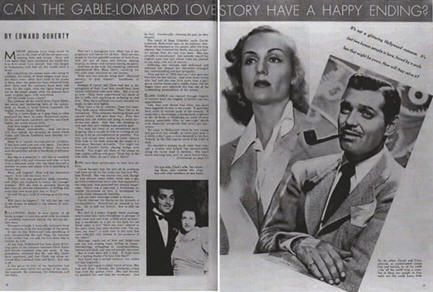

1938: Can the Gable-Lombard Love Story Have a Happy Ending?

By Edward Doherty

Photoplay, May 1938

Motion pictures have done much to prove the truth of all the old saws concerning love and lovers. Over and over again they have convinced the world that true love never runs smooth, that love laughs at locksmiths, and that all the world loves a lover.

But sometimes the screen stars who bring to attention the verity of these adages must wonder about them—after their work in the studio is done, after the paint has been removed from their faces and the costumes have been laid away for the night, after the lights have gone out on soundstages, after the players have come to grips again with actualities.

All the world loves a lover?

Yes, perhaps all the world loves Clark Gable, the suave and fascinating hero of the screen. And, no doubt, it loves Carole Lombard, the impish, kinetic, funny darling.

That is, loves them as it sees them in roles produced for them by some Hollywood writer. Of the real Carole Lombard, and the real Clark Gable, the world knows little.

And love laughs at locksmiths?

Many times, undoubtedly. And yet—how will love unlock the situation in which Clark Gable and Carole Lombard have become imprisoned?

Here is a typical moving-picture situation. It has been used over and over again. You have seen it developed hundreds of times. You have seen the problem solved in hundreds of different ways.

But this is a situation in real life—a beautiful blonde girl, witty and winsome and wise, in love with a debonair actor who has been married a number of years and whose wife is unwilling to divorce him.

What will happen? How will the characters react? How will the story end?

Will the wife step gracefully aside, someday, and allow her husband to marry the younger woman? Will she wait in patience, knowing that time oft withers infatuation, or feeling that even true love must give way to duty?

Of will the girl, tired of waiting, give the man up?

Will there be tragedy? Or will the last reel of the drama be played to the chimes of wedding bells?

Hollywood, dealer in love stories of all kinds, is eager to rush onto print with the details of synthetic romances among the motion-picture stars.

Strangely enough, it is equally zealous to keep real romances from the knowledge of the press.

It may be that Hollywood feels something of awe, encountering the real thing, the romance it can neither buy nor sell, the love story that is written by Life.

At any rate, Hollywood has been chary of letting news of the romance between Clark Gable and Carole Lombard seep into print. It has, grudgingly, admitted that Mr. and Mrs. Gable have separated, and that Clark has often escorted Miss Lombard here and there. But that is all.

It has given no hint of the heartaches that must exist deep below the surface of the story, the anguish, the yearning, the bitterness, and the tears.

This isn’t a springtime love affair, but it has poignancy and beauty for all that. Here are two people in the full splendid summer of their lives, with the sun of fame and fortune shining brightly on them—and autumn coming on apace.

And here is the wife, the charming, cultured, sophisticated Mrs. Rhea Gable, watching the two with what emotions no one knows.

What will autumn bring her? Restored serenity, or gray despair? Loneliness, or peace?

Perhaps if Carole and Clark had met in the springtime of their lives they would have been merely infatuated with each other. But it is not so now. They have experienced too much of life to trifle with anything so enduring as real love. They have suffered too much, learned too much, to take love lightly.

They have a lot in common, these two stars. They both enjoy informality. They like to be themselves. They welcome anything simple and natural which will give them fun. They like getting into old clothes and going to some out-of-the-way place. Also they like dressing up now and then and visiting some public pot.

You may see them at an amusement park, laughing like a couple of kids at nothing at all, trying to be as inconspicuous as possible. You may run across them eating in some obscure little hole in the wall, enjoying the music of a four-piece Mexican orchestra. You might see them at Carole’s home, playing bridge with friends. You might see them at the arena on fight nights, yelling with gusto “Sock him the kish-kish, Albie; he can’t take it there!”

Both have been unfortunate in their love affairs. Carole thought that life and all its problems had been solved for her when she first met William Powell. She was twenty-two, and, though he was sixteen years older, there was a gay spirited youthfulness about him that appealed to her intensely, that promised her eternal happiness. There was a lightness, a breeziness, an impish joyousness to him, a tenderness no words could adequately describe.

And yet their marriage ended in divorce.

Carole obtained the decree on the grounds of incompatibility. Powell put no obstacle in her way. He is still her friend. She is still his friend.

But it isn’t a major tragedy, when marriage deteriorates into mere friendship—a glimpse of each other now and then; a little smile at meeting; a handshake or pat on the back for old times’ sake; a civil “How are you” uttered in the same voice that once thrilled with “Oh, my dear, my dear!” ; a calm look in the yes that once reflected only ecstasy on the presence of the other?

Marriage, made out of love and brightness and joy and singing hope, stifling in misunderstandings, struggling in incompatibilities, yawned and died; and was not greatly mourned.

But it must have left a scar. It must have left a lasting doubt—“Is love like that?”

And there was a second romance that ended not less tragically.

Carole had begun to think better of love. She had met Russ Colombo, the handsome young man with the golden voice. She had become his greatest fan, then his worshiper. And he died. Accidently, cleaning his gun, he shot himself.

The death of Russ Colombo made Carole Lombard, Hollywood says, in its cocksure way. When she returned to the screen, after the long absence that followed his death, she was a better actress than she had ever been. She was actually a comedienne! Her comedy was of the highest type, that sort whose roots are planted in the deep, rich soil of sorrow.

Suffering and solitude had mellowed and softened her, shaped her character, enlarged her understanding and her sympathy.

They put her in “20th Century,” and gave her free rein for her talents. And even those critics who had said she was little more than a gorgeous clothes horse and a mildly funny foil for bigger stars now admitted she was one of the outstanding personalities of the screen.

Clark Gable was ripened through tragedy of another kind, the tragedy of futility and disappointment.

Life, that now denies him little, was more than niggardly to him in his youth. It have him hard work in various parts of the country. It made him a timekeeper, a lumberjack, a laborer in the oil fields of Oklahoma, an actor of sorts playing unsuitable roles in one-night stands with theatrical companies that never got anywhere.

He came to Hollywood when he was young and got little but rebuffs, an extra part once in a while, a day’s pay, a door slammed in his face. Nobody in the film capital cared if he lived or died.

He married a woman much older than himself, a woman who helped him immeasurably along the rocky road to stardom. She spent hours teaching him, and he spent hours training himself to be perfect in one role, in one scene.

Did he really love this woman, Josephine Dillon, Hollywood asks, and did she really love him? Was there more maternal than wifely feeling in her?

Clark was twenty-one when he married her. He was twenty-nine when she obtained her divorce. Mrs. Gable was in Los Angeles then. Clark was in New York. He had arrived in that city after a long tour of the south. He was playing in “Machinal,” and he had met Rhea Langham, a wealthy divorcee from Kentucky, whose brother was in the cast of the play.

Scarce had Josephine divorced him than Clark married Rhea Langham. Like Josephine, Rhea was much older than her husband. They came out west on their honeymoon. Clark was playing a part in “The Last Mile.” Hollywood gave him a little more recognition on this second visit. MGM gave him a screen test. Eventually he appeared with Norma Shearer in “A Free Soul.”

Mrs. Gable, who loves society, entertained lavishly, did all in her power to accompany her husband into the hectic life of Hollywood, and to keep pace with him as he walked through the glare of the light that plays on movie stars. Hollywood has a way of lionizing the star, and ignoring his family—especially if the family does not “belong.” Yet Mrs. Gable attained the “inner circle” in her own right.

And, for a time, all seemed as merry as a wedding bell.

Clark and Carole met in 1932 when they were selected to play in “No Man of Her Own.”

Both were married then; and apparently happily married. There wasn’t the faintest suspicion of any romantic attachment between the two, though they clowned together continually.

They were just having a lot of fun together, and everybody who watched them had fun with them. Either Clark or Carole always had some new gag, some new joke to spring. Where either was, there was bound to be spontaneity, laughter, honest enjoyment.

It was not until Jock Whitney’s “gag party,” on Feb. 7, 1936, that Carole and Clark took any serious interest in each other.

Powell had become just a friend by that time. Columbo was dead. Josephine Dillon was gone into obscurity. And Rhea Gable had left her husband and gone to New York.

She had left him once before, it was said, but later had come back to Hollywood. Everything had been well again for a time in the home of the Gables. And then everything was wrong again. Clark and his wife had definitely separated. There had been some attempts to effect a property settlement, it was said, but the terms of the settlement were in dispute.

The Whitney party was held at noon, and the guests were requested to appear in formal evening clothes. Carole had herself carried into the Whitney residence on a stretcher.

The guests rushed to her, horror-stricken, thinking she had been injured—and found her laughing at them.

The gag appealed to Gable. It attracted him to Carole more than anything else had done. And, somehow, Carole felt the attraction as much as he did.

The following week, on St. Valentine’s Day, she sent him the queerest valentine any man ever received.

It was nothing but a Model T Ford, dug up from a prehistoric burying ground, or enticed from a museum—a battered, shattered, tattered, and be-spattered wreck of an auto.

It was horribly ancient, and terribly vulgar, and exquisitely unattractive. It had rheumatism in all its joints. It exhibited every symptom of St. Vitus’ dance when it was in motion. Its glass was cracked, its fenders bent and gnarled and warped and torn and twisted into fantastic shapes. Its upholstery was moldy and shredded. It had been patched and repatched, and the naked springs stuck through it here and there. Its paint had flaked off in places.

It was the most disreputable car in all the modern world. But it was covered with painted hearts, and so it was a valentine, unique and precious.

He drove it over to Carole’s home, and insisted on taking her out immediately for a ride. Carole consented gladly, and the two went bumping, galumphing, limping, jerking, wheezing, and blowing out great clouds of odorous vapors, down the principal thoroughfares of Hollywood to the immaculate Trocadero.

That’s a long time ago—two years and more—a very long time for lovers to wait. Thus far, time has held no threat to their romance. But, if the years pile up, and the hope of their marrying pales, may bot their ardor and their passion languish and die?

Love never dies, says another old saw.

Many a super-epic in the films has preached the sermon of love’s eternity; and one of the first love stories ever written deals with the timelessness of a man’s affections. This is the story of Jacob who worked seven years for Laban, on the premise of winning his daughter Rachel. When the years were done Laban made a wedding feast. But the bride was not Rachel; she was Leah, Rachel’s older sister. Leah the tender-eyed, the cross-eyed. Jacob worked another week of years for the girl he loved.

Will Carole and Clark wait seven years if they must? And another seven thereafter if circumstances so compel them? Who can say?

Love never dies?

Stories in every newspaper every day indicate that love dies many deaths. Carole’s love for William Powell died. Clark’s love for Josephine died. His love for Rhea is dying, if it be not dead.

This tory has never been written before. It isn’t fully written now. Time is writing it. Time will furnish its climax and its end. It may be one of the deepest tragedies, one of the most poignant romances in Hollywood. The fans can only watch and wait, “with malice toward none; with charity for all” the principal characters.

How will the drama end? Will one of the lovers forsake the other? Will they both, someday, regard the cold ashes of their love, and sigh a little? Or will they wait patiently, chins up, brave smiles painted on their faces, never flagging in their romance?

True love never runs smooth? Perhaps it never does.