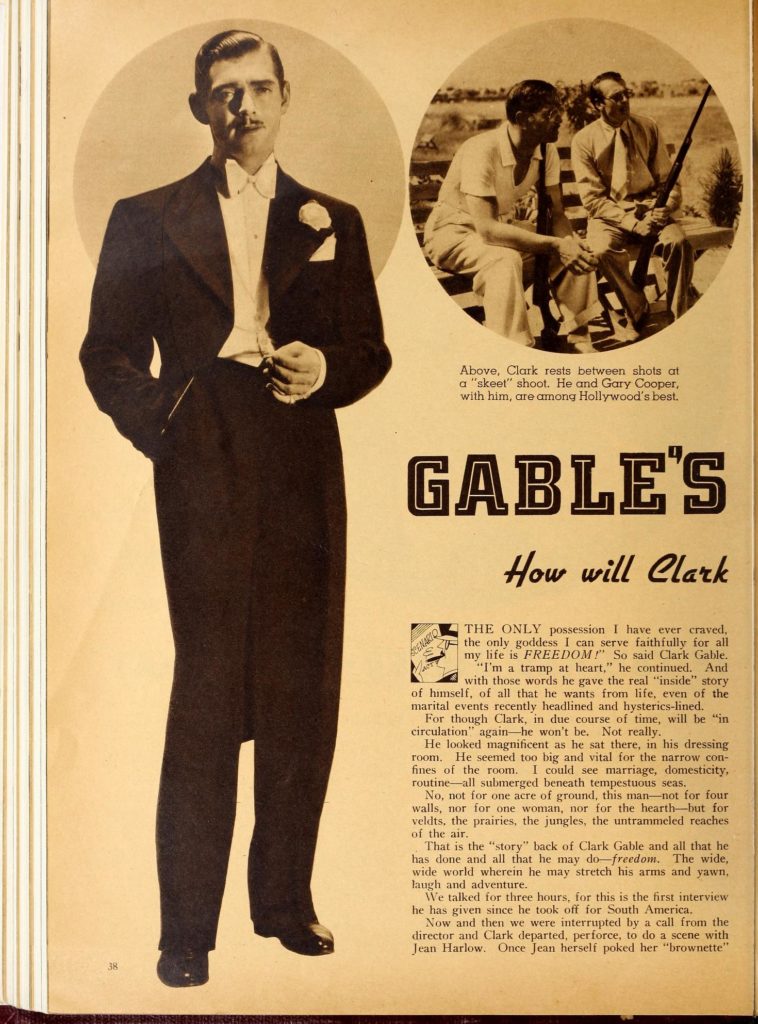

1936: Gable’s New Freedom

Gable’s New Freedom

By Gladys Hall

Modern Screen magazine, March 1936

How will Clark use it? Of course you know, he’s alone now

“The only possession I have ever craved, the only goddess I can serve faithfully for all my life is freedom!” So said Clark Gable. “I’m a tramp at heart,” he continued. And with these words he gave the real “inside” story of himself, of all that he wants from life, even of the marital events recently headlined and hysterics-lined.

For though Clark, in due course of time, will be “in circulation” again—he won’t be. Not really.

He looked magnificent as he sat there, in his dressing room. He seemed too big and vital for the narrow confines of the room. I could see marriage, domesticity, routine—all submerged beneath tempestuous seas.

No, not for one acre of ground, this man—not for four walls, nor for one woman, nor for the hearth—but for veldts, the prairies, the jungles, the untrammeled reaches of the air.

That is the “story” back of Clark Gable and all that he has done and all that he may do—freedom. The wide, wide world wherein he may stretch his arms and yawn, laugh and adventure.

We talked for three hours, for this is the first interview he has given since he took off for South America.

Now and then we were interrupted by a call from the director and Clark departed, perforce, to do a scene with Jean Harlow. Once Jean herself poked her “brownette” head in the door and summoned him. “Hi there, you!” she said—and “Hi, there, right back at you!” laughed Clark. They both caroled, “Love at first sight!”—and winked.

During Clark’s absences on the set, I combed my hair with the Gable comb, brushed my suit with the Gable clothes brush, renovated my face with the Gable powder puff—and emerged disappointingly unchanged.

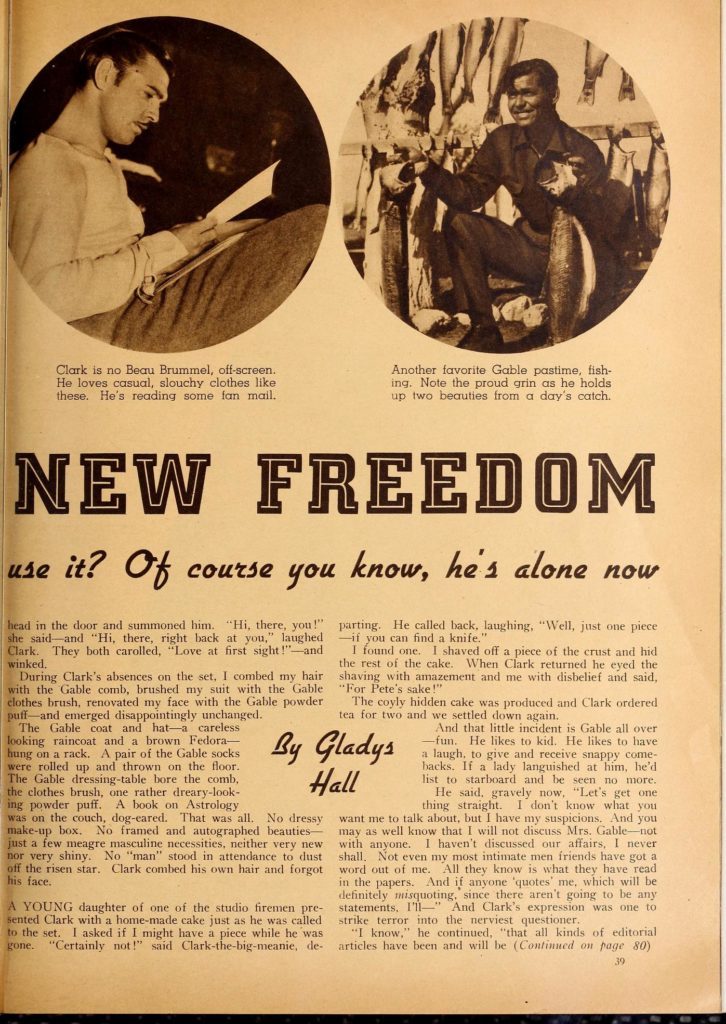

The Gable coat and hat—a careless looking raincoat and a brown Fedora—hung on a rack. A pair of the Gable socks were rolled up and thrown on the floor. The Gable dressing table bore the comb, the clothes brush, one rather dreary-looking powder puff. A book on Astrology was on the couch, dog-eared. That was all. No dressy make-up box. No framed and autographed beauties—just a few meagre masculine necessities, neither very new nor very shiny. No “man” stood in attendance to dust off the risen star. Clark combed his own hair and forgot his face.

A young daughter of one of the studio firemen presented Clark with a homemade cake just as he was called to the set. I asked if I might have a piece while he was gone. “Certainly not!” said Clark-the-big-meanie, departing. He called back, laughing, “Well, just one piece—if you can find a knife.”

I found one. I shaved off a piece of the crust and hid the rest of the cake. When Clark returned he eyed the shaving with amusement and me with disbelief and said, “For Pete’s sake!”

The coyly hidden cake was produced and Clark ordered tea for two and we settled down again.

And that little incident is Gable all over—fun. He liked to kid. He likes to have a laugh, to give and receive snappy comebacks. If a lady languished at him, he’d list to starboard and he seen no more.

He said, gravely now, “Let’s get one thing straight. I don’t know what you want me to talk about, but I have my suspicions. And you may as well know that I will not discuss Mrs. Gable—not with anyone. I haven’t discussed our affairs, I never shall. Not even my most intimate men friends have got a word out of me. All they know is what they have read in the papers. And if anyone ‘quotes’ me, which will be definitely misquoting since there aren’t going to be any statements, I’ll—” And Clark’s expression was one to strike terror into the nerviest questioner.

“I know,” he continued, “that all kinds of editorial articles have been and will be written. I can’t help that. I will not have authorized them. And I don’t care what they say as long as they don’t quote me saying it. My name will be linked, as it has been, ridiculously, with every feminine letter of the alphabet. I don’t give a hang for myself. I do hate to be a source of embarrassment, however unintentional, to any woman. And that’s that!”

“But your life from now on? Will you talk about that?”

“Why not?” said Clark. “My new freedom will consist in my living as I’ve always lived—only more so. I never did much partying about. Now I’ll do less. I haven’t been anywhere since my return from South America. I always have worked all day and gone home at night to read or play bridge. I always went hunting and fishing when I had time off. I always attended the races. I’ll do the same now—plus.

“I have a new clause in my contract which gives me six weeks of every year free for a trip. This year I went to South America. Next, I’ll go to China. The year after to India and then to Tibet, Greece, the Isle of Malta and to all the remote corners of the globe. I’ll always fly. That’s what I want and that’s what I have—now.

“And I’ll travel alone. Kipling says, doesn’t he, that ‘he travels fastest who travels alone?’ Well, he must have meant me, among others. Alone and by air. The combination should get me places.

“I don’t even want another man to go with me. Too apt to impose restrictions, and no matter how congenial you may be, there’s bound to be a conflict of opinions.

“I’m a lone wolf at heart and always have been. My mistakes have all come from disregarding this basic law of my nature. Now I shall observe it. That’s all.”

And I thought again, as he talked, sitting on the edge of a chair too fragile for him, No woman could hold this man. He isn’t a woman’s man at all. He’s too charged with a restless, reckless vitality, too untamed of spirit. He’s a gypsy. He has a huge impatience of shackles. He has no place—he simply doesn’t belong in night clubs, boudoirs, salons.

He doesn’t care for clothes. He never uses screen makeup—a powder puff is poison to him. He doesn’t want possessions. He wouldn’t know what to do with luxury. He scorns softness, small talk and coquetry. He laughs, uneasily, in the face of feminine adulation. He is like a bull in the china shop of marriage.

He was saying, “I’m living in a hotel in Beverly Hills. I like that, too. I don’t want a home. I have no sort of use for a place which binds me with taxes, upkeep and the fetters of possessions. At the hotel I can sleep and eat, come and go as I please and when I please. I can breakfast at five in the morning if I feel like it—and I often do—and no routine is disturbed. I can’t abide routine. It stifles me as physically as a pillow over my face.”

“So many things money can buy,” I suggested.

“What?” demanded Clark. “Huge estates, you mean, swimming pools, flocks of cars, interior decorators, parties—the things that belong to the luxury standard?

“But I have all those things and no strings to ‘em. The world is huge enough to do me for an estate. I can jump a tramp steamer any day without responsibility. I can swim in the seven seas which don’t have to be drained, scraped or sterilized. I can only wear one suit at a time, sleep in one bed, read one book and eat one mean.

“No, I wouldn’t know what to do with vast possessions. But they would know what to do with me. And here’s what: They would drive me mad in time. I want to move and keep moving. I want to inherit the earth, not ten fenced acres of it.”

“Is this all you want of life?” I ventured, thinking of all the richness at his very hand, the romance, the proffered hearts of the composite femininity of the world.

“What d’you mean, ‘all’?” Clark asked, his laugh resounding. “I’ve just told you I’ve got the earth and more. I’ve got my work, too. I like to work. I’ve done it for so long that it doesn’t hold any particular excitement for me, no novelty, but it keeps me moving, gives me an interest. And now, between times, I can go where I please. What more is there to want?”

“Well,” I said, fascinated by the vision of the thousands of women who have mobbed him for his autograph, a word, a smile, a nod—“well, I mean women. Don’t you ever think it might be fun to adventure amorously—just a dash of Casanova, y’know?”

“Gosh, no!” laughed Clark. “I like women, of course. I like companionable women with a sense of humor, women who can laugh with a fellow. I don’t know what to do with strange ones who look at me all goggle-eyed. They make me feel uncomfortable. They always have. It’s not going to be any different now. My new freedom is the freedom of the seas—and no sirens on the rocks, either.

“Besides, it’s a hot of hooey—women being ‘crazy’ about a star—whether it’s me or the next one. They can’t care about me because they don’t know the real me, the man behind the star. It doesn’t make sense. Every time I appear in public I imagine people are saying ‘Oh, so that’s Gable, is it?’ (which is ridiculous, for Clark is handsomer off the screen than he is on—and “regular.”)

“Look,” said Clark, in the tone of voice one uses to each a very dumb child a simple lesson, “the day I was leaving South America a crowd came to the airport. How they knew I was leaving, I’ll never know. They are more rabid fans down there than they are up here, if possible. I kept as much to myself as I could and as I was waiting to take off, I found myself standing next to a nice-looking girl of about twenty. She looked sensible and she was staring at me. I said to her, on an impulse, ‘Look here, what made you come down here to see me?’ And she answered, ‘Curiosity.’ She spoke the truth and I liked her for her honesty. Curiosity—that’s the answer. But I’m not a curiosity. I’m just a man like any other and all I ask is to live my life in comfort and freedom.”

I recalled the very first interview I ever did with Clark. It was right after MGM realized what manner of star they had “in the bag.” I remember saying, “How will you feel if at the end of the year you find yourself in the spot Valentino once occupied—when women literally tear the clothes off your back?” And Clark answered, an honestly naïve horror in his fine eyes, “I think it would be sorta repulsive.” Well, he still thinks so.

“When you’re in Hollywood and working, what do you do evenings?”

“I usually go home to the hotel, lock the door, go to bed and read.”

I said briefly but with feeling, “Pig!”

“Pig?” inquired Clark politely.

“Pig,” I reiterated firmly— “with all the romance in the world, just waiting ‘round the corner, with all the eager-eyed girls, all the amorous adventures, and you shut yourself up in your room to read!”

“I can’t seem to make you understand,” said Clark, in the loud, rather labored tones in which one speaks to the slightly deaf, “that’s just what I want to do! And that’s what freedom is for!”

Clark laughed. Hus hands made a gesture dispensing with the world, the flesh, the devil and all the angels.

I said, “Is it out of turn to ask whether you think you will ever marry again?”

“Nope, not out of turn. But I don’t know. I can’t say that I won’t. I may, but it’s a but soon. I’m not ummarried yet—and I never look ahead. Some day, no doubt, I shall have encompassed the earth, since there are limitations even there. And when that day comes, and after the screen has hung a ‘To Let’ sign on my dressing room door, I may buy a ranch out here in California and settle down—some.

“But first,” said Clark, stretching out his arms, that lazy smile curving his mouth, “there are the seas to be sailed, the skies to be explored, the lakes to be fished and the mountains to be scaled. There’s freedom—and it’s mine!”