1947: Tee for Two

By Ed Sullivan

Modern Screen, November 1947

Golfing with a guy, you find out things; you take the measure of a man. And according to our Ed, Gable’s a gent, a scholar, and a heck of a fellow with a hole in one!

“Sure, it’s been lonely for me,” agreed Clark Gable. “Losing Carole left a gap in my life 1,000 miles wide; it was as though the best part of me died. It’s been pretty tough since then.”

He sipped at his Tom Collins.

“They say it never rains but it pours. On the plane with Carole was a very close friend of ours, Otto Winkler, who was assigned as my publicity man at MGM. I liked him tremendously, relied upon his advice and perception. He died with her. Then I had another friend, Harry Fleischmann. We used to go on fishing trips together. A few months later, he died, so there were three deaths within a space of a few months that wiped out the core of my existence. It hasn’t been easy to reconstruct it, but I’ve done the best I knew how.”

We were sitting in the grill of the Bel Air Country Club, after finishing a round of golf with Major Clark Hardwicke, World War II veteran of the Air Corps, and Bert Allenberg, Gable’s manager. Allenberg and I had just been beaten 4 and 3 by the two Clarks, and I had just paid off my $45 to Hardwicke.

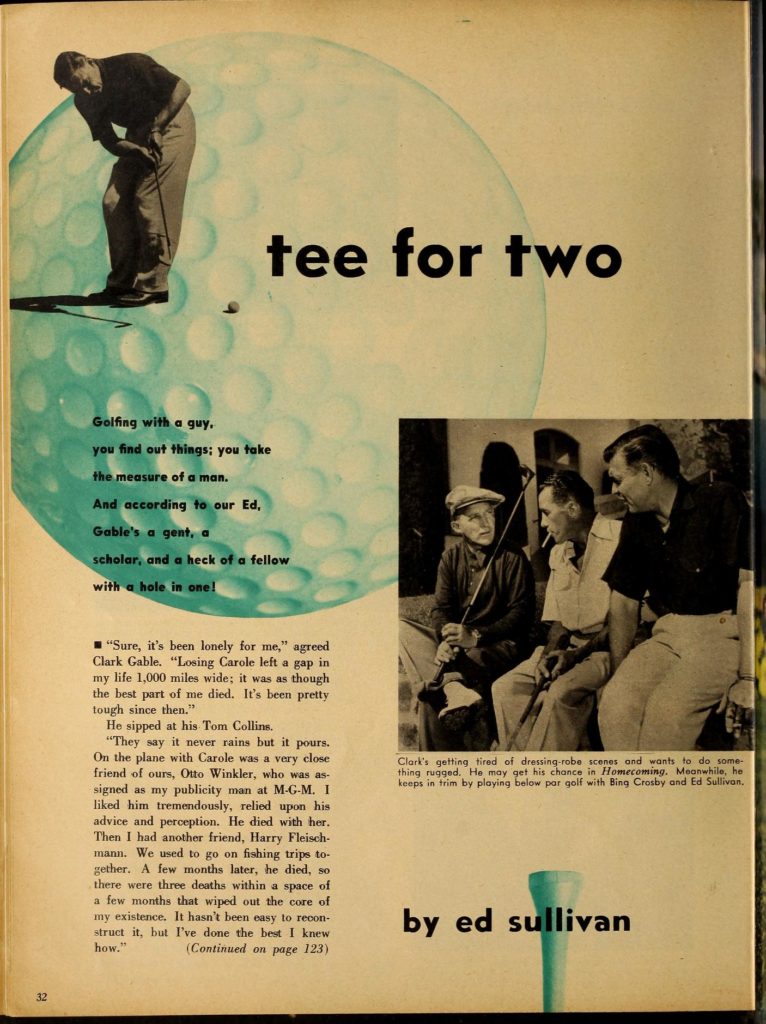

At a nearby table sat Bing Crosby, another fabulous Air Corps golfer, Ken Rogers, Frank Ross, Reginald Owen and the Bel Air pro, Joe Novak. Workmen, perched on platforms near the ceiling of the grill, gave it a real Hollywood studio effect. All that was missing was Cecil B. DeMille, perched on a boom, calling out: “Quiet, please!”

The workmen were soundproofing the ceiling.

“Bert is one of my closest friends,” said Clark, indicating Allenberg, who was absorbed in rolling dice for the drinks with Hardwicke. “Then there’s Al Menasco, who designs airplane engines. We kicked around together for years, but Al got married and you know how it is. A married man just naturally acquires responsibilities, no longer is available for impromptu trips—”

The Modern Screen photographer, Don Ornitz, came into the grill and said that he had gotten his color film equipment out of his jeep and had to set it up on the 10th tee, for one last shot of Gable. “I’d like to get one shot of you at the finish of your swing.”

We went to the 10th tee, still carrying our glasses.

I took along Major Hardwicke, as technical adviser, figuring I might just as well have him work out the dough he had lifted from me. So the major sighted through the camera finder, okayed the top of Gable’s swing, and then exploded the flash bulb as the picture was taken. Gable, as a result of his coaching by Hillcrest professional, George Fazio, has one of the smoothest-looking swings of any Coast amateur.

“When they see that picture,” warned Hardwicke, “they’ll cut you down to a 5 handicap.” Gable grinned. “I’d love it. I’d rather play this game well than almost anything else I can think of.”

Throughout the afternoon, Gable had been extraordinarily cooperative, posing for any shots which Don suggested, even though we were playing a tight match. When we were alone, I commented about it.

“Hell, that’s not being nice,” said Clark. “The way I figure it, Ed, is that when somebody is assigned to a job, only a stinker would make it difficult for him to do it. On top of that, the pictures will do me good. Beyond all of that, Don is a former Air Corps guy.”

Gable chuckled. “You know, if you are nice to people, it’s amazing how much you can learn from them.”

I asked Gable if, as the public generally believed, he was a desperately lonely figure.

“I’d say definitely no,” he answered, after thinking it over. “For a time, I was at loose ends, but luckily, I never sold our house. So when I came back from war, that fact sort of gave me roots. The place had run down while I was away, and the work of fixing it up again occupied me, and then, as it started looking attractive, I got a terrific thrill of pride in it. Had I come back here and gone to live in a hotel, I am convinced now that it would have demoralized me.”

The conversation turned to pictures. I asked Gable what quality he looked for in a script such as Sidney Kingsley’s “Homecoming,” which he was making with Lana Turner for Mervyn LeRoy.

“All I want in a script,” he said, “is entertainment. If it will entertain people or amuse them, that’s for me. I am vitally concerned with the condition of the world and our country, but when I am acting, I won’t be a propagandist. People go to the theater to be entertained and to escape from their own problems. I only want to send them out feeling that they have spent a couple of enjoyable hours. Sometimes,” added Gable, ruefully, “your judgement of a script is sour. But that is one of the occupational hazards of the business.”

How long, I asked, had Gable been making pictures.

“I started out here in 1930,” he answered, “and I’ve been at it ever since. The first good part I ever had drifted to me quite by accident. The role had been offered to Edmund Lowe and a lot of other ranking heavies, and they all turned it down because it was to be a characterization of Al Capone, in Joan Crawford’s ‘Dance, Fools, Dance.’

“When I read the script, the ham in me responded to one scene in particular. As the gang chieftain, I dispatched my mobsters to wipe out a group of rival hoodlums. The script then outlined a wonderful scene. When my ‘hoods’ returned to report to me that they had machine-gunned not less than 10% of Chicago’s population, the camera revealed me sitting moodily at the keyboard of a piano, playing Beethoven!”

A gleam came to Gable’s eye: “I almost broke my leg getting to the telephone in the corner drugstore to tell the producer he didn’t have to look for another boy.”

Under Gable’s new contract, covering the next eight years, he’ll make three pictures every two years, or a total of 12 flickers. “By that time, 1955,” he grinned, “I’ll be ready for character parts, I guess. While I am not rich in any sense of the word, I am comfortably situated, and I guess by then, I’ll go traveling and fishing. Say, by that time I’ll be getting ready to play in the United States Seniors’ Golf Championship!”

During my month’s stay in Hollywood this past summer, I played a lot of golf with Clark Gable, and golf is an X-ray that shows up the most minute flaws in a person. Arrogance, cheating, temper, selfishness, ruthlessness, all come to the surface during the heat of a golf match, no matter how insignificant the financial stakes.

Gable and I played about 12 rounds together, stood on the same practice tee and went through the same exasperating experiences, played at different courses with different companions; so, just as he could give you a very accurate analysis of me, I got to know him.

Adolphe Menjou, one of our golfing pals in Hollywood, fears neither the Devil nor Daniel Webster. His frankness in exploding some of the legends of Hollywood curls the hair on your head. He is engaged in a 24-hour-a-day attack on smugness of any kind. I asked him once what sort of a person Rudolph Valentino had been. “Completely impossible,” said Menjou with his typical frankness. I am outlining this character sketch of Menjou so that you will appreciate the opinion he gave me of Clark Gable one day while we were playing at the California Country Club.

“Gable is the finest gentleman this industry has ever seen,” Menjou said. “I have known him for a good many years, and I have worked with him in many pictures, and there is no actor out here who even approaches his stature as a human being.”

Gable is not above “putting the horns” on you, though. In golf, this means that as your opponent putts, you extend the forefinger and the little finger of your hand to put a curse on him. Now and then it works. Gable tries it.

He showed up one day for a match, and at the first tee he told us: “Protect yourself in the clinches. Today, I am really ugly. I was so burned up at my bad shots yesterday that I didn’t get more than four hours’ sleep. Twice, during the night, I got up, took my driver and practiced my swing in my bedroom in front of the mirror, to find out what the hell I was doing wrong yesterday. Then I went back to bed, and two hours later I woke up again. I had suddenly dreamed out the solution to that bad hook. So for the next 20 minutes, I again practiced in front of the mirror. Brethren, you’d better be on your sticks today, because I haven’t had much sleep and I feel evil.”

Gable’s conscientiousness in golf indicates the capacity for concentration which lifted him to movie stardom. He is nobody’s chump and once he makes up his mind, he doesn’t yield easily.

Girls like him, naturally. When he is with them, Gable really turns on the charm. He is very boyish, despite his maturity, and the girls love the combination. He has two cars, a stunning Cadillac Convertible, royal blue in color, and a steel-gray Chrysler with a rigid top. He never puts the top up on the Cadillac and when he drives through Beverly Hills, the girls can be pardoned a double-take as they find him next to them in traffic.

“My God, it’s Gable,” exclaimed a startled femme, when I was with him one afternoon. Her car had come to a halt next to his at a stop sign, and I have never seen such a series of expressions race so quickly across a face. “H’ya hon,” smiled Gable, and she waved weakly back.

He got the rigid-topped car for longer trips as a safety precaution. In a convertible, he was barreling along at 70 miles an hour and suddenly, as he rounded a corner, an oil truck, its sides busted through in an accident, deluged the highway with gallons of the sticky, slippery black gold. Afraid to jam on his brakes, Gable’s car whipped into the oil-covered surface and went into a series of loops and spins. Fortunately, it didn’t turn over but from then on, he decided that on long trips he preferred the Chrysler.

Gable stull carries on correspondence with some of the men with whom he served in the Air Corps. His greatest friend was his Commanding Officer, Colonel Willie Hatcher. From what Gable tells me, Hatcher was a phenomenal person, both as an executive and as a warrior. That correspondence and friendship ended when the Army flier, not many months ago, was killed in the crash of his B-29 at Albuquerque, N.M. Gable still writes to the widow and two youngsters of his friend.

I would not be at all surprised if Gable, at some time, married again. I know he feels that a man living alone is a sort of a stray. I think he feels this keenly because all of his friends are married, and when he visits them, the fact of his aloneness is driven home to him. If he does remarry, I trust the girl measures up to him because, in my book, he is an exceptionally fine guy. The right kind of girl could do a great deal for him and I’m certain that Carole Lombard would be deeply grateful to her.