned about a particular scene, so while he was dressing, I’d sit on the bed and, between yawns, cue him.

I rarely visited the set. I saw no reason why I should go to the studio. If I had been married to a banker, I wouldn’t have gone to the bank. He seldom brought home studio problems, and if he did mention something, I never offered advice.

When Bunker started attending a military school, sometimes he didn’t get home until after Clark. He’d come dashing in, hit the back of Pa’s favorite chair, make a leap for Pa’s shoulders and end up balancing on top of them.

I remember one afternoon he really smacked against the chair in executing his running leap. “Now, Bunker,” said Clark, “I have told you fifty, maybe a hundred, times I want you to stop running through the dining room and hitting the back of this chair. You’re breaking it down.”

Bunker jumped to the floor. He looked directly into Clark’s eyes and asked, “Pa, what do you want, broken furniture or a warped personality?” Clark managed to keep a straight face.

When we were first married, Clark had a glassed-in gun cabinet running the length of one wall in the library, which included a neat row of gleaming hunting knives. “I don’t think it’s a good idea to have guns in view of little children,” he said one day. Even though he loved the cabinet, he promptly called in a carpenter to rip it out and replace it with bookshelves.

It didn’t take long for those new shelves to become heavy with books. Clark averaged a book a day, and his taste ranged from Thurber to Thoreau.

One day, Bunker asked Clark what a certain word meant. “Why don’t you look it up in the dictionary?” Pa replied. “Oh, that’s too much trouble, and besides, I’m not sure how to do it,” the boy said.

Clark’s voice was friendly, but firm. “No, son, you must never say it’s too much trouble to learn something. Come on, let’s go look that word up in the dictionary. I’ll show you how.”

Clark took a great interest in helping me plan the children’s future education. One night, when we were discussing prep schools and colleges, Joan asked Pa what college he’d attended. “The college of hard knocks,” he told her.

A few days later, Joan came home and marched up to Pa. “Dearest Stepfather,” she began, “I asked our teacher, and she said there is no such school as the college of hard knocks.”

Clark squinted and raised his eyebrows in that characteristic way of his. But his smile was warm as he took Joan’s hand and replied, “I don’t like to contradict your teacher, Joan, but I’m afraid someday you’ll find out there is.”

The children knew Clark made movies, but they attached no more importance to this than if he had gone to work in a bank or office building. Pa never talked about himself as a star. So they could never quite understand why he attracted so much attention when they were out.

When Bunker joined the Encino Little League, Clark spent many an afternoon practicing with him. After Clark died, Bunker would pick up his baseball and go out all by himself. He’d throw the ball, then run like a deer to catch it. I’d watch from the window, sharing his loneliness. One afternoon, he came in and said, “Mother, I miss Pa so much.”

“Yes,” I said, “we all do.” Bunker fiddled with his mitt for a moment then added, “But I miss him for so many special things. If he were only here to throw me some hot grounders.”

Clark’s delight in Bunker and Joan served to increase his desire for a third child in the family. Two months after we were married, the doctor told me I was pregnant. Pa was so pleased that he just sat there beaming. This was what he wanted more than anything in the world.

During the tenth week of pregnancy, I contracted a virus and suffered terrible pains. One evening, Clark called the doctor, and we went to the hospital. At 4am, the doctor said, “I’m sorry; I’ve done everything possible but I can’t save your baby.” He ordered me to surgery.

When I regained consciousness, I could see that Clark was biting his lower lip hard in an attempt to control his emotions. Finally, Clark managed a weak smile. “There, there, darling, don’t worry,” he consoled me. “We’ll have our baby yet.”

But his comforting prediction didn’t come true for almost six years.

When the new baby was expected, Clark and I spent hours planning his nursery and talking about his future. One day, I brought up the subject of religion. I knew Clark had been baptized a Roman Catholic, his mother’s faith. His father was a Methodist. “What about the baby’s religion?” I asked him.

He didn’t answer the question for several minutes. Then he said, “Well, Kathleen, you were baptized a Catholic, and you’re bringing up Joan and Bunker in the same way. You know more about your religion that I do. So let’s baptize the baby a Catholic. I know you’d like that.”

Clark was always essentially a conservative man. It had been said that he was overly thrifty. This wasn’t quite true. He was not a silly spendthrift, but neither was he stingy.

He did have one weakness—for beautiful, fast sports cars. One he used to look at longingly was a Mercedes 300 SL. He debated with himself for weeks about buying it. He’d take it out on test runs and then come home and freat about it. I said, “Pa, why don’t you get that car you’re so crazy about? You seldom buy anything for yourself, and you’ve worked so hard. You have the money—go get it.” Finally, he did.

One day, he made the supreme gesture. He let me try it. “Let’s see if you have the proper touch for it,” he said. Nervously, I agreed. The car and I fought it out for a block, then Clark rendered the verdict.

“Move over, Ma,” he said. “I love you, but you just don’t have the touch. You’re not driving this car.”

Clark was bronzed, trim and fit when we all left for the Reno location of The Misfits in July, 1960. I had not the slightest hint that these were to be the last five months of his life.

It is painful to recall the frustrations and tensions he endured during those rugged months of filming. But it is a great comfort to remember that it was also during this period that he received word he was to have a child of his own. “My God, Kathleen,” he kept repeating, “it’s a miracle—a miracle. At last, we’re going to have a baby in the house. It will be like starting all over again.”

We started planning for the baby; you’d have thought it was expected the following week. At one point, Pa grinned and said, “Kathleen, you’re 43 and I’m 59. Why, just think, between us we’re 102, and here we are having a baby!”

Once the word was out, reporters hurried to confirm it. Clark, who in the past had always been reticent with the press about personal matters, happily told them it was true. Almost everyone asked whether he wanted a boy or a girl. He always said that he had no preference. But I prayed for a boy, because I knew what a son would mean to Clark.

Most of The Misfits was shot on a blistering hot dry lake bed 50 miles from Reno. The thermometer generally registered 135 degrees by mid-afternoon. Many members of the cast and crew became ill. But Clark outrode and outwalked men half his age. He did take after strenuous take roping a wild stallion singlehanded.

Clark enjoyed hard work, but his own punctuality made it difficult for him to tolerate tardiness. He was the first one to arrive on the set each morning. A disciplined professional, he was always ready to work, always knew his lines. Naturally, it was frustrating for him to spend hours waiting for others.

One evening, I heard Pa yell and dashed in to see what was wrong. “It’s nothing,” he said. But I discovered raw brush burns on one whole side of his body. Clark explained they had filmed a scene in which he was dragged on a rope behind a truck going 30 miles an hour. I was appalled. “Why are you doing those scenes?” I asked. “You’ve got a stunt man who’s supposed to do them.” Clark confessed that he’d found the waiting so demoralizing he’d volunteered to do the scenes just to keep occupied.

The last day Clark spent in the house he loved was Saturday, November 5, 1960. The night before, Clark had finally finished all work on The Misfits . He came home looking so worn out that my heart ached for him.

Saturday morning, he looked more rested. We had breakfast. Then later in the day, Pa took his hunting dog out to one of our back fields and worked him. He was pleased with the dog’s performance, and we talked about future hunting trips. Pa played with Joan and Bunker for a while, but later seemed quite tired and restless—so unlike him. So I said, “Come on, Pa, you had better get a good night’s sleep, so off to bed.”

About 4am, Clark awakened with a bad headache. I gave him some aspirin, and he dozed fitfully. At 8am, I woke to find Clark standing in the doorway. He had started to put on a pair of khakis, but he had been unable to finish dressing. His face was gray and beaded with perspiration.

“Ma, I have a terrible pain,” he said, “It must be indigestion.” I was frightened, but I tried to keep my voice calm as I helped him to a chair.

“I’m calling a doctor,” I said. “No, don’t,” Pa protested, “this will go away in a while. I don’t need a doctor.” I looked at Clark sitting there helplessly, then I reached for the phone. As I dialed, I said, “I’ve never disobeyed you, Pa. But this time, I’m sorry; you must have a doctor.” I knew something about heart conditions, having suffered from angina attacks.

The doctor called for an ambulance and a fire department rescue unit. “Is it a coronary?” I whispered. The doctor said he thought it was.

Clark protested my riding in the ambulance with him; he was afraid it might prove too upsetting in my condition. Of course, I insisted. “I feel terrible, Ma, doing this to you,” he said.

For the next ten days, I rarely left Clark’s bedside. One day, I brought in two little elbow pillows, so he could read more comfortably. Clark looked at me over the top of his reading glasses. “Come on, old lady,” he protested. “Let’s not overdo this. I’m not quite that fragile.”

Pa continued to look forward to the baby. I was five months pregnant then, and he used to say, “Kathleen, stand by my bed sideways—I just want to look at you.” One of my dearest and last memories of my husband was the look of proud anticipation on his face the day we borrowed a stethoscope and he listened to his son’s heartbeat. “You must have Mr. America in there,” he said. Today, when I hold John Clark in my arms, I remind myself that at least Pa had that much.

After Clark’s attack, the doctors explained the tenth day was generally the crucial one for a coronary patient. I went home to gather up some things for Pa. He appeared to be doing well that day. I was determined to be strong for my husband and the child we expected. But as I moved about our bedroom that afternoon gathering up the items Clark had requested, I broke down and wept. Finally, I pulled myself together and hurried back to the hospital.

When I entered his room, Clark looked at me and said, “Oh, God, Ma, don’t leave me again. I don’t want to be alone.”

The next day, Wednesday, November 16, we all felt encouraged. I brought in some of the letters and telegrams that had been arriving by the hundreds each day. Each afternoon, I’d select a small number for Clark to read.

I sat next to Pa’s bed. I had never seen him look so handsome, so serene, in all the years I had known him. The marks of his illness were gone. Clark looked 20 years younger, and his expression was peaceful. I’ve heard it said the flame burns brightest just before it sputters out. But this never crossed my mind as I sat there.

Pa and I had a nice little dinner together. At 10 minutes past 10pm, I felt an angina attack coming on. I couldn’t understand it; I hadn’t had one for nearly two years. I didn’t want Clark to worry, so I quickly made an excuse to leave the room. I kissed him and gave him a tender hug, saying, “Sweetheart, I’ll be back after the nurses get you ready for the night. Then we’ll drink our buttermilk together. I love you.” They were the last words I spoke to my husband.

Over and over, I have said to myself, “Oh, if I only hadn’t left the room.” But at least I know that it was over in a split second. The doctors assured me Clark had suffered no pain; he didn’t know he was dying. The nurse said he simply closed his eyes, his head fell back on the pillow, and he was gone. It happened at exactly 10:50pm.

I had dozed off after going to my room and was awakened by the doctor and a nurse. “Clark has taken a turn for the worse,” I thought I heard the doctor say. The nurse seemed to be crying. I started to get up, then blacked out. In a few seconds, I recovered. The doctor was rubbing my wrists. “What did you say?” I cried. This time I heard him clearly. “Clark has passed on.”

“Let me go to him,” I said, pushing myself up from my bed. “No,” pleaded the doctor. “It’s better for you to stay here.” I reached for my robe. Nothing on this earth could have stopped me from going to Pa. I motioned the doctor aside, and I went.

When I finally returned home, I went straight to Clark’s study and sat in his favorite chair. I had refused any sedatives. I wanted my thinking clear; there was much I must do. I was determined not to let Pa and his baby down. I sat there a long time. It was morning when I finally ordered some tea and sent for the children.

Calmly, but gently, I told Bunker and Joan that Clark was gone. They listened quietly, their faces white. I put my arms around them. “I want you to remember Pa loved you both,” I comforted. “One of the last things he did was to ask me to call home and find out how you were.”

In death, Clark was accorded the dignity and respect he had always earned in life. I am so grateful that nothing married the solemnity of the simple funeral services. Clark had once remarked, after reading a distressing account of a star’s last rites, “Please, Ma, don’t ever let that happen to me. Don’t let them make a circus out of it.”

In making the arrangements, I tried to carry out Clark’s every wish. I buried my husband in his blue wedding suit and with his gold wedding band and his St. Jude medal, his last Christmas gift from Bunker and Joan.

In the trying and lonely days that followed, one thought was uppermost in my mind—the birth of Clark’s child. The loss of my husband was shattering, and the tragedy that he would never hold his baby almost defeated me at times. But I was determined not to give in to grief. I owed it to Pa to carry on sensibly and calmly, making sure nothing went wrong in those last four months.

John Clark Gable was born in the same hospital where his father died 124 days before. I dreaded returning to that building, but my obstetrician, who had delivered Bunker and Joan, and in whom Pa and I had great faith, was on the staff there. The birth was to be by Caesarean section, and my doctor preferred operating with his own surgical team. I watched the birth in the reflection of the big light fixture above me. My first words when I saw my son were, “He’s beautiful. Just what Pa wanted.”

Later, when the brought the baby to me in my room, I struggled to keep my emotions under control. This was the moment that Clark had so eagerly anticipated. Here at last was his beautiful 8 pound son—the dividend he didn’t live to enjoy.

I examined my baby closely; he was absolutely perfect. Then I said his name out loud—John Clark Gable. It had been Pa’s choice. It is hard to put into words my feelings as I held our son that first day. How can you describe such a strange mixture of grief and gratitude, of unbearable sadness and great joy?

John Clark has brightened our home, and the love that surrounds that dear little boy gives each day more meaning. His nursery is the happiest room in the house, and although Clark’s presence is everywhere, I seem to feel it most in there. Pa helped plan the room, even to choosing the colors. Often, as I stand beside John’s bed, I am sure that my husband is standing there with me, his smile as proud as mine.

I will always sorrow for Clark. But I will always find comfort in the remembrance of his love. And now I have his son. God blessed me very well.

3 Comments

Margaret

Very enjoyable article and made me well up at the end. It seemed that Clark and Kay were very much in love and in a happy marriage when he so sadly passed on. Lovely to hear about him from his wife who you can tell adored him. It must have been horrific for her to lose such a wonderful man but she did what he would have wanted and got on with her life and had little john Clark.

Kay seemed like a lovely lady and you can tell from how she describes their marriage that they were a well matched couple. You can also tell she is a very intelligent lady the way she reflects back on their life together.

Pam

Very enjoyable read. So sad they didnt have more happy years together.

Margaret pokorny

Ditto ladies.