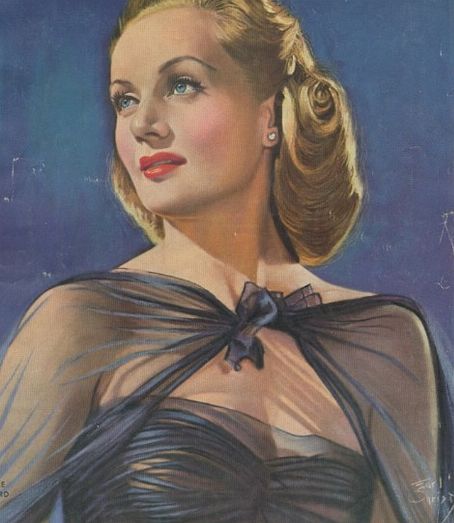

Remembering Carole Lombard

Carole Lombard Gable died 72 years ago today, in a horrific plane crash. She was 33 years old. It’s always difficult to realize that she died such a long time ago, as she always comes across as so modern.

This memorial article from Hollywood magazine sums her up quite nicely. Rather than being sappy about her death, it is rather a tribute to the person that she was.

“This Was Carole,” Hollywood magazine, April 1942:

Carole Lombard was a great woman.

The president of the United States paid tribute to her and the service she gave her country in time of need. International press associations wrote in praise of her and named her a martyr of the war. Leaders of the film industry eulogized her as a woman and deeply mourned the passing of a fine artist.

But this, too, was Carole Lombard in the hearts of the little people she loved, the men and women with whom she lived, laughed and worked.

Five years ago a secretary in one of the departments at Paramount became ill. Long before her meager savings ran so low as to fret her, Carole quietly paid the rent, sent unexpected little gifts of money, brought her clothes, nonsensical gag presents, and small luxuries. Then an eye injury developed and it was feared the girl was going blind.

Immediately Carole consulted her own doctor about possible treatement and personally checked with Washington for the latest equiptment devised for the entertainment and education of the blind. And always, throughout long weeks, she snatched time every few days for a cheery telephone call.

“Don’t worry,” she would say. “Together we can lick this thing.”

Together they did.

The Lombard generousity was legendary but always it was tempered with widowm and an instinctive sense of the real need of the moment. Throughout the seven years of her association and friendship for her stand-in, Betty Hall, Carole gave her many gifts to add to the beauty of her home. Nor were they second-best in quality. Frequently the articles were duplicates of things to be found in the Gable-Lombard household.

Last Christmas, Betty was in bed, recovering from burns received in a serious accident. In lieu of the living room chair orginally planned, Carole sent a great box containing lovely perfumes, a luxuriously soft bedjacket, frilly nightgowns, down pillows and a fluffy thick blanket. “The least you can do,” said a gay little note, “is get well in style.”

The frantic efforst made to keep the news of Russ Columbo’s death from his blind and ailing mother were well known. Few know, however, of the part Carole played in the masquerade.

To account for her son’s prolonged absence, Mrs. Columbo was told he was in London, making a moving picture with Carole. In the course of her romance with Russ, Carole naturally had grown close to mrs. Columbo. Thus, to keep the heartbreaking news from her, Carole wrote weekly letters, fully of gay chit-chat and news of their activities, which were supposedly postmarked London and read to the blind mother.

It was not a dictatorial whim which made Carole insist upon a clause in her contract giving her the right to choose the personnel of the crews on her pictures. She made the stipulation in order to protect the men and women with whom she had worked for years and for whom she felt great loyalty. The clause was never invoked, but it proved an effective club in behalf of their interests.

To Carole, a promise was a promise. At the close of one picture she had promised her mother, to whom she was devoted and in whose appearance she took enormous pride, to go shopping with her for new clothes. The final morning of shooting prooved unexpectedly tough, with Carole working in mud and water for several hours. On top of that she was to join in the cast and crew party to celebrate the finish of the picture. That ate up two more hours of her time and energy.

Nevertheless, rather than disappoint Mrs. Peters and break the promise, Carole cheerfully set out upon the shopping expedition and enthusiastically helped in the selection of all items. Mrs. Peters demurred at the extra efforst when her daughter was so tired.

“Nonsense!” said Carole. “It’s worth it just to see you look so beautiful!”

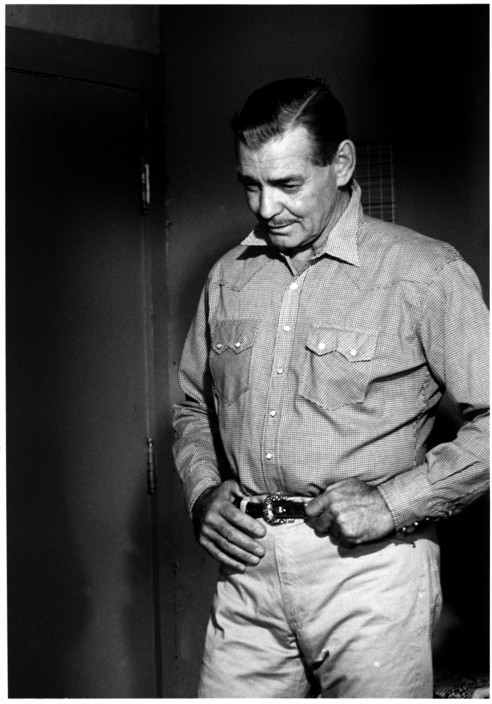

A good business head sat squarely atop the Lombard shoulders. On a recent pheasant hunting trip to the Dakotas, Carole, Gable and the two friends who accompanies them encountered a delay in return when their plane was grounded by bad weather.

Carole’s suggestion was adopted. Buy a car, drive home, sell the car. The entire return trip, including transportation, meals and hotel lodgings, cost only $150 for four people–less than one-half the one-way fare by air.

In the same fashion she was intolerant of waste. In redecorating her house, for example, old items of value were not discarded. Drapes, being replaced by new fabrics and colors, were utlized in upholstering furniture, or were recut and dyed to fit other rooms. Despite her wealth, waste not, want not, was a daily motto.

One day Gable came to the lunch table direct from working in the fields at their ranch home. Carole spied his dirty hands which he was trying to hide, little boy fashion, under the table.

“March, young man!” she said, pulling him by the ear and pointing to the lavatory.

Gable marched, meek as pie. When he returned, Carole had nibbled all the choise tidbits off the top of his salad.

Production on a costly picture was held up one day when it was found a minor executive had failed to carry out orders through sheer negligence. Angrily Carole telephoned and gave him what-for. Then she telephoned the studio boss.

“Don’t hang the rap on X for this trouble,” she said. “It’s all my fault. I forgot my appointment with him and there was nothing he could do.”

The friendship of Carole and Fieldsie, her former secretary, dated from the days of Mack Sennett comedies when Carole was the bathing beauty and Fieldsie the fat girl who stopped the pies. When Fieldsie first began to serve as her secretary, she flatly refused to accept money from Carole because she could not type or take dictation. Carole solved the problem in her own way. Afte rbuying the necessary materials, she would hire a dressmaker, kidnap Fieldsie, and refuse to allow her to leave until a new wardrobe had been completed for the stubborn girl.

Shortly before the tragic accident, Loretta Francelle, the hairdresser who had served her for 13 years, was talking with Carole. Carole was tired and showed it.

“You don’t have to make pictures, Carole,” Loretta said. “Why don’t you quit working, enjoy life, and maybe have a family?”

“I know, Bucket,” Carole said. (Bucket was her personal nickname for Loretta.) “But I have my little people to take care of, and I don’t want to put that burden on Pappy (Gable). He has his little people too.”

The day Carole left Hollywood for Indianapolis, Bucket dressed her hair. They fell to talking about old times, the people each had tried to help, and the lack of gratitude which sometimes was evidenced. Bucket in particular was upset about a recent example of a good deed which had boomeranged in her face.

“I’m going to stop being a sucker!” she stormed. “Hereafter I’m going to look out after me and me alone!”

Carole smiled wearily. “Listen, Bucket,” she said. “You’ll end your life doing for the other fellow, and I will too.”

4 Comments

Tonya

Very Sweetly written

Kendahl

I know they made up a lot of stuff for movie magazines in those days, but these have a ring of truth. They definitely speak to her spirit. Really nice post.

Peter Trinidad

I was not born until 1960 but looking at her movies and reading about her, this was definitely a very classy and strong woman. Wish there were more of her nowadays. Besides being a great actress, she was a great human being first of all.

We miss you Carole.

Peggy Hill

Dear Mrs Gable

Godspeed to You,Russ & Clark

I so admire you.