1937: The Utterly Balmy Home Life of Carole Lombard

By Harry Lang

Motion Picture, February 1937

Listen! Wanna step into the merriest, maddest home in Hollywood? Then get a look-see at Lombard’s. It’ll sure slay you!

Take—if you can stand it! Carole Lombard’s household—

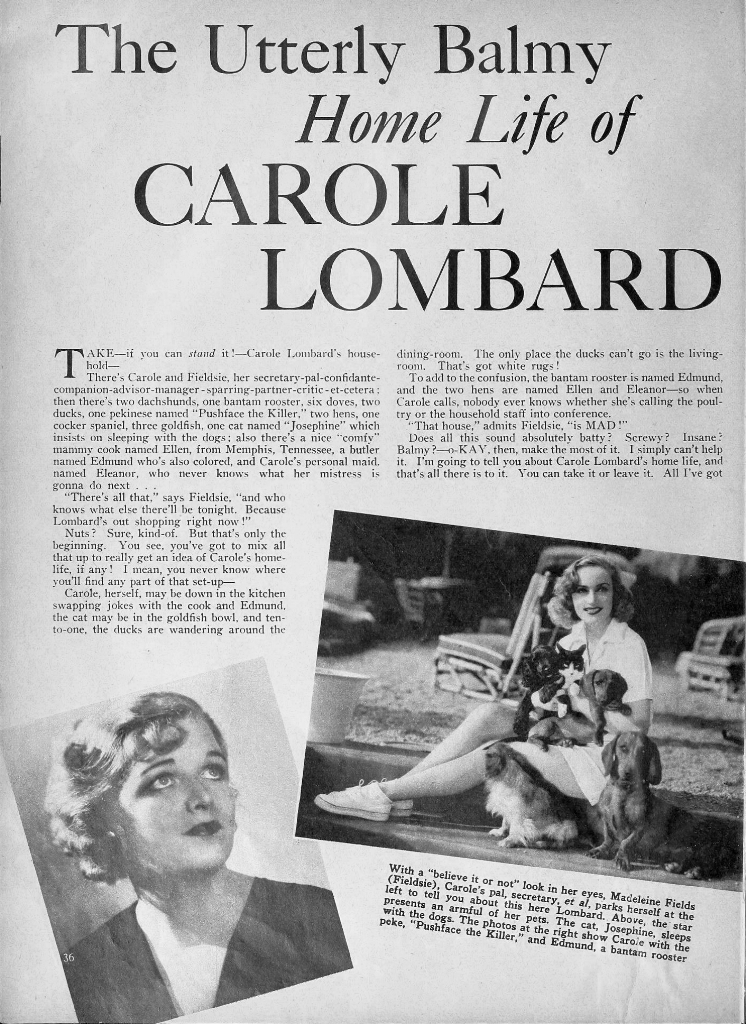

There’s Carole and Fieldsie, her secretary-pal-confidante-companion-advisor-manager-sparring-partner-critic-et-cetera; then there’s two dachshunds, one bantam rooster, six doves, two ducks, one Pekinese named “Pushface the Killer,” two hens, one cocker spaniel, three goldfish, one cat named “Josephine,” which insists on sleeping with the dogs; also there’s a nice “comfy” mammy cook named Ellen, from Memphis, Tennessee, a butler named Edmund who’s also colored, and Carole’s personal maid named Eleanor, who never knows what her mistress is gonna do next…

“There’s all that,” says Fieldsie, and who knows what else there’ll be tonight. Because Lombard’s out shopping right now!”

Nuts? Sure, kind of. But that’s only the beginning. You see, you’ve got to mix all that up to really get an idea of Carole’s homelife, if any! I mean, you never know where you’ll find any part of that set-up…

Carole, herself, may be down in the kitchen swapping jokes with the cook and Edmund, the cat may be in the goldfish bowl, and ten-to-one, the ducks are wandering around the dining-room. The only place the ducks can’t go is the living room. That’s got white rugs!

To add to the confusion, the bantam rooster is named Edmund, and the two hens are named Ellen and Eleanor—so when Carole calls, nobody ever knows whether she’s calling the pultry or the household staff into conference.

“That house,” admits Fieldsie, “is MAD!”

Does all this sound absolutely batty? Screwy? Insane? Balmy?—OKAY, then, make the most of it. I simply can’t help it. I’m going to tell you about Carole Lombard’s home life, and that’s all there is to it. You can take it or leave it. All I’ve got to say is this—when it comes to the business of getting the most downright, sheer fun out of this usually drab business of living, then I had all prizes unreservedly to Carole Lombard.

There’s the telephone at her house. It’s all right when Carole’s working and at the studio and can’t answer it, herself. But when she’s home, it’s heaven-help-the-caller-uppers! Carole always answers, unless somebody a little more calm can beat her to it. And when Carole answers, you never know what’s going to come of it.

“’Alloa—yah, ‘alloa—hoo iss diss?” she’ll scream into the phone. The bewildered somebody-or-other at the other end’ll ask for Miss Lombard, please.

“Mees Lombard—ah, zen, she iss not at home, yah!” Lombard will reply, mixing any and all dialects.

“When will she be?” the indefatigable caller-up may persist.

“Ay do not knowing, sank you pleass. Ay t’ank ay go home now.”Carole is liable as not to reply.

“Say, who is this talking, anyway?” the phoner may inquire, if he’s wise enough to know Carole’s tricks and suspects it’s Carole, herself. Then Carole gives way. She just goes into hysterics. “Oh,” she screams; “oh, oh, oh—you go jump in a lake, honey—and come on over, I’m giving a little dinner tonight.”

That’s the way it goes. “I wonder what kind of a crew people think we’ve got here,” wonders Fieldsie, “when Carole answers the phone—she may be a Jap, or a Swede, or a Filipino, or a Russian, or a Chinaman as the mood takes her. I tell you, Lombard on the phone just drives you crazy!”

And there’s the bee-bee gun. It was a gag present to Carole from—well, anyway, there’s the bee-bee gun. Carole takes it out in the backyard and shoots it. She’s got a target on some bushes, but she’d rather shoot anything and anybody else.

“I don’t dare go out in that yard,” says Fieldsie, “when Carole’s got the bee-bee gun, without wearing a red hat. With that gun, Carole is just too bad–!”

It isn’t only the gun that takes Lombard into the yard. She gardens, too. Oh, yes—she’s got orange trees and lemon trees and she picks the fruit and works in the garden. She always dresses for it, though—overalls, white cotton gloves, and a sunbonnet-sue top-piece. Lombard “dresses the best gardener I ever saw,” says Fieldsie. That’s another thing about Carole that just kills Fieldsie—“no matter what she does, she always dresses the part!”

But about those animals I mentioned.

You wanted to know more about ‘em, didn’t you? Well I meant it when I said you’ll like-as-not find the ducks in the dining room. They were baby ducks when the gang at the studio gave them to her, but they’re growing up now. They have the run of the house, except nights. Then they’re locked out. But in the morning, Lombard has to go out and say good-morning to them—or, if she doesn’t feel like going out, then they’re let in to say good-morning to her. The rooster and the hens were given her by her servants, as a gag, too. That’s the kind of grand household this is—even the servants can play gags on Lombard. But Lombard’s going to have to get rid of the rooster. Because not long after she got him, an agent for the Bel-Air subdivision, where Carole’s house is, came and explained that the neighbors liked Carole and all that, but roosters crow, “and in your contract there’s a clause about no poultry, so you know, we can put you out…” So Carole’s going to give the rooster away, because she’s having too much fun living there.

The dogs? Oh, they’re assorted gifts. “Fritz,” one of the dachsies, was just about hi-jacked, though, by Carole. It belonged to Mr. Whoozis—a friend of Carole’s—who was going away on a hunting trip or something. He loves to hunt.

“Why don’t you leave Fritz here?” Carole suggested.

“No,” said Whoozis.

“Why?”

“Because I know you’d never give him back to me.”

“Hmph!”

So Whoozis went away, and left Fritz with his own servants. Now it so happens that his servants are the mother and father of Carole’s maid. And ma and pa came to visit. And they brought Fritz along. “Why don’t you just leave him here? You might just as well,” suggested Carole to them. They did. And so Whoozis came back from the hunting trip, and there was Fritz in Carole’s house. Fritz didn’t seem particularly excited when his master returned.

“See?” crowed Lombard; “you’ve been gone three months and now he doesn’t even know you!” So Whoozis gave up, and now Fritz belongs to Carole.

“Pushface the Killer” came because Carole hates Pekes. A friend asked her one day: “You like dogs, don’t you?” (This was before Pushface’s advent, and led to it.)

“I just L-O-V-E dogs,” Carole cried.

“Pekes, too?” asked the man.

“I H-A-A-A-T-E Pekes!” howled Lombard.

That settled it. Because Lombard plays positively outrageous practical jokes on everybody she knows, everybody she knows plays outrageous practical jokes on her. So next Saturday, a big basket of flowers arrived for Carole from them man who talked about the dogs.

“Ooooo,” cried Carole, delighted, and buried her face in the flowers.

“Yap! Yap! Yap!” went the flowers, and something nipped Carole’s nose. “Those,” she protested, as she dropped them, “are the utterly weirdest flowers I ever saw. They bark and bite.”

Investigation revealed, buried deep in the posies, the Peke pup, six inches long, but full of vinegar! Carole’s hatred for Pekes ceased instantly, and now that she’s found the ideal name for him, “Pushface the Killer,” he’s lord of the household.

Josephine, the cat, just was there when Carole moved into the house, and wouldn’t move away. So Carole can’t do anything about it, and neither can the dogs. Josephine just lives with them, the shameless creature. The cocker spaniel is another birthday gift from Carole’s friend. The goldfish—oh, Carole bought them herself, one day. She doesn’t know why, yet. And nobody seems to remember when, where or how Carole got the six doves.

Of routine, there’s no semblance in the Lombard asylum. Except when she’s working. I mean, don’t get from this story an idea that Carole’s “tetched in the haid”—anyway, not much. Honestly, when she’s in work, during a picture, she lives a hard and strict routine. Hardly any play, no parties, just work, study, eat and sleep. But between pictures, I mean—

Well, she’ll get up at any hour at all, and begin telephoning. She’ll telephone people at 8 am, and make them like it! That’s an index to Carole’s real personality—when people don’t get mad when they’re called up at 8 am, then the caller-upper must be swell. She is. She’ll call up her mother. Then she’ll call up Mrs. So-and-So.

And so it goes on. By the time an hour of phoning is done, Carole has personal-and-social-secretaried all her friends, she is up and about with a glow of boy-scoutish good-deeds-done-for-the-day pride. Then heaven help Fieldsie…!

Fieldsie may be hard at work on the Lombard books. In busts Lombard:

“Hey, Fieldsie, you old bookworm; I feel like talking!”

“I don’t. Beat it,” commands Fieldsie.

Carole sits down. “Look at poor ol’ Fieldsie, slaving away at those nasty ol’ books” she begins. “Poor ol’ Fieldsie—gotta work, while I can play and have fun. Whee!”

Fieldsie stands it as long as he can. Then she gets up and goes to work on Carole. Fieldsie outweighs Carole. When Fieldsie gets up, it’s Carole’s cue to flee. She does, and Fieldsie goes back to work—if she can. “She just drives me mad!” says Fieldsie.

Then Carole makes the rounds, saying good morning to Ellen, the cat and dogs, Eleanor, the ducks, the chickens, Edmund, the doves, the goldfish and whatever else is around. Then she decides to give a party that night.

Now, parties are something with which the Lombard reputation is inseparably linked. But get this strange truth—Lombard, for all the party-reputation she has, gives and goes to fewer parties than most other stars in Hollywood! In the last few years, she hasn’t been to the nite-clubs more than a half-dozen times; three or four parties a year is all she goes to. But she does like to give them—and yet, not as many or as big ones as you’d imagine. A half dozen guests is her idea of fun, rather than a 200-guest brawl. What gives Lombard a party-name is that her parties are different, always.

“She can’t stand the idea of just giving another party,” explains Fieldsie. “It’s got to be different. She couldn’t give an ordinary party if she wanted to!”

And you never can tell what idea is going to hit her. The night after she got the chickens, she gave a party. The chickens gave her an idea. “We’ll make it a barnyard party,” she decided. So she spread some straw and hay around the place, let the chickens in, put some hard-boiled eggs here and there, spread red-and-white-checked table cloths around, hung a few barnyard lanterns over the dining-room lights, and wham—the next day the columns reported Carole’s Great Barnyard Party.

In the line of food, she’s a wow. She knows her foods, orders them herself, and always has something grand, something new, something odd. The other night, when the dessert-course rolled around, the guests fell into heaps of shrieking laughter when Edmund, not a smile on his perfect serving face, came in with handfuls of ice cream cones for dessert!

“Ice cream cones! Imagine!” says Fieldsie; “that Lombard….!!!”

Funny—but Lombard can cook! Maybe it’s the last thing in the world you’d expect a gal like Lombard to do, but she does it magnificently.

But she can’t even sew a button on!

The servants are heroes. They never know when dinner’s going to be, for example. It might be 6, or it might be 11:30pm—just as the mood and opportunity strikes Carole. And there may be two or twelve people in. Always, the staff is ready. And they love it. That, too, is a tribute to the Lombard personality—I don’t think that anywhere else in the world will you find a mistress of a household who could keep a staff of servants on an utterly mad schedule like that. Yet Carole does—and Ellen and Eleanor and Edmund love her. Carole loves them, too. They’re not just servants to her—they’re human beings, with problems and happinesses that dig into Lombard’s heart. You’ll find Carole down in the kitchen laughing with the servants and sympathizing with their personal woes, when the need be…

But that’s characteristic of her. There’s just one thing in that world that can get Lombard “down”—that’s somebody else’s grief. She has the biggest heart in Hollywood, even though she does try to hide it under a screen of hard-boiled worldliness. Her own troubles rarely bother her, much. But let some friend—even some chance acquaintance—suffer grief or trouble, and if Carole hears about it, down she plunges into the depths of sympathetic sorrow. She’ll torture her mind to help the other person devise a way out of grief. She’ll do all she can materially—and everything she can, spiritually. Hospital visits take up much of her time. She sends flowers, gifts, necessities to where they’re needed, always. And it’s not an act—it’s real. She can crowd more of other people’s troubles into her heart than you’d ever believe.

Greatest delight at home to Lombard is—here’s a new slant on the gal!—the radio.

“Sundays, from two in the afternoon until bedtime, is just nobody’s business,” says Fieldsie. “that’s when all the big-time radio programs are on, Magic Key, Stoopnagel and Budd, Joe Penner, Bob Ripley, Jack Benny, Eddie Cantor—all of them are on, you know…”

When she has time between radio and animals and the telephone and sending flowers and gifts to people and plotting dinners and parties, Carole usually’s thinking up a gag to play on somebody. Like plastering an actor’s dressing room with cards, on the night he was to play George Washington over the radio, reading, “Now the Great Lover becomes the Father of his Country!” Or giving him a decrepit Ford for a Valentine present. Right now, she’s seriously considering buying an old fire engine that’s for sale on a Hollywood used car lot and sending it to him.

Or maybe she’s thinking up some new way to break in on Fieldsie when Fieldsie has work to do.

“She just kills me!” says Fieldsie, who really loves Lombard more than her own life. “But honest, sometimes I could kill her!” Fieldsie concludes. But you know she doesn’t mean it.

One Comment

Gary Jones

Wonder if anyone knows the Cocker Spaniels name.