1934: Success Hasn’t Turned His Head

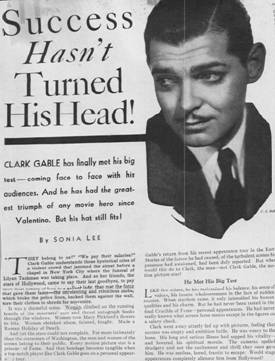

Success Hasn’t Turned His Head

By Sonia Lee

Unknown publication, 1934

Clark Gable has finally met his big test—coming face to face with his audiences. And he has had the greatest triumph of any movie hero since Valentino. But his hat still fits!

“They belong to us!” “We pay their salaries!” Clark Gable understand those hysterical cries of a violent crowd that jammed the street before a chapel in New York City where the funeral of Lilyan Tashman was taking place. And as her friends, the stars of Hollywood, came to say their last goodbyes, to pay their final tribute of love to a gallant lady, they met the force that gave them fame–the unrelenting and relentless mobs, which broke the police lines, backed them against the wall, tore their clothes to shreds for souvenirs.

It was a shameful scene. Women climbed on the running boards of the mourners’ cars and thrust autograph books through the windows. Women tore Mary Pickford’s flowers to bit. Women shrieked abuse, fainted, fought. Made a Roman Holiday of Death.

And yet the stars could not complain. For more intimately that the statesmen of Washington, the men and women of the screen belong to their public. Every motion picture star is a prisoner of Fame. And that bondage becomes tangible when a top-notch player like Clark Gable goes in a personal appearance tour.

With greater interest than customary, Hollywood awaited Gable’s return from his recent appearance tour in the East. Stories of the furor he had caused, of the turbulent scenes his presence had awakened, had been duly reported. But what would this do to Clark, the man—not Clark Gable, the motion picture star?

He Met His Big Test

Like few others, he has maintained his balance, his sense of values, his innate wholesomeness in the face of sudden success. When stardom came, it only intensified his human qualities and his charm. But he had never been tested in the final Crucible of Fame—personal experiences. He had never really known what screen fame means except in the figures on a salary check.

Clark went away utterly fed up with pictures, feeling that success was empty and ambition futile. He was weary to the bone. His long and serious illness had sapped his vitality—and lowered his spiritual morale. The cameras spelled drudgery and not the excitement and thrill they once gave him. He was restless, bored, frantic to escape. Would stage appearances alienate him from Hollywood?

Strangely enough, contrary to expectations, he came back bright, alert, on his toes! He was rejuvenated and vitalized by a new eagerness. His public had sent back a new Clark—a greater man, and potentially, a greater star! And wearing the same size hat.

What happened to Gable in the few weeks during which his public claimed him for their own?

He says very seriously: “I’ve been given courage to go on. Have I changed in any way because a little fuss has been made over me? No, I don’t think so. As near as I can tell, by every test a man can give himself. I haven’t changed at all. I am long past the stage where I get a swelled head over a little attention.”

He’s All Pepped Up Again

“My personal appearance tour has been an inspiration. It has given me new zest—almost a new strength. It is gratifying to see hundreds of people show approval for my ‘futile’ efforts. I’ve got a new sense of values from the experience. It is worthwhile to go on, to do the best I can, because the public expects that of me.

“A star, as a person, is not important. This week it happens to be Gable who gets the attention. Next week it’s someone else.

“I’ve learned a lot in the weeks I was East, meeting, face to face, the people to whose favor I owe so much. I know if you let audiences down—if your performance is slip-shod—if you don’t give them your best, they sense it and resent it.

“I’ve learned conclusively that no star is better than his last picture. I tested that theory. I asked audiences which of my pictures they liked best. There was a patter of applause for ‘Red Dust.’ A bit more for ‘Hold Your Man.’ But there was a thunder when I mentioned ‘Dancing Lady.’”(“It Happened One Night,” the picture that many claim is Clark’s best, had just been released—too recently for widespread audience reaction then.) “A star stands or falls for his current picture. If it’s a flop—he’s a flop. If it’s successful, then he continues in favor. You can’t live on past laurels.

How People Want to See Stars

“I’ve discovered that audiences resent all-star casts. They want to see their favorites do something—in effect, run the gamut of emotion. If a star only has a bit to do, then audiences feel cheated. They don’t want to see a dozen stars do something inconsequential. They prefer a single, vivid, clean-cut performance. Audiences aren’t bargain-hunting—they are satisfied to see one star for the price of one admission.

“I’ve learned a lot of things in the two weeks I was gone—and even if I’ve had to buy a few new neckties, and a lot of new handkerchiefs—even if the tailor has been kept busy replacing buttons on my clothes—it has been more than worthwhile.”

Gable excited an emotional frenzy comparable to the uproar that followed Valentino. If ever a man was given tangible proof of the regard in which his public held him, that man is Gable.

In Syracuse, New York, the Mayor and the City Council and ten thousand clamoring citizens met his train.

In Kansas City, when he was again Westbound, he agreed to make a personal appearance at a local theatre. The train had a half-hour’s stop before proceeding, and it was thought ample time to give him a chance to drive to the theatre and to return. But even before the train came to a halt, thousands broke through police lines and rushed the platforms. He was forcibly pulled out of his car—a wildly cheering, emotional mob paid homage to a hero!

He did make his personal appearance. The train, however, was delayed for a good half-hour additional, and a week later, the railroad station still showed physical evidence of the mob’s frenzy.

The Welcome New York Gave Him

His arrival in New York was heralded by a most amazing exhibit if devotion, His train came in at an hour when stenographers were at their desks, clerks behind their counters, and housewives, presumably, still wielding their brooms. Yet the Grand Central Terminal was dark with thousands. A flying wedge of policemen and red-caps was formed to rescue him from the clamorous mob. For a half-hour his automobile couldn’t move an inch. Neither entreaties nor threats could budge the squealing, shouting, boisterous crowd that sought to touch him—to get within sight of his face and sound of his voice.

A completely disheveled Clark, with every button missing from his overcoat, suit coat and vest, finally was delivered at his hotel. It was a new experience for him—and a stimulating one. It was like an electric treatment.

Everywhere he went in New York, he stopped traffic, He attended Helen Hayes’ performance of “Mary of Scotland”—and was discovered by the audience during intermission. For a while it seemed to the company managers that the play could not resume—and they seriously considered refunding admissions to those in attendance. For fifteen minutes the second curtain was delayed, while the hundreds present paid tribute to Clark Gable.

During his week of New York personal appearances, he was virtually held prisoner in the theater for eighteen hours out of every twenty-four. He came early—long before the box-office opened—and yet never so early that he didn’t find a solid wedge of men, women and children at the stage door.

Mobs Kept Him Prisoner

Clark never dared to go out between performances. His lunch and dinner were brought to his dressing room. Yet even there his fans found him out. There was a fire escape—offering a treacherous ascent to his window. And, invariably, there were faces peering in at him behind the locked window.

Long after the house lights were darkened, Clark Gable would be whisked out a side exit—rushed into a taxicab for the few precious hours of freedom. But even in his hotel suite with Mrs. Gable he had no privacy. Women sought him out.

The scenes in New York had their counterpart in Baltimore. Handkerchiefs were snatched out of his pockets, buttons were torn off his overcoat, and one courageous soul went so far as to snip a lock of his hair. On his first night in the Maryland city, he didn’t dare go to his hotel. After cruising in his taxicab, waiting for the mobs to disperse the lobbies and the sidewalks, studio and theatre representatives finally took him to another hotel.

Clark Gable is back from shaking hands with his public. Forever after this, his salary check will not be his only measure of his success. He will remember—perhaps with a shudder—the press of frantic bodies, the clutch of possessive hands, the glare of eyes hungry for something lacking in life, seeking to find satisfaction, romance, adventure in a motion picture hero. He will know with awed pity that he must be to love-starved women in the Lover they have dreamed of: to people caught in the struggle for daily bread, the embodiment of the Dream they once dreamed. And this knowledge and responsibility will make him a better actor and a greater man.