1933: Lost–The Gable Wallop

Lost—The Gable Wallop

By Samuel Richard Mook

Picture Play magazine, August 1933

Clark sits up through the night and thinks about himself. Has too much introspection robbed him of his force and punch?

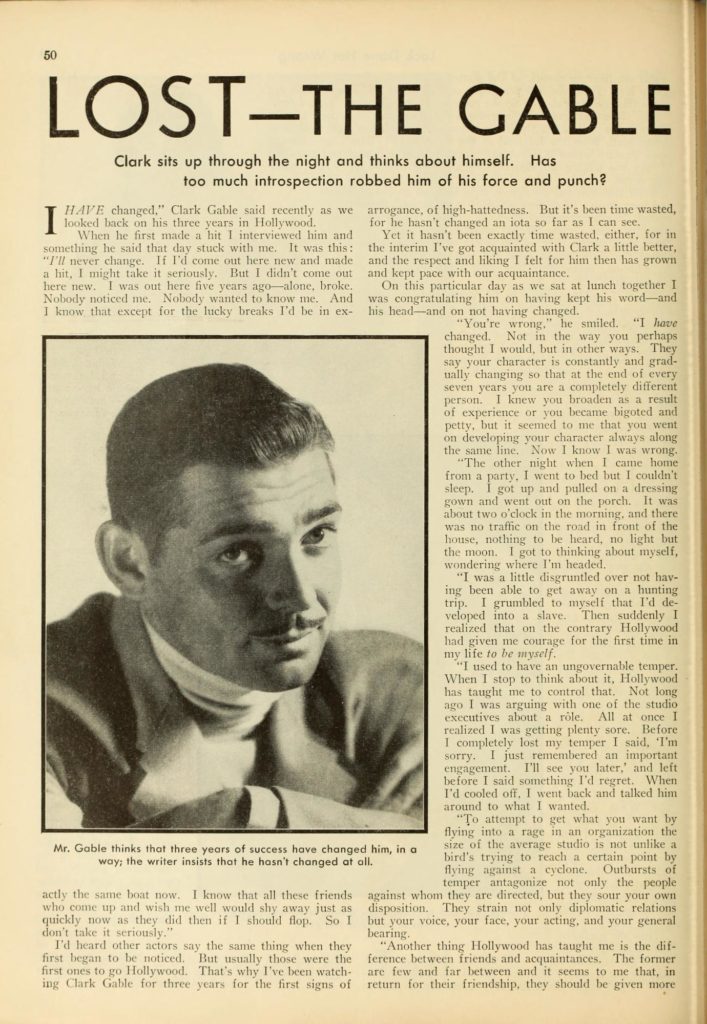

“I have changed,” Clark Gable said recently as we looked back on his three years in Hollywood.

When he first made a hit, I interviewed him and something he said that stuck with me. It was this: “I’ll never change. If I’d come out here new and made a bit, I might take it seriously. But I didn’t come out here new. I was out here five years ago—alone, broke. Nobody noticed me. Nobody wanted to know me. And I know that except for the lucky breaks I’d be in exactly the same boat now. I know all these friends who come up and wish me well would shy away just as quickly now as they did then if I should flop. So I didn’t take it seriously.”

I’d heard other actors say the same thing when they first began to be noticed. But usually those were the first ones to go Hollywood. That’s why I’ve been watching Clark Gable for three years for the first signs of arrogance, of high-hattedness. But it’s been time wasted, for he hasn’t changed an iota so far as I can see.

Yet it hasn’t been exactly time wasted, either, for in the interim I’ve got acquainted with Clark a little better, and the respect and liking I felt for him then has grown and kept pace with our acquaintance.

On this particular day as we sat at lunch together I was congratulating him on having kept his word—and his head—and on not having changed.

“You’re wrong,” he smiled. “I have changed. Not in the way you perhaps thought I would, but in other ways. They say your character is constantly and gradually changing so that at the end of every seven years you are a completely different person. I knew you broaden as a result of experience or you became bigoted and petty, but it seemed to me that you went on developing your character always along the same line. Now I know I was wrong.

“The other night when I came home from a party, I went to bed but I couldn’t sleep. I got up and pulled on a dressing gown and went out on the porch. It was about two o’clock in the morning, and there was no traffic on the road in front of the house, nothing to be heard, no light but moon. I got to thinking about myself, wondering where I’m headed.

“I was a little disgruntled over not having been able to get away on a hunting trip. I grumbled to myself hat I’d developed into a slave. Then suddenly I realized that on the contrary Hollywood had given me courage for the first time in my life to be myself.

“I used to have an ungovernable temper. When I stop to think about it, Hollywood has taught me to control that. Not long ago I was arguing with one of the studio executives about a role. All at once I realized I was getting plenty sore. Before I completely lost my temper, I said, ‘I’m sorry. I just remembered an important engagement. I’ll see you later.’ And left before I said something I’d regret. When I’d cooled off, I went back and talked him around to what I wanted.

“To attempt to get what you want by flying into a rage in an organization the size of the average studio is not unlike a bird’s trying to reach a certain point by flying against a cyclone. Outbursts of temper antagonize not only the people against whom they are directed, but they sour your own disposition. They strain not only diplomatic relations but your voice, your face, your acting, and your general bearing.

“Another thing Hollywood has taught me is the difference between friends and acquaintances. The former are few and far between and it seems to me that, in return for their friendship, they should be given more consideration and thought than you give your acquaintances. The idea of a smile and a handshake for everybody is the bunk. A little respect and consideration impresses them and enables you to save affection for your friends.

“I know there are some very fine people out here, but I think the majority are more fickle, more changeable, than elsewhere.”

I interrupted for a moment. “I wonder,” I suggested, “if it isn’t because they don’t dare be genuine. They can only afford to know you as long as you’re on top. If two people are friends and one of them does something to offend the heads of the studio and is put in the dog house as a result, wouldn’t it jeopardize the other’s standing at the studio to be seen around with him too much?”

“To hell with that sort of thing,” Clark exploded. “I’m going to be friends with whom I please, regardless of what other people think. I don’t give a tinker’s dam about whether friendship is expedient or not. I’m going to stick to the people I like and who amuse me.

“I think probably the greatest thing Hollywood has taught me is that—for me, anyhow—the best things in life are the simplest. I go to parties occasionally, but when I’m through at the studio it isn’t parties and picture people I think of. I don’t yearn for the Grove or the Mayfair. I want to get as far away from all that as possible. My closest friends are ones who have no connection with pictures.

“One of the swellest times I’ve ever had in my life was on my last hunting trip. My companion was a man who has never seen me on the screen.”

“Didn’t you feel hurt because he hadn’t?” I inquired curiously.

“Lord, no! I loved him for it. When I go out anywhere and people start trying to get me to talk about myself, that’s when I never want to go back to that place again. I find out what business my host is in and then try to discuss that intelligently with him—partly because I’m really interested in other lines of work and partly because it’s the easiest way to bridge the gap. My hunting companion could talk to me about how he keeps his dogs in condition, how lions live, how he goes about trapping animals, and all the other things I love to hear about.

“That sort of thing helps to keep my perspective. I stay in a place like the Kaibab Forest in Arizona for a couple of weeks where I neither see nor hear about pictures, and then I come back with a fresh viewpoint.

“Another thing that I’ve learned is to keep dislikes and disappointments under my hat. Maybe one of the reasons we like dogs so much is because when they’re sick or hurt they always go off by themselves. When they’re around they always put their best foot forward. There’s more real affection in those grand little fellows than in all the stars in Hollywood.

“Formerly when I had a disappointment or heartbreak, I always looked around for somebody to tell it to. Then I noticed that didn’t seem to do me much good and it made my listener feel bad. That started me thinking. To begin with, you can usually get yourself out of your own mess better than any one else can, for you know what you put into it and he doesn’t.

“I recalled my own feelings when I had had to listen to other people’s sob stories. Unless they were very close friends, I was usually embarrassed by their confidences. Often, I was surprised and disappointed over the revelation of some weakness in their characters I had not known was there. And sometimes they would be so regretful later for having exposed themselves, it would seriously impair our future relationship.

“Add to this the undoubted power inscrutability lends any personality and you can see why I’ve tried hard to learn this lesson.”

Clark looked at his watch and jumped up. “I’ve got to show up a moment at a luncheon Mr. Mayer is giving the Japanese navy. Got enough for your yarn?”

It was my turn to smile. Three years ago it was the same thing. We had been talking when suddenly he jumped up and excused himself to have some pictures taken with a horse. And he had been just as anxious then as now to know if I had got enough for my story.

No, despite what he says, Clark hasn’t changed. He learns, but he doesn’t change. And he never will, either, except for the better.