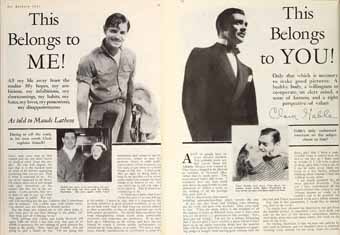

1935: This Belongs to Me! This Belongs to You!

As told to Maude Lathem

Screenland, January 1935

Gable’s only authorized interview on the subject closest to him!

Daring to tell the truth, in his own words Clark explains himself!

A lot of people have always refused stardom. You probably know neither Lewis Stone nor Adolphe Menjou ever wanted it. They always begged to be allowed to continue in featured roles, rather than be made stars. This once seemed rather silly to me. I wondered how many man could turn down an opportunity to earn thousands of dollars a week, to say nothing of all the prestige that goes with it.

But it’s the prestige that causes irritating misunderstandings which involve the star.

It was this that Stone and Menjou were refusing, not the work that goes with stardom. They were equal to that. When the other fellow is the recipient of all the honors, it looks so different from what it does when you are the proud (?) possessor of this prestige. Now, don’t get me wrong! I’m not for a minute intimating that I am not glad I have reached a place where I don’t have to sit up nights worrying about how the monthly bills will be paid; glad that I am not conscious of gnawing pangs of hunger from having gone without food for days; glad that I have a comfortable home to return to at the end of the day, so I don’t need to wonder if I will have a place to sleep; glad that I own a car, so I can be miles away from my work in a few hours, without thinking about whether I feel like walking twenty miles.

I am deeply grateful for all these physical comforts. You see, I have experienced all the inconvenience that comes to one without income or work, so I couldn’t fail to be grateful for the fact that I have permanent work and a steady income.

But, just in this connection, I would like to remind you that we do work!

No matter how pleasant the impression you get from the finished picture, it represents work, hard work, not only on the part of the director, cameraman, author, electrician, prop man and many others, but work on the part of the actor.

My feeling, therefore, is that we earn our salaries by our work in pictures, and we shouldn’t have to continue working every minute we are away from the studio. Don’t raise your eyes at that remark and say you didn’t know we worked away from the studio! No one will dispute the fact that it is the hardest kind of work to be forever appearing something that you are not. That is what is expected of us. We are never supposed to let down. Of course, there are a few people who play themselves on the screen; but they are in the minority. Lucky persons, they never have to put on any act when they appear in public. For myself, I’m anything but the gay Lothario that I sometimes play in pictures. I’m a plain man, with simple tastes, who doesn’t care for clothes or formal parties.

But the thing you wanted me to talk about today is just what part of our lives belongs to the public, eh? And what part of it belongs to us?

Well, perhaps only Garbo and Leslie Howard will agree with me when I say that only that part of us which is necessary for the making of good pictures belongs to the public. Now, don’t get excited. I’m not going to pull a Garbo on you. I’m not going into retirement and refuse to see interviewers, refuse to pose for pictures, refuse to answer my fan mail, or any other of a dozen things of this sort. I shall probably go right on doing them as long as my position on the screen seems important enough for these things to be desired of me. But you asked me to tell you what I think about it. This is what I am attempting to do.

To elaborate a little what I said about that part of us which belongs to the public: I mean by that, that it is imperative that we keep ourselves in good physical condition, so we can do our best work; that we shall keep our mental outlook as clear as possible, so that we shall approach our work with proper perspective. We should keep ourselves free from entanglements which would cause unfavorable comments and embarrass our producers. If we have built up a following on the screen, and have led our friends to expect a certain quality performance, we should not let them down, as it were. We owe a courteous, friendly consideration to the press who have publicized our good points and minimized our bad ones. We owe the finest possible co-operation to our producers who have given us such wonderful opportunities. But I do want to feel I can live my life like any other individual when I am between pictures!

If I choose to don my old clothes and fish and hunt, miles from civilization, I hate to think my friends are feeling that I should have remained in Hollywood and danced at the Cocoanut Grove or the Trocadero every evening and lunched at the Brown Derby every noon. I like these places tremendously, but getting back to nature means more to me than almost anything. And I love studying people too; people whom I do not know at all, who may live in an entirely different manner from the way I live. Because of this wanting to study people, I am just as likely to park my car in a remote district and walk for miles, stopping ay any home I pass and asking for a meal, just as any vagabond would do. Does that sound terrible to you?

To begin with, I have never recovered from my astonishment at the interest people from all over the world have in professional people. This is not just true of America. It is true in almost every country of the globe.

Undoubtedly, if the public never read anything about us, from the time we finished one picture until another was ready for release, they might not be so eager to see the new picture; so we should be, and I am, grateful that they write to know about our soap, our stationary, our books; but in the face of all this, I do want to live my life just as Tom Jones or Bill Smith in Oshkosh might do. Unless I do something that is so flagrantly immoral that decent people are offended, I don’t think my personal habits concern anyone but me.

Now, don’t misunderstand me! I haven’t the slightest idea of doing anything that could make the public ashamed of me; but what I am trying to get over to you is that I conduct myself in the manner I do, not because some public demands or expects it of me, but because I choose to do so myself. If this were not true, I think it might weaken one’s moral fiber. If such a thought governed me, when the time comes that I no longer mean anything to the public—and such time comes to all professional people—then I might feel, “Oh, to blanket blank with it all, now I can do as I choose.” And it is possible it might appear to me at that moment that freedom might mean breaking all the laws of rhyme and reason. No, so far as possible I mean to live my own life now. I hope it pleases anyone who is interested, but I must continue to cultivate the habit of self-respect, no matter what anybody thinks about it.

Self-respect means that I am honest with myself. I am not acting when I am not before the camera. The work I am paid for, and I will play any part I am called upon to play, if it is within my ability. When I am through, I want to drop into any mood I desire. If I feel like swearing, I shall probably swear. I don’t often have the impulse, but it is an outlet at times. If I want to go to the skating rink with my boy or somebody else’s boy and act like I am fourteen, I think that is my privilege. There are times when I don’t feel more than fourteen. On the other hand, if I feel about ninety, and sit in moody silence, I think I merit that privilege, no less than the man at the service station who does and says what he pleases when his work is over.

For the moment, I am not considering the times that we make public appearances and expect to receive attention. Does that sound conceited? I don’t mean it that way. I mean when we are urged to make personal appearances, we hope, down in our hearts, that we are important enough to the public that a fuss will be made over us. If this doesn’t happen, it means our drawing power has diminished and producers may value us accordingly so don’t let anybody fool you when they say they do not like this attention. We are not stupid enough not to want it, no matter how embarrassing or inconvenient it may be.

I won’t speak of my own personal appearances, but I am reminded right now of the recent trip of Dick Powell, when he appeared at the larger theatres in the East. So eager were the crowds to get some souvenir, that they almost left him unclothed. He started out with six dollar handkerchiefs in his coat pocket, but as they were removed one after the other, he rushed to a store after the next performance and bought himself several hundred cheap handkerchiefs. Of course, we can imagine that he was furious, and yet I have an idea that he couldn’t help enjoying the fact that the women were so crazy about him. We are every one just human after all, and all share the same emotions.

I do resent having every writer I meet question me about how many women I have loved. A bank president is not any better banker, nor any worse, for having been engaged three times or for never having been engaged. Why should it mean more in an actor’s life? Any man who reaches maturity and has never imagined himself in love is a funny sort of man. On the other hand, a man of any age who boasts of his conquests is about as despicable a human being as can be found.

If I refuse to discuss any part of my past, and later someone discovers that I once went to Sunday School with Lucy Cotton or Mary Jones, they say: “Oh, he’s ashamed of his past.” Now, I am not ashamed of anything I ever did, but I am not going to make an ass of myself by boring people with reading it. If we say that women will always interest us, they feel we are fickle and undependable. If we say we love our wife and all other attachments are of the past and completely forgotten, they feel we are a little selfish and they look around for some other player who admits he can love a dozen women at once. You see, we have our Scylla and Charybdis, too, and we are caught if we do or if we don’t.

But seriously, I do not think my past is any concern of the public. If there were anything in it that indicates obstacles overcome, the knowledge of which would be an inspiration to some one else, then I think it should be told, but it should be told for that reason only.

One of the things that I am particular about is telling the truth. I was taught it from my youth. My father always said anyone who would lie would steal. Now, when I am asked a lot of personal questions, I feel if I answer them at all, I must answer them truthfully. If I don’t answer, they get the information elsewhere and it looks so little like the facts that it makes me feel I will answer all next time—no matter whom I offend. The space is so limited, a writer never explains all we say and invariably we are misunderstood. So, I still prefer the method of Maude Adams. Her public liked the illusion and wanted to remember her only in the parts she played. I would like to do some really great characterizations and be remembered by those, rather than the color of sox I wear. Do you think I can?