1952: Gable’s in Love Again!

By Elsa Maxwell

Photoplay, October 1952

You know what happens to women—practically all women—every time Clark Gable’s name is mentioned. It would be futile for me to deny that my own reactions follow the pattern. When I arrived in Paris this year and heard Clark was in town, prior to going to London to make his first picture there, I wanted to see him as soon as possible.

Naturally, then, when Anita Loos phoned me one day and asked me to join her for lunch with Clark, I lost no time in accepting her invitation. I met him at the Hotel Lancaster where he was staying and where many of the stars live while in Paris and I was completely delighted.

I saw a new Clark Gable—younger, more handsome than ever, radiating happiness. The first thing I said was, “Clark, you’re looking marvelous!”

“Why not, Elsa!” he exclaimed. And he smiled that inimitable Gable smile. “I’m as free as the air again. I’ve never been happier in my life. And I know now for certain that I shall never marry again.”

Over lunch, he exuded charm and his own rare brand of vitality.

“This is the perfect life,” he said. “Nobody bothers me. Nobody follows me. Most people here don’t even know who I am—and if they do, they don’t care.” Paris is much too polite to bother a King—even the King of Hollywood.

His face was a wreath of smiles when he floored me with his next pronouncement. “Elsa, there’s something terribly important I want you to know.” He paused dramatically. “I’m in love again. Desperately in love.”

“Who is she?” I gasped. My surprise was real, because I had distinctly heard him just a few minutes before vow that he would never re-marry.

“I’m in love with Paris,” he murmured dreamily. “With the Paris that you adore. And what woman could ever compare with her?”

Clark had only allowed himself three weeks in Paris. But his infatuation for the fabulous town gripped him so firmly that he put off going to London to begin shooting on MGM’s “Never Let Me Go” until the very last minute.

And now he says he’s heading back to la belle France whenever he gets the chance.

He doesn’t care though if he never learns to speak a word of French. He’s having too much fun letting the French people explain themselves to him. He can’t even pay his taxi fares without help, so he strikes up a close friendship with every cabbie he encounters. He thinks they’re all terrific; they reciprocate heartily. When he steps out of a Paris cab—no limousines, these rackety, shaky, pre-two-war buggies—the pomp and ceremony is sensational.

First he pays the driver. Then they shake hands. Then they both bow solemnly like Alphonse and Gaston. Then they shake hands again. Toujours la politesse. I wouldn’t be surprised to see Clark get a big kiss on each cheek from a French charioteer one day, in the fine French style reserved for military heroes being awarded medals.

Clark had a charming dinner companion almost every evening during his stay in Paris—Virginia Keeley, a lady who might come closer than most to winning his attention away from the fascinating old town. Virginia, who looks startingly like Carole Lombard, is not an actress. She’s young and gay, with blonde hair blowing in the breeze—just a girl from home.

Seeing Clark again in Paris—assured, relaxed, very much at peace with himself and his world—I was struck with how little he has really changed since I met him in 1932. He’s more sophisticated, worldlier, yes, But the basic sweetness and simplicity are the same.

When I first saw him, way back in his early Hollywood days, I thought he was not only the handsomest man I had ever seen, but also the shyest. He seemed unaware of his charm. When all the great stars get together at parties, Clark always stayed on the outer fringe—a little awkward, ill at ease, not quite sure of himself.

The first time he seemed to break out of his shell and join the general festivity was one night at a party where he swung into an old-fashioned barber shop quartet with the late Leslie Howard, Gary Cooper and Ronald Colman. Everybody loved it. There was a great deal of good-humored chaffing—and Clark, for once, seemed freed of his restraint.

This was just about the time that he was being divorced from his second wife, Rhea, a charming woman much older than himself. And it was probably the fact that he was solving his marital problems that contributed to his general ease…comparative ease, that is.

But he never became a real social butterfly in any sense of the word. I saw a great deal of him during that period, and I knew him to be a man of few words. He was already the greatest male star in Hollywood; but he hated public adulation. Autograph hounds upset him and he rarely even attended his own premieres. What he wanted most was to be left alone. MGM provided him with ironclad protection and the result was that few people saw him.

I remember his particularly modest behavior after his huge success with Claudette Colbert in “It Happened One Night.” Claudette gave a party to celebrate, and although Clark came—it would have been rude not to—he left almost immediately. There were too many people, too much praise for his taste.

The famous Garbo line would have been just as accurate for Gable as it was for the fabulous Swede. More than anything else, he wanted to be alone. He wanted to hunt, to fish, to break his way through bush-tangled paths. And he neither searched for nor seemed to desire any feminine companionship on these masculine forays.

Until he met the late Carole Lombard. She strode into his life with easy assurance. In her breezy, fun-loving, free-wheeling way, she was the perfect complement to him. And she adored him. When they were married, she chose to key her life entirely to his needs, his enthusiasms, to place her career second to his.

Their life together seemed to be enclosed in a magic circle—so tightly drawn that no outside could step into it at all. They turned their backs squarely on Hollywood’s social life, which came as a surprise to people who knew them. Because Carole, at least, had loved the flurry and excitement of filmdom’s parties.

They moved out to Clark’s ranch in the San Fernando Valley and turned it into a sort of shrine to their happiness. I remember when I first went out there being almost overwhelmed by the way Clark—the man’s man—had turned his hideaway over to his wife. He had hung a huge portrait of Carole in his gun room—his own special retreat—and there was another painting of her in the drawing room. Her face and her personality were everywhere in that house.

Yet, I sometimes have the feeling that even before Carole’s tragic death, their romance had begun to wear just a little thin. Carole was the pal—the good companion in every way, one of the boys—but I think Clark was beginning to yearn for more real femininity, for a gentler, womanlier wife.

Clark was truly grief-stricken though when news reached him of the plane crash in which Carole perished. And after that, he withdrew more completely into his shell than ever before.

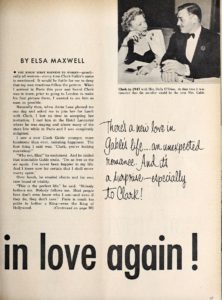

But always, somehow, there seemed to be one human being destined to pierce his armadillo covering. This time it was Mrs. Dolly O’Brien—charming, blonde, beautiful. She had a wonderful house in Palm Beach in which she gave fashionable parties. But Clark would never visit there during the season. Too many people, too much adulation. But he did come East to see her every year after the holidaying birds had flown north. They seemed very attached. I thought they might marry, and once I asked Dolly about it.

“Never,” she said firmly. “I would have to live in Hollywood. Can’t you just see me standing meekly in the background while Clark signed autographs?” She laughed a little. “Oh, I’m fond of him all right. But just being Mrs. Clark Gable isn’t good enough.”

Their romance ended—interestingly enough—in France. That was four years ago. It’s strange, seeing Clark so enchanted by Paris now, to think that he was unhappy there before. But he was. His only memories up till then of the country had been rigorous, unpleasant ones—the result of his war experiences. And to make it worse, he wasn’t well when he was there with Dolly. He had a touch of arthritis in his leg, and though he played some golf with the Duke of Windsor, he was disgruntled most of the time. When news of his father’s death in the States reached him, he left France and Dolly behind. And I think he was glad to go.

Dolly married again shortly afterwards. And that was the end of that.

Through this long trying period, my friendship with Clark continued firm and strong. My affection for him grew, and I was genuinely concerned about this paradoxical man who, though at the very top of his profession, was lonely and unhappy.

Then three years ago, I gave a ball in New York, where I was inaugurating square dancing for the sophisticated Manhattanites. Dolly wasn’t remarried at that time, and she brought Clark to my party. And what a job we both had convincing him to come!

I was calling routines over the microphone, and when I noticed that Clark and Dolly weren’t dancing, I determined to find him a partner. So I beckoned to Lady Sylvia Ashley—she was then Sylvia Fairbanks—to take him in hand. She got up to dance with him, and I think it was the first time they had exchanged more than polite “How do you do’s” though they had met before through Dolly.

Sylvia looked particularly lovely that night and Clark was really quite gay. It was obvious that they had something for each other. But nothing much came of it then, because Sylvia had to leave for California the very next morning. She had some business affairs to take care of—matters that had to do with the estate she had inherited from Douglas Fairbanks. Even if she had wanted to stay, she couldn’t have.

That winter, however, they did see each other fairly regularly in Hollywood. I saw them dining together several times at Romanoff’s, and it was apparent that Clark found her gay and amusing. She’s a man’s woman, there’s no doubt of that.

And she had a way of setting Clark back on his heels, blithely letting him pursue her. He admitted to me that it was this independence of hers—this casual rejection of his favors—that started him thinking seriously about her. It was a little pettish, like a child who doesn’t want any toy except the one he can’t have. But that was how it developed. And I suppose that’s Clark.

Soon they were seeing each other constantly. Through their wedding—and their honeymoon trip to Honolulu—came as a surprise jolt to Hollywood, the step was inevitable for Clark. The feminine Sylvia enchanted him completely.

When I saw them after their return to Hollywood, Clark took me aside and confessed to me that he was deeply in love.

“Elsa,” he said, “I don’t know about English women. But I’ve heard a lot and read a lot about sirens. And now that I know Sylvia I’m convinced that sirens are an export product of the British Isles.”

It looked and sounded very hopeful to me. I would see them again and again, and the radiant glow never diminished. I remember once discussing marriage with Greta Garbo at a party at Cole Porter’s house in Brentwood. We had been talking about why Garbo had never married, when Clark and Sylvia walked across the room. Garbo gazed long and hard at the glowing Mrs. Gable, and then turned to me with a touch of sadness in her eyes.

“If I thought I could ever be as happy as she is, I would look on marriage in a new light.”

There seemed no doubt at all that everything was going beautifully between my friend and his bride. I had seen them blissful together when I dined alone with them at the San Fernando ranch. And I couldn’t help noticing, of course, how every trace of Carole Lombard was gone from the house, and how Sylvia’s brand of womanliness now dominated it. She had turned a rather austere bachelor abode into a gracious and charming home—flower-filled, elegantly decorated.

Nothing could have shaken me from my belief that this was a real marriage, permanent and lasting, when I tool my leave of them in Hollywood. So I was completely startled when news of the break came. It was common knowledge that Sylvia had flown to Nassau, but we had all believed that she had simply gone to see to the disposition of some joint property there. It was invoiceable that this could have been the prelude to their final parting.

But it was. And the rest is history.

What really happened, nobody knows for sure. But Sylvia told me that there was far more unhappiness in their marriage than anyone would ever have dreamed.

For one thing, Clark refused to allow her to visit him on the lot, because he felt wives shouldn’t be involved in their husbands’ work. And he was moody. Sometimes, when he came home from work, he would go to his room without addressing a single word to her, and then stay behind locked doors for twenty-four hours at a stretch.

The climax came when Sylvia flew back from Nassau and found the doors of the ranch locked and her trunks awaiting her out in the courtyard.

It is a peculiar story. And I wanted to reserve judgement until after I spoke with Clark. But he is reluctant to discuss it.

I do know, though, that while Sylvia was terribly hurt, she was glad to write finis to the humiliating experience of being an unwanted wife.

In any case, the final chapter was written amicably. When she was in the hospital—after the Nassau automobile accident in which she fractured her leg and her ankle—Clark came to visit her, and was more than solicitous. He sent books and flowers, and his concern appeared sincere.

Now it’s all over. Sylvia came out of it with a generous settlement—ten percent of Clark’s earning for the next five years. Since he’s the highest paid actor on the screen, that should be a fat sum indeed.

And Clark came out of it with what seems to be a new and healthier and happier point of view than he has ever had before.

He is hard at work now in London on “Never Let Me Go.” Then he goes on to South Africa to make a John Ford picture burlesquing the typical African safari. But in between times, and afterwards, he’s going to be heading back to Paris just as often as he can.

This romance—his romance with the city that has captivated poets and dreamers for centuries—he will not let die.