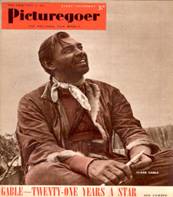

1951: Gable–Still at the Top

by Stephen Watts

Picturegoer, October 20, 1951

From a plain tough screen-lover, to an Oscar-winner, to the mature, fifty-year-old Clark Gable of today. With his latest picture, Across the Wide Missouri, Gable’s acting line stretches over twenty-one years of top-peg stardom…Stephen Watts traces its surprising course.

Remember the lyric from Cole Porter’s “Always True to You in My Fashion” from the current stage hit, ‘Kiss me Kate”? Here’s a snatch to refresh your memory: “Mr. Gable, I mean Clark, Wants me on his boat to park. If a Gable boat means a sable coat…anchors aweigh”.

They are, in their way, significant. The glamorous girl who sings the song is cataloguing the irresistible temptations that might come a girl’s way. And to personify the tops in masculine attraction in the year 1951 who is cited?

None other than the fifty-year-old, rugged, graying William Clark Gable, now celebrating his majority as a world-famous film star, and who will be seen next in Across the Wide Missouri.

Twenty-one years non-stop as a romantic idol—and they say the film public is fickle!

More than a decade ago it was a schoolgirlish Judy Garland staring rapturously at a photograph and singing “Dear Mr. Gable…” The melody changes but the theme lingers on.

Nobody is more surprised—or more modest—about this persistent phenomenon than Gable himself. Nearly twenty years ago he said: “Five more years and then I quit and start to enjoy myself. “

A little later it was: “At forty I retire…” Instead, when he was forty there was a war on in Europe and Gable, qualified pilot and man of action, was in it before he was a year older.

Then—A Flop!

Such was the power of his fame that his enlistment was described as “the best propaganda the Army has ever had.”

After demobilization he came back to films. His return film was Adventure with Greer Garson—a flop. He survived it.

And look at the record as it stands now: twelve consecutive years in the top ten most popular stars, a unique achievement, forty-six pictures which have brought an estimated 70,00,000 to the box office, a best actor Oscar, a fan mail which never dropped below 2,000 letters a week even while he was away in the Army, more proposals of marriage by mail than any living man, and co-star with all the screen’s most celebrated women from Marion Davies and Colbert, Jean Harlow and Norma Shearer up to the “moderns’ such as Lana Turner and Deborah Kerr.

It was a Hollywood café philosopher who said reflectively of Gable: “And to think a studio once turned him down on a test because his ears were too big. Now they’d give Their ears just to peddle pictures of his.”

The man behind all this is a genuinely simple character—a mid-Westerner who has never been tempted to become a city slicker.

The Gable career has passed through several phases. At first it was imply his looks and physique which appealed. He arrived at a time when the screen (and, consciously or not, picturegoers) were crying out for new men.

One type was supplied by Cagney, the other by Gable. It was the Gable type that had romance as well as brusqueness and a strong right arm. Nobody thought of Gable as an actor, but he drew women into the cinemas.

The shoulders, the dimple, the slightly sardonic, twisted grin alternating with the scowl—those were enough to go on.

The story is told that when, in an early film, Gable was required to produce a sudden expression as he swung round. Apocryphal, maybe, but there is no doubt that it was only as he developed confidence and familiarized himself with screen technique that Gable passed into his second phase—as an actor.

Personality was still his strong suit, but now came genuine character-creation. I agree with the critic who said about them that even in a dullish film Gable always contrived personally to hold attention—“you are content to wait for the next interesting episode because you trust and like and are absorbed in the character.”

The next phase—perhaps the decisive one in the formation of the Gable we know—was the revelation of comedy ability. A shy man, Gable heard with dismay that his home studio has loaned him out to Columbia.

He heard, too, that the film has been originally written for Robert Montgomery. He was so surly when he first met the director, Frank Capra, that Capra called the studio chief and complained that he’d never get a performance out of a man who so clearly wasn’t enthusiastic.

No Flash in the Pan

But the next day Gable was all smiles and apologies. He had read the script and saw new opportunities for himself. The film was It Happened One Night, one of the most delightful comedies every made, It was for this film that Gable got his well-earned Oscar.

That this acting skill was no flash in the pan has been amply demonstrated since, to name only the solid acting performances of Mutiny on the Bounty, Parnell, Idiot’s Delight, San Francisco and Gone with the Wind.

If Gable came in with the gangster era he had travelled a long way from it by the time of Gone with the Wind. Here was one of the richest parts ever written for an actor—romantic, dramatic, ranging widely in mood, the two-fisted adventurer who could be Don Juan and also an adoring husband and father.

By this time Gable was in phase four—the mature Gable, his facial lines improving rather than detracting from his looks, his relaxed strength and easy, experienced screen technique giving his performances and added solidity and authority. But still the same Gable, measuring up as much as the day he began to the description of his debut as “the new kind of lover—virile, a little brutal, 100 percent he-man.”

The Gable appeal has always been predominately to women, but men like him because he is a man. The thing he hates most is too much stress on his romantic appeal.

“How does it feel to be the world’s greatest lover?” asked a gushing woman reporter at one of those goldfish-bowl receptions where people say such things. Gable looked at her steadily, with a grave, quizzical eye for a moment, and then he spoke quietly: “It’s a living,” he said.